AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

Autonomy Among Thieves:

Template Course Design for Student and Faculty Success

Kathleen Huun, Indiana State University, Indiana

Lisa Hughes, Indiana State University, Indiana

Abstract

Responding to a student-expressed need for consistency among courses within the online

Baccalaureate Nursing Completion program at Midwestern University, an instructional designer

and nursing faculty member collaborated to build a course evaluation rubric, learning

management system template, and corresponding matrix to help support student learning and

retention as well as faculty autonomy and creativity. This effort carefully aligned the ADDIE

approach with Rogers’ (2003) diffusion of innovation theory through frequent, meaningful

communication with the nursing faculty and the interspersing of humor (thievery puns) to

invigorate and inspire adoption. Beginning with the design of a rubric based on Quality Matters

standards, the project evolved into a related template that demonstrated the application of the

rubric concepts while incorporating faculty-developed content. Change architects then created a

complementary matrix that outlined required, adaptable, or addable template elements to

maintain consistency and sustain faculty autonomy. Survey results show promising

improvements in both student perceptions of online course navigation and content and faculty

perceptions of reduced workload and continued autonomy.

Keywords: Online Baccalaureate Nursing Completion programs; Diffusion of Innovation

Theory; Quality Matters; Instructional Design; Change Architecture: Student Retention

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

INTRODUCTION

Through continual process improvement (CPI), the Baccalaureate Nursing Completion (BNC)

program at Midwestern University has critically evaluated the structure of online courses within

their nursing tracks in order to bolster accreditation and assure the highest quality distance

education to enhance both student and faculty success. The BNC program offers an online RN to

BS as well as the only fully online LPN to BS nursing track in the United States. While the RN

to BS track has seen steady enrollment, the LPN to BS track has continued to grow exponentially

since its inception. This quick expansion of a unique and in-demand program has warranted

careful attention to and assessment of feedback from both students and faculty perspectives to

ensure continued improvement as the department continues to be the pioneer for this specific

component of baccalaureate completion. Likewise, course and program enhancements serve to

benefit the traditional RN to BS completion track.

Student feedback gathered from standard end-of-course surveys (Electronic Student Instructional

Reports, or eSIRs) from individuals enrolled in the BNC program over the course of three years

revealed that the structure and delivery of course materials was especially relevant to student

success and satisfaction. Regular complaints included inconsistent file delivery and layout

between courses within the same online track, unclear assignments, inability to plan ahead,

illogical navigation, and technical issues within the BNC’s sole course delivery learning

management system (LMS), Blackboard. Likewise, faculty felt bombarded with student course

navigation problems as well as technical concerns at the onset of each semester. Thus students

and faculty alike identified significant problems with course design and delivery.

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

Consequently, to some degree, these issues resulted from a lack of detailed expectations to

consistently evaluate online course design at the University and departmental levels. Although

the Center for Instructional Research and Technology (CIRT) did have an evaluation form used

for general online course design, it was not thorough and did not address issues specific to online

nursing education. Thus, with the goal of student success and faculty ease and autonomy on the

forefront, a nursing distance faculty and an instructional designer (referred as change architects)

combined their efforts and expertise to address these substantial problems of practice in the

online education of nurses.

In order to maintain the highest of standards and support a component of the University’s

strategic plan which sought to “strengthen programs of distinction and promise” (Author, 2012),

the change architects adopted the Quality Matters (QM) Rubric, an evidenced-based, national

standard by which to assess the quality of online course design via inter-institutional, peer review

processes. With its roots firmly planted in a FIPSE grant from the U.S. Department of Education,

QM started as an initiative of MarylandOnline and has grown into a research-based, professional

standard for online course design (MarylandOnline, 2006). To date the QM Rubric has become

the most commonly employed set of standards for online course design at the college/university

level (MarylandOnline, 2006), thus a tangible solution for the BNC course design problem.

Armed with a proven standard and through applied research, the change architects initiated a

transformation of online course design and delivery based on best practice. While an immense

task, the change architects turned to ADDIE, an instructional design approach, Rogers’ (2003)

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

diffusion of innovations theory, humor, and thievery to guide the way through three distinct,

related phases of development based on QM standards: an evaluation rubric, an LMS template,

and a complementary matrix.

FRAMEWORK AND THEORETICAL BASE

ADDIE, a mnemonic for the processes of analysis, design, development, implementation, and

evaluation, constitutes a simplified instructional design framework. The analysis phase begins

with the identification of a problem of practice or need. This is followed with the design and

development of the innovation, defined as “an idea, practice, or object that is perceived as new

by an individual or other unit of adoption” (Rogers 2003, p. 12), to address the need. Putting the

innovation to the test with the target audience(s) occurs during the implementation phase.

Although evaluation customarily falls to the rear, it is actually ongoing throughout the process

through formative and eventually summative evaluation.

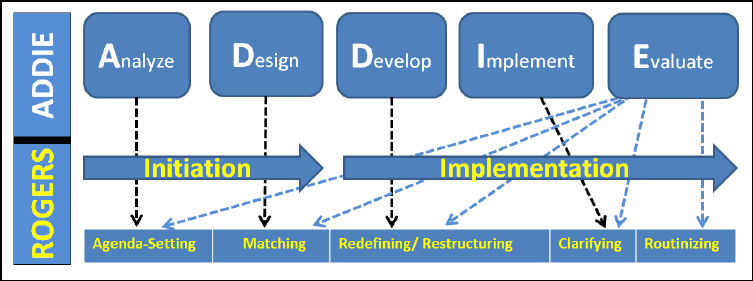

While ADDIE served the prescription for product development, Rogers’ diffusion of innovation

theory thoroughly addressed the relationship of the innovation within the context of the recipient

user/organization. The first two of Rogers’ (2003) five stages, agenda setting and matching,

constitute the initiation phase and align with analysis and design within the ADDIE framework.

