Financial reporting developments

A comprehensive guide

Revenue from

contracts with

customers

(ASC 606)

September 2023

To our clients and other friends

Accounting Standards Codification (ASC or Codification) 606 provides accounting guidance for all revenue

arising from contracts with customers to provide goods or services (unless the contracts are in the scope

of other US GAAP topics, such as those for leases). The standard, which is largely converged with the

revenue recognition guidance in IFRS, also provides a model for the measurement and recognition of

gains and losses on the sale of certain nonfinancial assets, such as property and equipment, including

real estate (see our Financial reporting developments (FRD) publication, Gains and losses from the

derecognition of nonfinancial assets (ASC 610-20)).

This FRD publication summarizes the US GAAP standard, including all amendments issued to date, as well

as the guidance in ASC 340-40 on accounting for costs an entity incurs to obtain and fulfill a contract to

provide goods and services to customers (see section 9.3). It addresses topics on which the members of

the Transition Resource Group for Revenue Recognition (TRG) reached general agreement and discusses

our views on certain topics, including those that are based on our understanding of the views of the

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB or Board) and/or its staff and the staff of the Securities and

Exchange Commission (SEC).

The FASB’s post-implementation review (PIR) of the standard is ongoing and includes evaluating the

standard’s effectiveness and identifying areas for improvement. As part of this process, the Board directed

its staff to perform research, outreach and education on certain key topics, including principal versus

agent considerations, consideration payable to a customer, licensing and variable consideration. At a

Board meeting in September 2022, the Board discussed the staff’s research and asked its staff to continue

to monitor the costs and benefits of ASC 606. We encourage readers to monitor developments.

Our Technical Lines, Effects of inflation and rising interest rates on financial reporting and Accounting

and reporting considerations for the war in Ukraine, discuss the potential accounting and financial

reporting implications of inflation, rising interest rates, the war in Ukraine, the sanctions on Russia and

any related effects. Revenue recognition areas that may be affected include variable consideration,

contract modifications and terminations, a measure of progress based on expected costs, collectibility

and any extended payment terms, changes to selling prices, and loss contracts.

Our industry-specific publications (listed in Appendix F) highlight key aspects of applying the standard.

We encourage preparers and users of financial statements to read this publication and the industry

supplements carefully and consider the effects of the standard.

We expect to periodically update our guidance. The views that we express in this publication may

continue evolving as application issues are identified for new and emerging transactions and discussed

among stakeholders. Appendix A summarizes significant changes since the previous edition.

September 2023

Financial reporting developments Revenue from contracts with customers (ASC 606) | i