Agenda setting is the observation of a need, while matching is fitting the perceived need with an

innovation. Implementation encompasses Rogers’ final three stages of redefining/restructuring,

which is molding the innovation to fit the organizational need, clarifying or situating the

innovation and defining it more clearly, and routinizing, where the innovation becomes second

nature and loses its novel identity. These implementation stages align with ADDIE’s develop,

implement, and evaluate phases. This auspicious alignment, the ADDIE framework and Rogers’

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

(2003) five stages of the innovation process in organizations (see Figure 1) create a partnered

approach to the development of the innovation (ADDIE) with attention to intertwined sublayers

within the process (Rogers, 2003).

Figure 1. Overlay of ADDIE framework and Rogers’ (2003) five stages of the inovation process

in organizations.

As evidenced in Figure 1, the process of evaluation is continuous and should readily infuse each

stage of Rogers’ (2003) innovation process. Such diffusion involves “(1) an innovation (2)

communicated through certain channels (3) over time (4) among the members of a social system”

(Rogers, 2003, p. 11). The BNC innovation, as a result, would become threefold (rubric,

template, matrix) as it was communicated via the change architects through face-to-face focus

sessions, presentations, and test runs over several semesters among the stakeholders, the BNC

nursing faculty. Although this alignment and method implies a smooth, linear process,

acceptance and engagement with an advantageous innovation can be difficult (Rogers, 2003).

Thus, attributes of the innovation become very relevant to faculty “buy in.” Rogers (2003)

identifies these attributes as relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trialability, and

observability. These attributes are referenced throughout the stages of development to facilitate

approval, ownership, and adoption from the faculty.

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

ANALYSIS OF STUDENT FEEDBACK

Per department standard, end-of-course surveys are posted at the completion of each semester for

student responses. The BNC department uses the generic eSIR surveys which are intended to

“identify areas of strength and/or areas for improvement, provide information on new teaching

methods or techniques used in class, [and] provide feedback from students about their courses”

(Educational Testing Service, 2012). Although these surveys reflect student opinion on the

course content and instructor, a few questions allude to course design and delivery. Specifically

these questions are as follows:

The instructor's explanation of course requirements

The instructor's preparedness for this course

The instructor's organization of course material into logical components

Responses to these targeted questions and the open-ended inquiries regarding overall student

perception of the course caught the attention of the BNC faculty and exposed some significant

problems pertaining to course design and delivery that were hindering student success to some

degree. Student comments and concerns revealed the following problems of practice:

Inconsistent file delivery between courses within the same program

Unclear assignments (including due dates and instructions)

Inability to plan ahead

Illogical navigation

Technical issues within Blackboard

Design and Development

Rubric and Rationale

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

Through analysis (ADDIE) of student feedback and agenda-setting (Rogers, 2003), the change

architects identified the glaring problem of practice—“lack of continuity” from course to course

within the BNC tracks—as an inhibitor of student success. The matching stage (Rogers, 2003)

enabled the change architects to fit a solution to the perceived need, while the design phase

(ADDIE) resulted in the creation of the first innovation, an evaluation rubric for BNC online

courses.

This problem of practice resulted from a void of detailed expectations to evaluate online course

design in a consistent manner at the University and departmental levels. Thus, the program chair

challenged a nursing distance faculty to create a rubric (innovation) to provide a more detailed

outline of course expectations and sound design. What evolved was a multiple-page, thorough,

inclusive rubric that incorporated mandatory and recommended course elements as well as

separate clinical elements (not all BNC courses had a clinical component). The rubric would

become Part 1 of the innovation.

Early in the process, an instructional designer joined the innovation team to align the extensive

BNC rubric with QM rubric to add a course design standard and quality to the vision of the

project. In doing so, the emphasis was on the following QM standards: course overview and

introduction, learner interaction and engagement, course technology, and learner support and

accessibility. Beyond this, the underlying principles of QM also offered guidance as the change

architects set forth to present the innovation to the BNC faculty. Following the QM principles,

the innovation was and is to be a continuous process of improvement that is centered on sound

research and best practice, quality, and student learning. Likewise, the diffusion process is to be

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

collegial and collaborative (MarylandOnline, 2010).

Template: An Intermix of Ideas and Indispensables

With the developed rubric and quality-control overlay, the additional need for a governing

template was apparent through ongoing evaluation and a return to agenda setting and matching

(Rogers, 2003) in conjunction with design and development (ADDIE) for Part 2 of the

innovation, the LMS template.

In accordance with research performed by Sloan-Consortium (Sloan-C), the desire for exemplary

design warranted an even stronger, visual cornerstone than the specially-designed rubric supplied

(Burgess et al., 2008). Thus, in order for faculty to envision the rubric content as it might apply

to their own online courses, an instructional designer generated the BNC Blackboard template to

ensure a coherent, consistent, effective online course design (Burgess, Barth, & Mersereau,

2008).