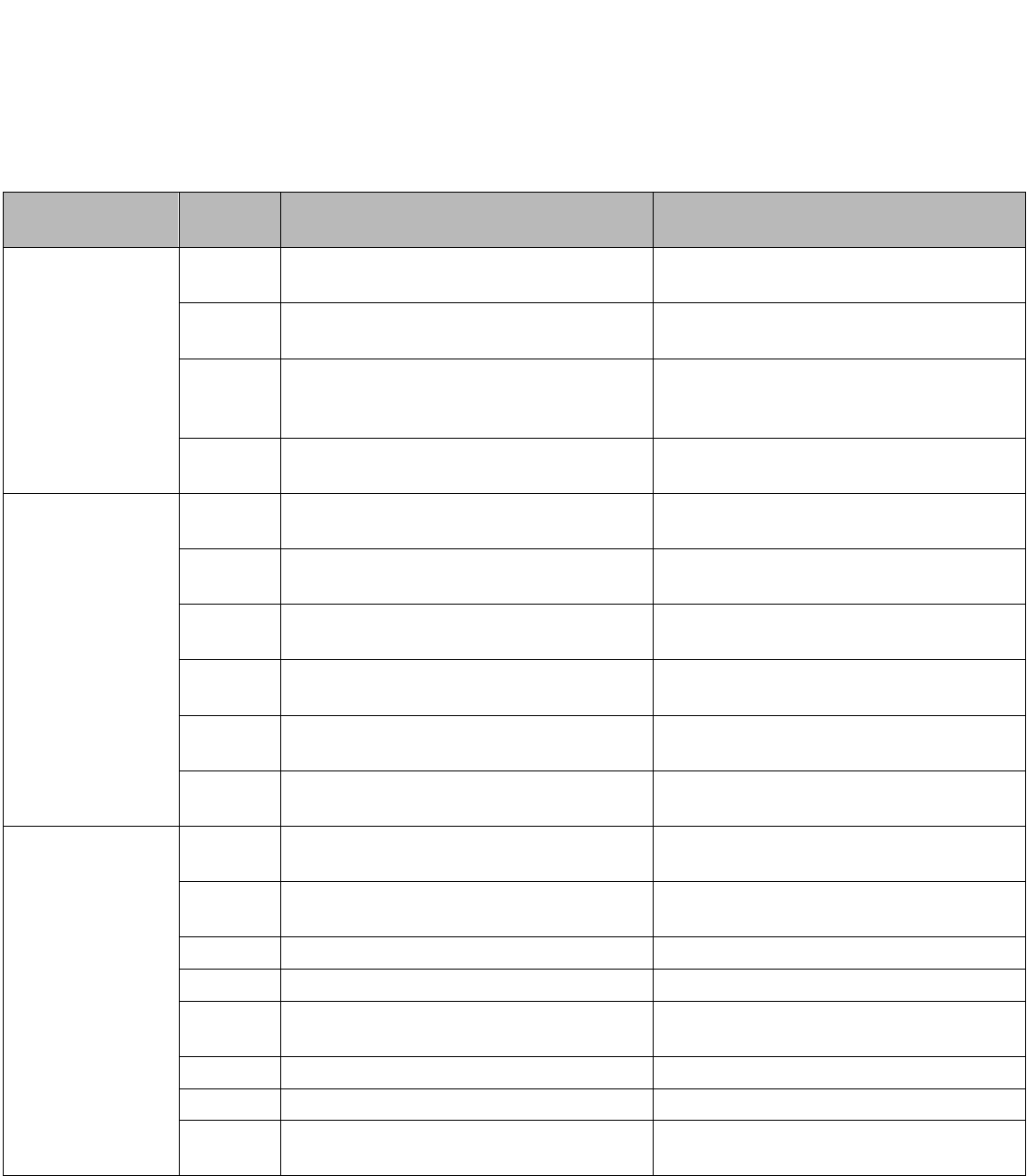

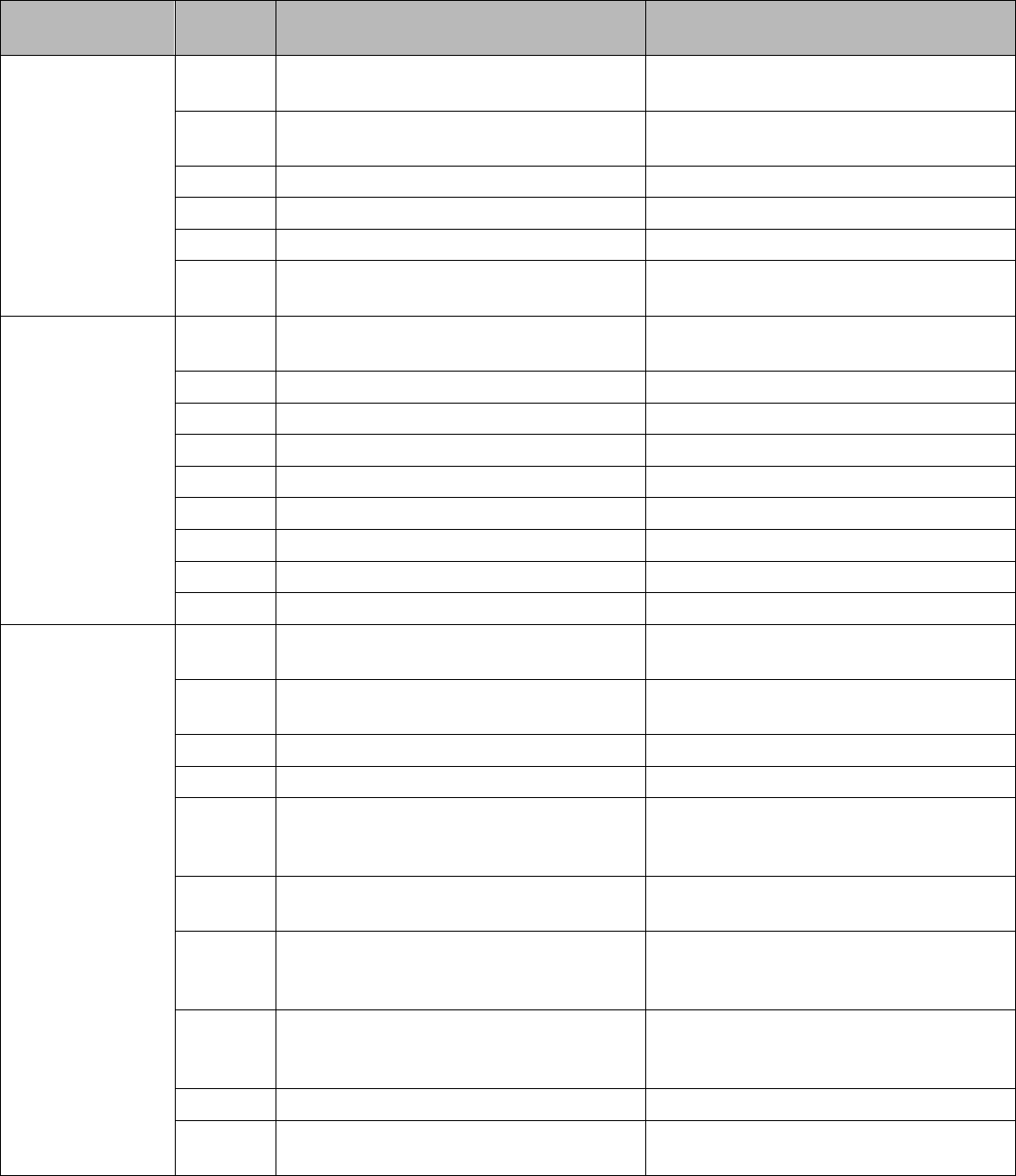

Contents

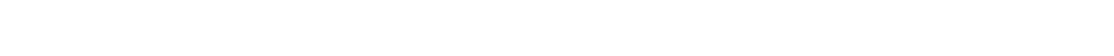

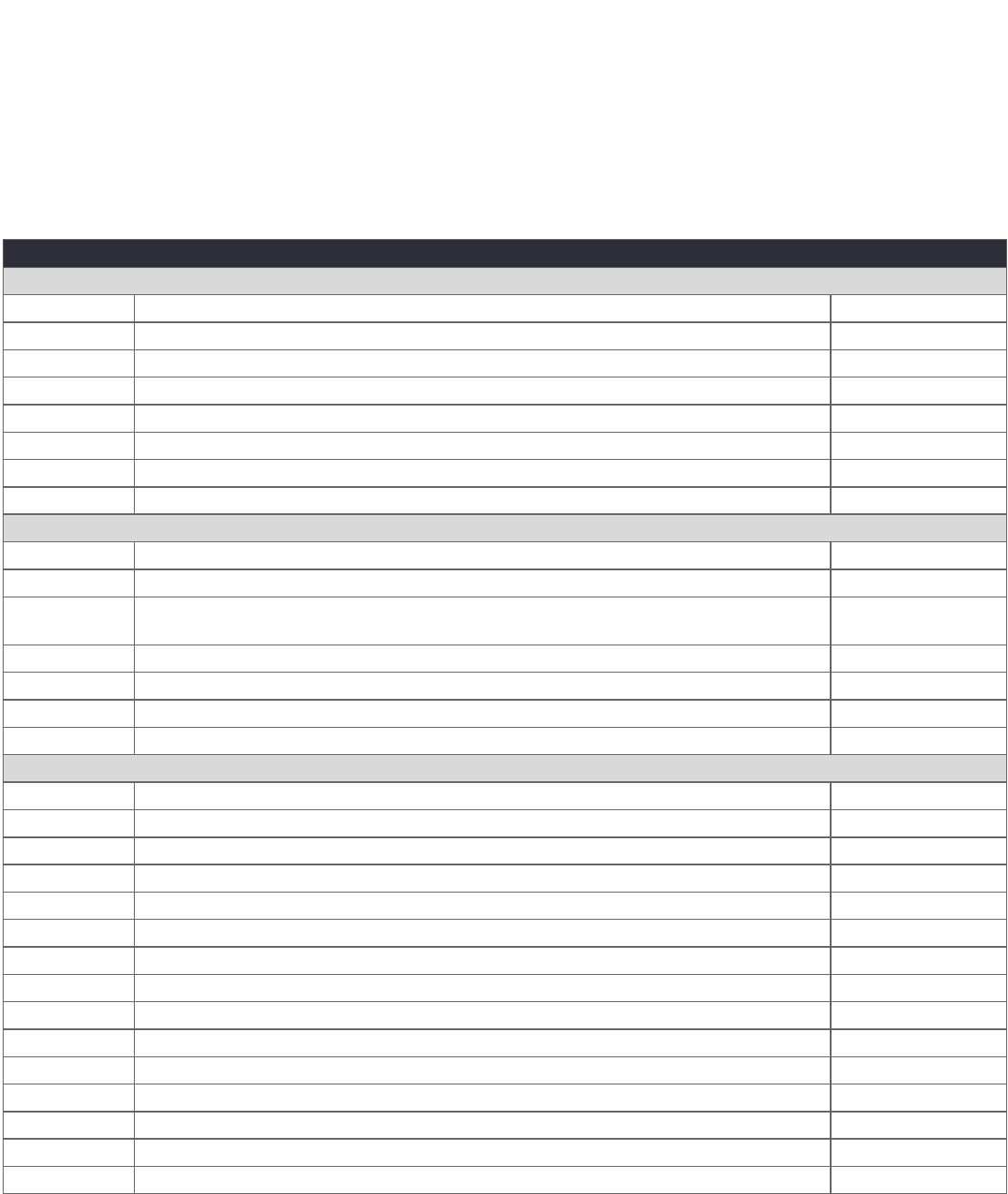

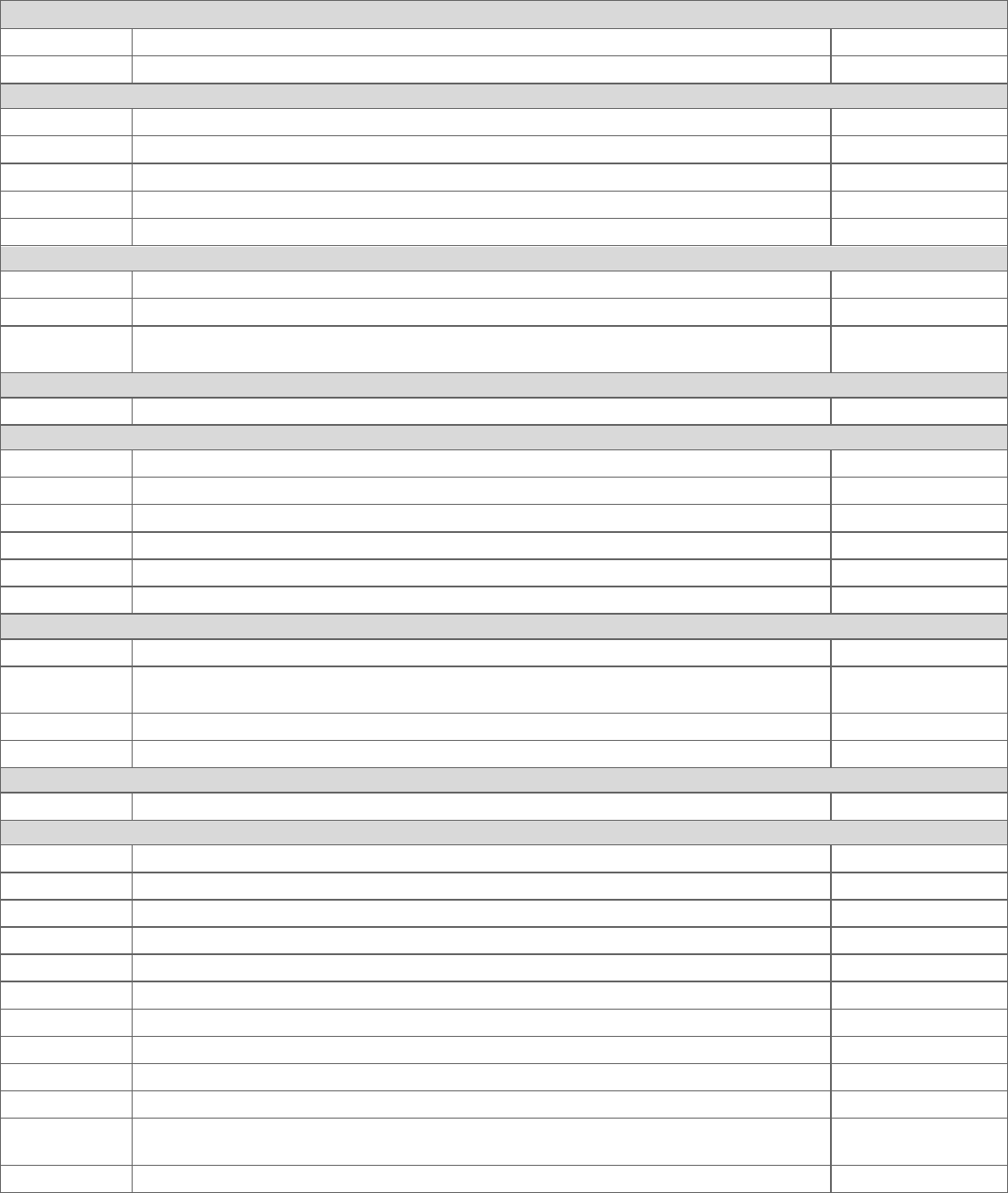

1 Overview ................................................................................................................... 1

1.1 Overview ............................................................................................................................... 1

1.1.1 Core principle of the standard ........................................................................................ 2

1.1.2 Executive summary of the five-step revenue model (updated September 2022) .............. 2

1.1.3 Other recognition and measurement topics (updated September 2022) ........................... 7

2 Scope ........................................................................................................................ 9

2.1 Other scope considerations (updated September 2023)......................................................... 10

2.1.1 Nonmonetary exchanges ............................................................................................. 10

2.2 Definition of a customer ....................................................................................................... 11

2.3 Collaborative arrangements ................................................................................................. 12

2.4 Interaction with other guidance (updated September 2022) ................................................... 14

3 Identify the contract with the customer..................................................................... 21

3.1 Attributes of a contract ........................................................................................................ 22

3.1.1 Parties have approved the contract and are committed to perform their

respective obligations .................................................................................................. 26

3.1.2 Each party’s rights regarding the goods or services to be transferred can be identified ... 26

3.1.3 Payment terms can be identified for the goods or services to be transferred .................. 26

3.1.4 Commercial substance ................................................................................................ 27

3.1.5 Collectibility ................................................................................................................ 27

3.2 Contract enforceability and termination clauses (updated September 2023) ........................... 34

3.3 Combining contracts ............................................................................................................ 41

3.3.1 Portfolio approach practical expedient ......................................................................... 42

3.4 Contract modifications (updated September 2023) ............................................................... 43

3.4.1 Contract modification represents a separate contract ................................................... 51

3.4.2 Contract modification is not a separate contract ........................................................... 52

3.5 Arrangements that do not meet the definition of a contract under the standard ...................... 59

4 Identify the performance obligations in the contract .................................................. 63

4.1 Identifying the promised goods and services in the contract (updated September 2022) ...... 64

4.1.1 Promised goods or services that are immaterial in the context of a contract ................... 74

4.1.2 Shipping and handling activities (updated September 2023) .......................................... 75

4.2 Determining when promises are performance obligations..................................................... 77

4.2.1 Determination of distinct ............................................................................................. 79

4.2.1.1 Capable of being distinct .................................................................................... 80

4.2.1.2 Distinct within the context of the contract ........................................................... 81

4.2.2 Series of distinct goods or services that are substantially the same and

that have the same pattern of transfer ......................................................................... 91

4.2.3 Examples of identifying performance obligations .......................................................... 98

4.3 Promised goods and services that are not distinct................................................................ 107

4.4 Principal versus agent considerations (updated September 2022) ........................................ 107

4.4.1 Identifying the specified good or service (updated September 2022) ........................... 110

4.4.2 Control of the specified good or service (updated September 2022) ............................ 113

4.4.2.1 Principal indicators (updated September 2022)................................................. 116

Contents

Financial reporting developments Revenue from contracts with customers (ASC 606) | ii

4.4.3 Recognizing revenue as a principal or agent ............................................................... 120

4.4.4 Examples (updated September 2022) ........................................................................ 122

4.5 Consignment arrangements ............................................................................................... 133

4.6 Customer options for additional goods or services ............................................................... 133

4.7 Sale of products with a right of return ................................................................................. 148

5 Determine the transaction price.............................................................................. 150

5.1 Presentation of sales (and other similar) taxes (updated September 2022) ........................... 152

5.2 Variable consideration ....................................................................................................... 153

5.2.1 Forms of variable consideration ................................................................................. 154

5.2.1.1 Implicit price concessions ................................................................................. 158

5.2.2 Estimating variable consideration .............................................................................. 161