To address identified student concerns, the goal of the template was to furnish a basic structure

that enabled faculty to maintain consistency across courses throughout the BNC tracks while

abating student confusion and increasing student learning. These efforts sought to “lighten the

load on working memory, allowing for more efficient processing of information and improved

retention of content” (Bristol & Zerwekh 2009, p. 247). Ultimately, this would also reduce the

faculty workload while simultaneously enhancing their creativity and exploration. Although a

lofty venture for a project that started with a fundamental rubric, these noble goals are consistent

with Sloan-C’s findings regarding the outcome of and support for template usage and

necessitated additional design and development (Burgess et al., 2008).

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

Part of this design and development (ADDIE) required significant input from the directly

involved potential adopters, as “there must be support, input, and buy-in from the faculty” and

faculty feedback is essential “because of their valuable work experience and unique

understanding of the needs of the students” (Bristol & Zerwekh, 2011, p. 195, 157). Therefore,

the change architects sought and invited faculty input and feedback as a means of actively

engaging them in redefining/restructuring (Rogers, 2003) to develop their sense of ownership

and ease the eventual implementation process.

This participation allowed faculty to closely assess various attributes of the innovation. Faculty,

therefore, were able to consider compatibility, “the degree to which an innovation is perceived as

being consistent with the existing values, past experiences, and needs of potential adopters”

(Rogers, 2003, p. 15). Faculty support and embrace student success, the quality of their online

program, reduction in menial workload, and continual process improvement, all values fostered

by the innovation and discovered and reinforced through the feedback process. Based on relative

advantage, “the degree to which an innovation is perceived as better than the idea it supersedes”

(Rogers, 2003, p. 15), faculty became aware of the opportunity to enhance and bridge their

existing courses in a manner that serviced students and faculty alike.

The creation of the template involved interprofessional collaboration, reliant on shared goals and

individual expertise. Thus, to enhance the template design and display the intellectual creativity

and diverse talents of the faculty, the designers added several elements from BNC faculty

courses into the template as exemplars of ideas into action. The redefining/restructuring stage

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

(Rogers, 2003) also highlighted another attribute of the innovation, observability. Faculty

members were able to see the quality course design choices made by others and incorporate the

concepts into their own course creations. According to Rogers (2003), “The easier it is for

individuals to see the results of an innovation, the more likely they are to adopt” (p.16); therefore

the redefining/restructuring phase was essential for eventual adoption.

This synthesis process involved all faculty members inviting the instructional designer into their

courses to search for their exemplary content items. All items chosen had faculty approval. Thus,

the template design required continuous dialogue between faculty and the instructional designer

by way of email, phone, or face-to-face communication. As illustrated by Choa, Saj, and

Hamilton (2010), these types of conversations can create a “sense of team solidarity because they

. . . [help] create a shared understanding and vision” (p. 114). Furthermore, “interpersonal

channels are more effective in forming and changing attitudes toward a new idea” (Rogers, 2003,

p. 36). Thus, the purposeful engagement of faculty in the development process of the template

through intentional communication also enhanced the possible adoption of the innovation.

Design determinants.

Essentially, the design of the template was based on alignment to the BNC rubric with a steadfast

focus on organization and ease of navigation. As Bristol and Zerwekh (2011) assert, “An

important part of the Web-based classroom is organization. Too much on-screen confusion often

leads to a poor learning experience” (p. 136). Likewise, having clear navigation buttons “adds a

structure that will help novice users navigate the materials, and seasoned users will know where

to look for information” (O’Neil, Fisher, & Newbold, 2009, p. 90). This need for organization

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

clearly ties into consistency, a core goal of the BNC project, which provides predictability of

navigational features from course to course.

A case in point is the University of Colorado’s School of Nursing (SON) online courses. In 2006

all courses were required to use a standardized template that mandated the icons and syllabus

structure. In their explanation of the SON template system, Lee, Holloway, and Field (2006)

revealed:

Though you may think that these types of standards stifle imagination and creativity for courses,

students in particular find it very refreshing to go to every SON online course and immediately

be familiar with the lay of the land for every course. Not having to navigate or learn a different

look and feel based on the individual preferences of instructors proves to be a convenient,

timesaving mechanism -- in other terms, immediacy perception -- in delivering our courses. Both

students and faculty immediately know where and how to find the information and tools they

need; they can hit the ground running. (p. 144)

This kind of immediacy and efficiency was a primary focus of the BNC template design and

supported the goal of consistency across courses.

Through the template design, the change architects also sought to align the resulting template to

the QM Rubric. In doing so, like with the BNC evaluation rubric design, the emphasis was on the

course structure and components of the template needed to follow the associated QM standards.

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

However, as the change architects have added more template content through the diffusion

process, faculty have acquired greater access to additional, optional resources to help them better

address a wide array of QM standards, including those related to course objectives, assessments,

and instructional materials. Because individual faculty members continue to value autonomy and

heavily protect their own course materials, and in support of the QM concepts of collegial and

collaborative interchanges, the change architects chose to avoid mandating the broader details of

course design during the diffusion process until a later point in time via individual consultations

focusing on holistic course design rather than the application of the basic template.