5.2.3 Constraining estimates of variable consideration ........................................................ 166

5.2.4 Reassessment of variable consideration ..................................................................... 175

5.3 Refund liabilities ................................................................................................................ 176

5.4 Rights of return ................................................................................................................. 176

5.5 Significant financing component ......................................................................................... 181

5.5.1 Examples .................................................................................................................. 186

5.5.2 Financial statement presentation of financing component ............................................... 194

5.6 Noncash consideration ....................................................................................................... 195

5.7 Consideration paid or payable to a customer (updated September 2022) ............................. 199

5.7.1 Forms of consideration paid or payable to a customer ................................................. 202

5.7.2 Classification and measurement of consideration paid or payable to a

customer (updated September 2023) ........................................................................ 203

5.7.3 Timing of recognition of consideration paid or payable to a customer

(updated September 2023) ....................................................................................... 207

5.8 Nonrefundable up-front fees .............................................................................................. 211

5.9 Changes in the transaction price ......................................................................................... 213

6 Allocate the transaction price to the performance obligations .................................. 214

6.1 Determining standalone selling prices (updated September 2023) ........................................ 215

6.1.1 Factors to consider when estimating the standalone selling price ................................. 217

6.1.2 Possible estimation approaches ................................................................................. 218

6.1.3 Updating estimated standalone selling prices (updated September 2023) .................... 222

6.1.4 Additional considerations for determining the standalone selling price ......................... 222

6.1.5 Measurement of options that are separate performance obligations ............................ 225

6.2 Applying the relative standalone selling price method ............................................................. 229

6.3 Allocating variable consideration ........................................................................................ 232

6.4 Allocating a discount .......................................................................................................... 240

6.5 Changes in transaction price after contract inception (updated September 2023) ................. 244

6.6 Allocation of transaction price to elements outside the scope of the standard ....................... 247

7 Satisfaction of performance obligations .................................................................. 249

7.1 Performance obligations satisfied over time (updated September 2023) .............................. 250

7.1.1 Customer simultaneously receives and consumes benefits as the entity performs ............ 252

7.1.2 Customer controls the asset as it is created or enhanced............................................. 255

7.1.3 Asset with no alternative use and right to payment ..................................................... 256

7.1.4 Measuring progress (updated September 2022) ......................................................... 269

7.1.4.1 Output methods ............................................................................................... 273

7.1.4.2 Input methods.................................................................................................. 275

Contents

Financial reporting developments Revenue from contracts with customers (ASC 606) | iii

7.1.4.3 Examples (updated September 2022) ............................................................... 278

7.2 Control transferred at a point in time (updated September 2022) ......................................... 283

7.2.1 Customer acceptance ................................................................................................ 288

7.3 Repurchase agreements .................................................................................................... 291

7.3.1 Forward or call option held by the entity ..................................................................... 292

7.3.2 Put option held by the customer ................................................................................ 295

7.3.3 Sales with residual value guarantees .......................................................................... 298

7.4 Consignment arrangements ............................................................................................... 299

7.5 Bill-and-hold arrangements ................................................................................................ 300

7.6 Recognizing revenue for licenses of intellectual property ..................................................... 303

7.7 Recognizing revenue when a right of return exists ............................................................... 303

7.8 Recognizing revenue for customer options for additional goods and services ........................ 304

7.9 Breakage and prepayments for future goods or services (updated September 2023) ............ 304

8 Licenses of intellectual property ............................................................................. 309

8.1 Identifying performance obligations in a licensing arrangement ............................................ 310

8.1.1 Licenses of intellectual property that are distinct ........................................................ 310

8.1.2 Licenses of intellectual property that are not distinct .................................................. 313

8.1.3 Contractual restrictions ............................................................................................. 314

8.1.4 Guarantees to defend or maintain a patent ................................................................. 317

8.2 Determining the nature of the entity’s promise in granting a license ..................................... 321

8.2.1 Functional intellectual property.................................................................................. 321

8.2.2 Symbolic intellectual property .................................................................................... 325

8.2.3 Evaluating functional versus symbolic intellectual property ......................................... 327

8.2.4 Applying the licenses guidance to a bundled performance obligation that

includes a license of intellectual property ................................................................... 329

8.3 Transfer of control of licensed intellectual property ............................................................. 331

8.3.1 Right to access.......................................................................................................... 332

8.3.2 Right to use .............................................................................................................. 333

8.3.3 Use and benefit requirement...................................................................................... 333

8.4 License renewals ............................................................................................................... 334