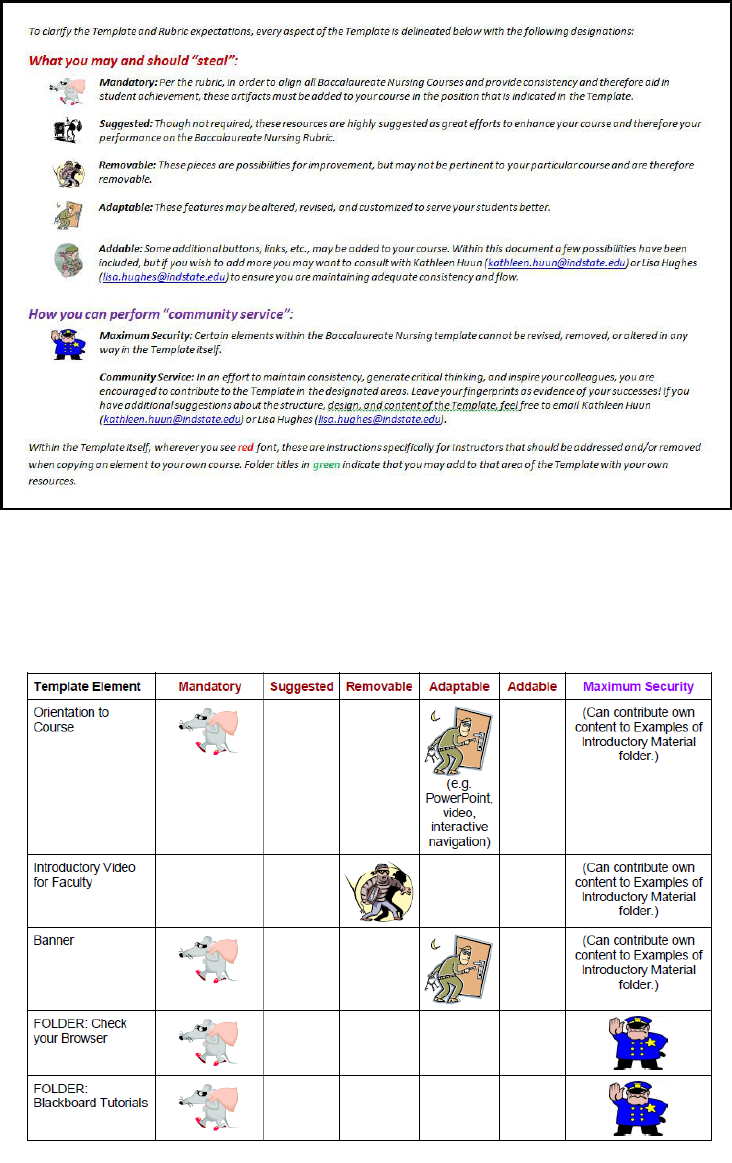

Matrix and mirth.

Through ongoing evaluation during development, it became apparent that the template, which

provided the concrete foundation for all BNC courses, did not in itself offer flexibility, critical

when upholding and utilizing faculty subject matter, instructional expertise, and autonomy.

Thus, once again, the change architects fell back on agenda setting and matching (Rogers, 2003)

as well as design and development (ADDIE) for Part 3 of the innovation, the matrix. This

blueprint cleverly clarified what elements within the template were mandatory, suggested,

removable, adaptable, and addable. Correlated to a theme and icons of thievery to encourage the

“stealing” of template elements (see Figures 2 and 3), the matrix lightheartedly defines template

content instructors may and should steal in an effort to induce faculty buy-in through emphasized

autonomy as well as good-natured humor.

Lei, Cohen, and Russler (2010) contend that an appropriate use of humor may provide cognitive,

social, and psychological benefits to the recipient learner. Key cognitive benefits to the use of

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

humor include an increase in motivation, captured interest and attention, inspired creativity,

heightened problem-solving, and enhanced comprehension of course (rubric, template, matrix)

information. Likewise, humor in content delivery and presentation provide the following social

advantages: reduced fear, development of a sense of trust, and creation of a positive and relaxed

climate for learning. Two psychological benefits, alleviation of anxiety and reversal of

negatively inured feelings (Lei et al., 2010), are crucial to the success of the innovation.

To encourage buy-in and increase learning, therefore, a police icon alerts faculty to template

items that are under maximum security and are not to be tampered. Since faculty have full access

to the template in order to copy all desired materials and add additional models of template

application to the example folders, the officer of the law protects those items that are off-limits

and not editable by anyone other than the change architects. These “untouchables” must remain

in their original form for accuracy and consistency as they create a repository of police-protected

items of the most recent BNC documents, policies, evaluations, and forms that should be

included within courses. These latter specifics of the matrix development highlight redefining

/restructuring (Rogers, 2003).

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

Figure 2. Definitions of template designations and usability as aligned to a humorous, image-

specific thief within the matrix.

Figure 3. Thief images and their association to template content as identified on the matrix.

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

Another advantage of the online storehouse is that it remains continually updated so faculty can

do one-stop-shop lifting for the most up-to-date information and resources. To alert faculty of

template updates, the change architects generate emailed course announcements within the LMS.

The matrix organization mirrors that of the template and the rubric to assist with application and

clarify expectations. While consistency was critical to the overarching goal of the continued

design, ensuring faculty buy-in and authority was also key, hence the need for a correlating

matrix that motivated, inspired, and humored in a collegial and collaborative fashion.

Implementation

Faculty engagement: Finding the funny bone.

Due to the nature of the BNC rubric, template, and matrix project, the change architects were

given some assurance of adoption as implementation was mandatory for all BNC faculty and

based on an authority decision “where the adopting individual has no influence in the innovation-

decision” (Rogers, 2003, p. 29) albeit the faculty did have considerable input in the design and

content of the Blackboard template portion of the innovation, ensuring ample compatibility with

the adopters’ values and perceived needs. Despite the mandatory requirement to implement the

BNC Blackboard template, the change architects believed that the attributes of their innovation

as perceived by the recipient faculty would itself promote its rate of adoption. Engaging

faculty through this mandatory process of clarification (Rogers, 2003) and implementation

(ADDIE) required a light and enjoyable approach. Thus, the change architects employed an

attempt at humor. It has been shown that if a “humorous message has elements that enhance

students’ ability to process such as being related to the course content or makes the content

relevant, then students will be more likely to process the instructional message and learning will

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

be enhanced” (Wanzer, Frymier, & Irwin, 2010, p. 7). The change architects assumed that the

faculty, now in the learner role, would also enjoy and relate to the content of the innovation if

humor was interwoven.

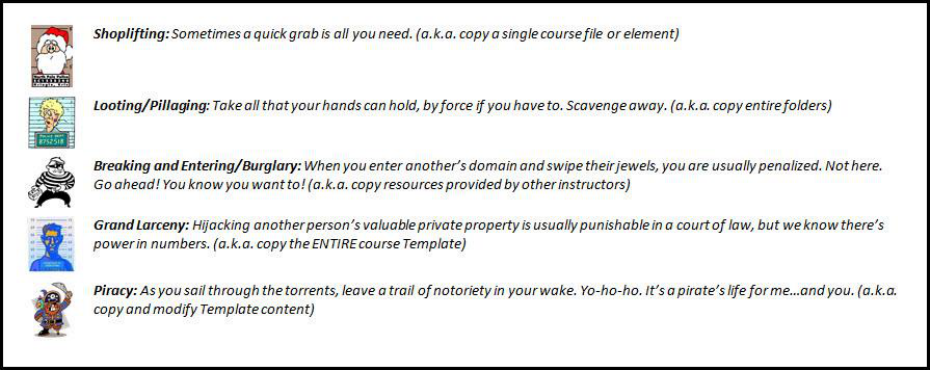

To facilitate faculty’s acceptance and understanding of copying template content, both

mandatory and suggested, into their own courses, the idea of thievery evolved and was

encouraged. As a result, the change architects developed several icons and definitions,

representative of the crimes, for the band of thieves (faculty). These (supported) criminal

offenses correlated to the amount and type of content “stolen” from the template (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Criminal offenses as they relate to “stealing” template content.

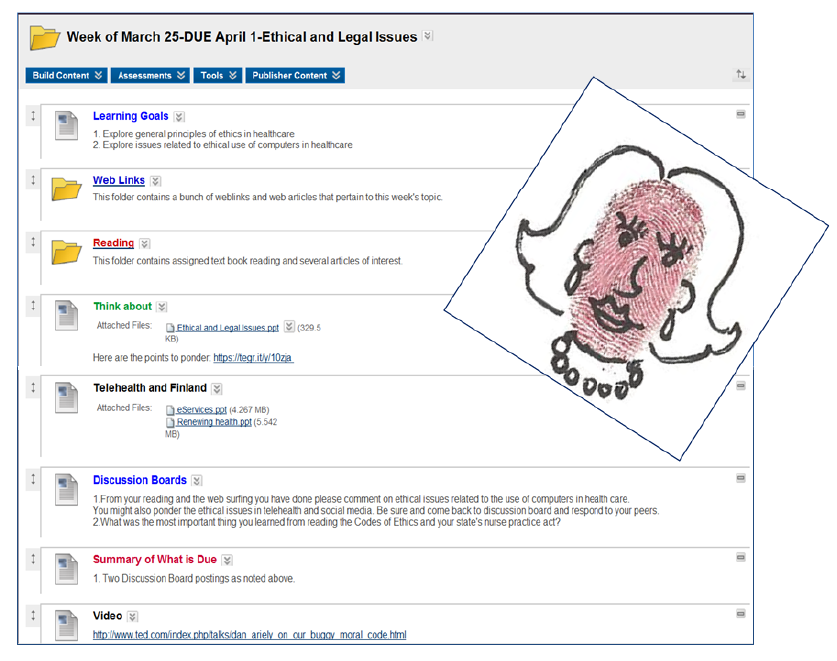

Along with this frivolity promoting the pillaging of template content is encouragement for

faculty to perform community service time as payment for their criminal actions. The template

instructions ask faculty to leave their mark (fingerprint) on the template by adding example items

of their own exemplary, creative, or innovative work for others to see and use or draw ideas.

Essentially, the template encourages the thieves to leave some forensic evidence. Figure 5 offers

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

an example of faculty contribution that acts as evidence of the application of the template

guidelines and resources.

Figure 5. Faculty forensic evidence: Example of student paper, layout, content, rubric and

student support elements. (Courtesy Betsy Frank RN PhD ANEF)

Implementation and impediments.

The diffusion of innovation was an important process to allow “the faculty member and the

instructional designer . . . to become a productive team [given] . . . enough time to establish

expectations up front . . . [and] allowing themselves to move at a pace that gives them room to

listen to feedback and to reflect” (Choa, Saj, & Hamilton, 2010, p. 114). Through small group

presentations and one-on-one interaction with the instructional designer, implementation

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

(ADDIE) ensued as the change architects gradually introduced and immersed faculty into the

innovation. For clarifying (Rogers, 2003), the change architects created sandbox/development

sites for some instructors so they could “play” with the template, via trialability, and assess the

complexity before transferring content to their actual course. Via appraisal of the template

attributes, the change architects assisted faculty members in developing an awareness for the

compatibility of the innovation to their previous and familiar modes of course delivery.

Despite the flexibility and support built within the template, a great concern regarding faculty

autonomy remained, due to the difficulty of establishing an understanding of the difference

between course design and course delivery. According to QM, course design entails the thought

and planning that an individual faculty member integrates into a course, while course delivery is

the actual instruction of the course and employment of the course design. Thus, the latter

concept, course delivery, is where the primary faculty autonomy lies. Once faculty understood

this distinction through intentional and varied interactions with the change architects, that

knowledge significantly reduced barriers to the template adoption.

RESULTS

No innovation comes without consequences (Rogers, 2003). As a result, the change architects

have instituted post-semester surveys for students and faculty alike for the past four semesters

(fall 2012, spring 2013, summer 2013, and fall 2013) to assess direct and indirect impacts of the

template application. Since change architects just unveiled the template in fall 2012, results are

somewhat limited but promising. Student surveys were distributed within each online nursing

course, while faculty surveys were distributed within the Template; both populations’

participation varied and therefore was not inclusion of all learners and instructors. Initial results

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

show a somewhat favorable outcome and suggest a continuation of the template application may

have an additional positive effect on student attitudes and perceptions regarding user-friendliness

of navigation, although student perceptions of continuity have not increased. While the faculty

was initially concerned about the mandated structure of the template, survey results indicate an

increase in awareness, adoption, and acceptance as well as a reduction in workload, thus

fulfilling the primary objectives of the innovation.

Student Survey Results

The majority (90-94%) of BNC students who participated in the surveys are female, and

according to survey results, nearly half of all students who completed the survey each semester

are ages 31-45. The rest of the population are nearly equally split between ages 23-30 and 46 or

older, with a single individual falling within the 18-22 range early in the diffusion process. 86-

94% of survey participants each semester indicated their GPA was 3.0 or higher.

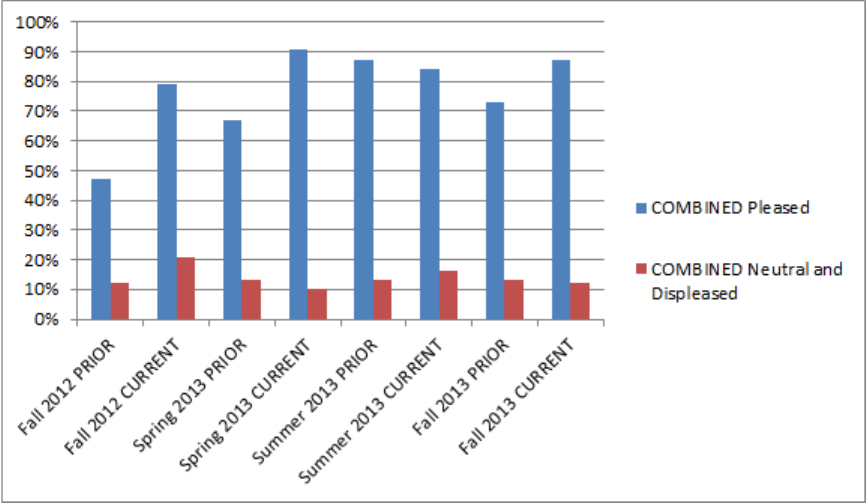

Survey responses reveal that most students were generally already pleased with the overall

online nursing course structures prior to the semester the survey was completed, a direct

contradiction to eSIR results collected in preceding semesters, which indicated a pronounced

need for consistent navigation among courses. However, after fall 2012 students could have

already been exposed to courses that had applied the template. The innovation was initially to be

adopted by faculty in fall 2012, thus an immediate overall positive response to perceptions

regarding previous course navigation. While comparative results of student perceptions of

overall course structure prior to the semester of survey completion to the current semester in

which the survey was completed are mixed and do not indicate growth nor decline from one

semester to the next, a trend is becoming evident in that more and more students are somewhat

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

pleased, pleased, or very pleased with the overall course design, with fewer ambivalent or

displeased responses (as indicated in Figure 6). This suggests that as the template application

becomes more ingrained in the culture of the online nursing courses, as more faculty are trained

and work with instructional designers on their course to apply the template in meaningful ways,

the effect is improved student perceptions in the overall course navigation.

Figure 6. Comparison of student responses to overall course structure prior to the semester and

during the semester (current) of survey completion.

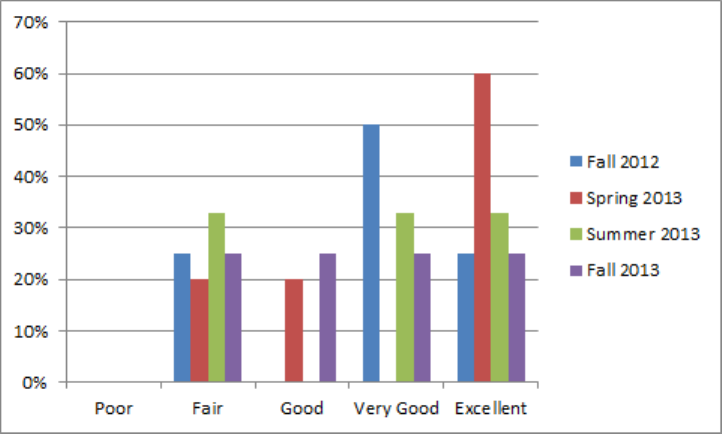

Specifically, student perceptions of the course navigation’s user-friendliness have drastically

increased from the first semester of adoption to the current semester. Although recent trends

suggest a slight decline in student satisfaction with user-friendliness, the first semester of the

template pilot only 51% of the student population agreed or strongly agreed that the navigation

was user-friendly, whereas in recent semesters 93%, 88%, and 87% of the students felt that the

course was user-friendly (see Figure 7).

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

Figure 7. Student responses to user-friendliness of course navigation and structure.

One area that continues to challenge online nursing courses at the University is that of continuity.

While the majority of students are indeed satisfied with the continuity between courses, there has

been no significant increase in that number, with 83% of students initially satisfied with the

continuity between courses at the onset of the template application and just 84% of students

currently satisfied with continuity. While the satisfaction rate for continuity is acceptable, growth

was the aim, and as a primary goal of the template project, this area must still be addressed

through faculty training, consultations, and full adoption of the template.

Faculty Survey Results

Faculty survey participants throughout the four semesters polled primarily consisted of

instructors with three or more years of online teaching experience, and all but one of the 18 total

respondents had taken at least one online course as a student prior to teaching their course(s).

Although no faculty respondents had online teaching certification the first semester of template

adoption (fall 2012), by fall 2013 nearly all faculty respondents had acquired certification

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Fall 2012 Spring

2013

Summer

2013

Fall 2013

COMBINED Agreement

Neutral

COMBINED Disagreement

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

through the University’s Online Instructor Certificate Course (OICC), Quality Matters’ Applying

the QM Rubric course, and/or the Quality Matters’ Peer Reviewer Certification course. Each of

these certifications was a direct result of initiatives of the template adoption process. Although

designed for faculty of all disciplines, the OICC encompasses not only the QM Rubric standards,

through which the design of the template was revised and confirmed, but also a general template

design that is based on the original BNC Blackboard template now distributed campus wide for

voluntary adoption. The results of the faculty survey therefore indicate that one positive impact

of the template adoption was an increase in interest and knowledge in online teaching and

learning.

Each semester, most faculty respondents noted that prior to actually implementing the template

they were already “very pleased,” “pleased,” or “somewhat pleased” with the concept, although

two respondents total did feel “somewhat displeased” and one “very displeased” with the idea of

the template when it was first proposed. After adopting and implementing the template,

encouraging results show that faculty are even more impressed with the template design and

application, with 67-80% of respondents each semester being “very pleased” after

implementation versus 20-33% prior to application. Additionally, 75-100% of faculty members

believe the template design is “logical.” This suggests that the template design, diffusion process,

and instructional design support have expedited and affirmed the adoption process by validating

its relative advantage, compatibility, and complexity (Rogers, 2003).

Additionally, faculty perceptions positively convey a reduction in course development workload

as a direct result of the template application, with 66-100% of respondents each semester noting

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

a reduction in workload, thus fulfilling a primary goal of the template project. Admittedly, this

number has decreased since the onset of the pilot program in fall 2012, suggesting additional

support and clarification may be necessary to further assist faculty in continuing to apply the

template design, which is frequently updated to better reflect recent research and best practices.

Despite the slight increase in workload (which is still less than before the template diffusion,

according to survey results), 75-100% of respondents each semester acknowledge that the initial

workload required to design and develop their courses is actually offset by the reduction in

workload later in the semester due to fewer assignments turned in late (20-50% perceived it to be

better than before the previous semester) and fewer navigation questions (33-80% perceived it to

be better) than prior to the template application.

Whenever a course element is mandated, a concern of faculty is often independence or academic

freedom, thus autonomy became essential for a successful diffusion. When surveyed, faculty

acknowledged not only the value of the mandatory items within the template, with 100% of

faculty respondents agreeing to their usefulness, but also the retention of their autonomy, with

the majority of respondents indicating it was “good,” “very good,” or “excellent” (see Figure 8).

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

Figure 8. Faculty response to autonomy afforded by the template application process.

Not all faculty survey results are quite as promising, however. Although slight fluctuation in

responses has occurred, faculty perceptions of the template’s user-friendliness has not changed

from fall 2012 to fall 2013, with 75% “strongly agreeing” and 25% “agreeing” that the template

design and usage is manageable and appealing. While still a fair result, increasing user-

friendliness is a continued goal as the template is frequently updated.

Another secondary goal of the template was to encourage faculty to attempt new instructional

and assessment strategies to further engage students in the learning process via resources and

techniques provided within the template; however, fewer than half of the faculty respondents

have utilized a new technique as a result of the template. Although it is likely that routinizing

(Rogers, 2003) has played a role in a reduction in such participation, more faculty development

in this area is needed to better support the goals of the template. Similarly, fewer than half of

faculty respondents have contributed to the template by posting their own examples or resources.

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

Although not a requirement, faculty contributions were promoted through the concept of leaving

a “fingerprint” in return for the “stolen goods” swiped from the template. Faculty buy-in or

ownership through contributions was encouraged to enhance communication channels and

homophily, or shared values and participant characteristics (Rogers, 2003), within the template.

While the Matrix was created to designate optional and required materials within the structure of

the template, its use has dwindled since the onset of the template application process. Originally,

100% of faculty respondents utilized the Matrix to assist with their course design based on the

template; however, in recent semesters half or fewer than half of respondents have used it, likely

a result of routinizing (Rogers, 2003). Certainly, more emphasis on its practical use and relative

advantage is needed to promote this tool.

CONCLUSION

Through the application of the basic ADDIE framework and Rogers’ (2003) complimentary

diffusion of innovations theory, the change architects developed a three-part innovation (rubric,

template, and matrix) to support student learning and retention as well as faculty autonomy and

creativity. Via continuous evaluation, the framework and theory were used in a cyclical process

as each new element of the innovation was developed. The end result was a tool (innovation) that

lends structure yet adaptability to a department wide strategy to enhance learning and best utilize

faculty productivity. As the innovation is a “living” tool, through continuous process

improvement with a basis of “best practice,” it will continue to develop as warranted by its use.

Overall, based on survey results and various conversations with stakeholders, it is clear that

students are particularly impressed with the reduction in extraneous effort previously needed to

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

navigate through a variety of course designs. Likewise, faculty members are encouraged by the

resulting decrease in workload after just a few semesters of applying the consistent design.

Although some faculty are still concerned with particular elements of the template they wish to

see removed or added to better facilitate their own course visions, most accept the need for

consistency across courses and acknowledge the decrease in student emails complaining about

navigational issues. Additionally, instructors appreciate remaining up-to-date with best practice

methodologies and are continually engaged in refining their courses since the template continues

to be updated and faculty are notified via LMS announcements and emails.

These results affirm the successful fulfillment of the BNC project goals – to increase consistency

and reduce faculty workload – but they also speak to other unexpected (though still welcomed)

consequences or needs. Through the template diffusion process, the demand for current research

and best practice became apparent, hence the continual development of the template.

Furthermore, adoption is a perpetual process that requires reinforcement and careful

consideration of current and changing faculty and student needs.

Ultimately, the design and development of the BNC rubric, template, and matrix project did not

end with its initial development, but rather through continued evaluation and adoption practices,

it has become a living project that continues to grow with the evolution of the students, faculty,

department, and University. For example, while the QM Rubric was a foundational piece for the

project from the onset, the verbalized desire for an authoritative and definitive evaluation tool

necessitated official QM-certified courses. Consequently, all BNC faculty enrolled in the

“Applying the QM Rubric” workshop. Using a known “expert” entity (QM) rather than merely

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

the change architects, who may have been too homophilic (Rogers, 2003) in some regards to

inspire continued adoption of the template and new course design requirements, added a much-

needed layer of depth and credibility. Promoting faculty to enroll and complete this course

facilitated their understanding of learning objectives and assessment and measurement of quality

course design, filling in the gaps of the original template design, which initially focused solely

on navigation and structure. As a direct and desirable consequence, several faculty members

continued on to complete subsequent courses offered by QM. In addition, the next phase of

diffusion involves faculty completing “in house” peer reviews of courses and ultimately seeking

actual QM certification for courses. The success accomplished through this project has indeed

inspired other departments to adopt similar template innovations and participate in the QM pilot

to further enhance their programs and increase faculty and student success.

Additional areas of concern have also been identified through the continual evaluation process.

Survey results, for example, indicate student perception of instructor presence within online

BNC courses has not significantly changed since the template application process began.

Although not a central goal of the template, instructor presence has been somewhat encouraged

through the template content via tips, techniques, and resource links. Despite the prevalence of

materials, instructor presence has not increased with the template application, therefore

additional diffusion strategies are needed to better address this concern.

The change architects continue to seek ways to enhance online learning with the BNC online

tracks and acknowledge the need for additional studies to confirm not just the perceived

acceptance of the template application, but perhaps more importantly, the actual impact on

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

performance resulting from the project. This research needs to address both the student and the

faculty perspective.

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

References

Author. (2012). The pathway to success. Online presentation. http://irt2._/ir/assets/splan/

stratplan.pdf.

Bristol, T. J., & Zerwekh, J. (2011). Essentials of e-learning for nurse educators. Philadelphia,

PA: F. A. Davis.

Burgess, V., Barth, K., and Mersereau, C. (2008). Quality online instruction -- a template for

consistent and effective online course design. The Sloan Consortium. Retrieved from

http://sloanconsortium.org/effective_practices/quality-online-instruction-%E2%80%93-

template-consistent-and-effective-online-course-des.

Chao, I. T., Saj, T., & Hamilton, D. (2010). Using collaborative course development to achieve

online course quality standards. International Review of Research in Open and Distance

Learning, 11(3), 106-126.

Educational Testing Service. (2012). Interpreting eSIR [PDF document].

Lee, H., Holloway, N., & Field, L. (2006). Teaching online pathophysiology: The University of

Colorado Health Science Center School of Nursing. In J. M. Novotny, & R. H. Davis

(Eds.), Distance education in nursing (pp. 139-150). New York: Springer.

Lei, S. A., Cohen, J. L., & Russler, K. M. (2010). Humor on learning in the college classroom:

Evaluating benefits and drawbacks from instructors' perspectives. Journal of

Instructional Psychology, 37(4), 326-331.

MarylandOnline. (2006). Quality Matters. Retrieved from http://www.qmprogram.org/.

O’Neil, C. A., Fisher, C. A., & Newbold, S. K. (2009). Developing online learning environments

in nursing education (2nd ed.). New York: Springer.

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). New York: Free Press.

AUTONOMY AMONG THIEVES

Wanzer, M.B., Frymier, A.B., & Irwin, J. (2010). An explanation of the relationship between

instructional humor and student learning: Instructional humor processing theory.

Communication Education, 59(1), 1-18.