8.5 Sales- or usage-based royalties on licenses of intellectual property

(updated September 2023) ................................................................................................ 336

9 Other measurement and recognition topics ................................................................... 351

9.1 Warranties ........................................................................................................................ 351

9.1.1 Determining whether a warranty is a service- or assurance-type warranty ................... 351

9.1.2 Service-type warranties ............................................................................................. 355

9.1.3 Assurance-type warranties ........................................................................................ 356

9.1.4 Contracts that contain both assurance- and service-type warranties ............................ 357

9.2 Loss contracts ................................................................................................................... 359

9.3 Contract costs ................................................................................................................... 360

9.3.1 Costs to obtain a contract (updated September 2022) ................................................ 361

9.3.2 Costs to fulfill a contract (updated September 2022) .................................................. 368

9.3.3 Amortization of capitalized contract costs .................................................................. 378

9.3.4 Impairment of capitalized contract costs .................................................................... 386

Contents

Financial reporting developments Revenue from contracts with customers (ASC 606) | iv

10 Presentation and disclosure (updated September 2022) .......................................... 389

10.1 Presentation requirements for contract assets and contract liabilities

(updated September 2022) ................................................................................................ 390

10.2 Presentation requirements for revenue from contracts with customers

(updated September 2022) ................................................................................................ 399

10.3 Other presentation considerations ...................................................................................... 401

10.3.1 Regulation S-X presentation requirements ................................................................. 402

10.4 Annual disclosure requirements .......................................................................................... 402

10.5 Disclosures for public entities ............................................................................................. 403

10.5.1 Contracts with customers .......................................................................................... 405

10.5.1.1 Disaggregation of revenue ............................................................................... 405

10.5.1.2 Contract balances ............................................................................................ 409

10.5.1.3 Performance obligations .................................................................................. 411

10.5.2 Significant judgments ................................................................................................ 418

10.5.2.1 Determining the timing of satisfaction of performance obligations ..................... 419

10.5.2.2 Determining the transaction price and the amounts allocated to

performance obligations ................................................................................... 420

10.5.3 Assets recognized for the costs to obtain or fulfill a contract ....................................... 420

10.5.4 Practical expedients .................................................................................................. 421

10.6 Disclosures for nonpublic entities ........................................................................................ 422

10.6.1 Contracts with customers .......................................................................................... 423

10.6.1.1 Disaggregation of revenue ............................................................................... 423

10.6.1.2 Contract balances ............................................................................................ 425

10.6.1.3 Performance obligations .................................................................................. 426

10.6.2 Significant judgments ................................................................................................ 428

10.6.2.1 Determining the timing of satisfaction of performance obligations ..................... 429

10.6.2.2 Determining the transaction price and the amounts allocated to

performance obligations ................................................................................... 429

10.6.3 Assets recognized for the costs to obtain or fulfill a contract ....................................... 430

10.6.4 Practical expedients .................................................................................................. 431

10.7 Interim disclosure requirements (updated September 2022) ................................................ 432

A Summary of important changes ............................................................................... A-1

B Index of ASC references used in this publication ....................................................... B-1

C Guidance abbreviations used in this publication ........................................................ C-1

D List of examples included in ASC 606 and ASC 340-40, and references in

this publication ....................................................................................................... D-1

E TRG discussions and references in this publication .................................................... E-1

F Industry publications ............................................................................................... F-1

G Glossary ................................................................................................................. G-1

H Summary of differences from IFRS .......................................................................... H-1

Contents

Financial reporting developments Revenue from contracts with customers (ASC 606) | v

Notice to readers:

This publication includes excerpts from and references to the Financial Accounting Standards Board

(FASB or Board) Accounting Standards Codification (Codification or ASC). The Codification uses a

hierarchy that includes Topics, Subtopics, Sections and Paragraphs. Each Topic includes an Overall

Subtopic that generally includes pervasive guidance for the Topic and additional Subtopics, as needed,

with incremental or unique guidance. Each Subtopic includes Sections that in turn include numbered

Paragraphs. Thus, a Codification reference includes the Topic (XXX), Subtopic (YY), Section (ZZ) and

Paragraph (PP).

Throughout this publication references to guidance in the Codification are shown using these reference

numbers. References are also made to certain pre-Codification standards (and specific sections or

paragraphs of pre-Codification standards) in situations in which the content being discussed is excluded

from the Codification.

This publication has been carefully prepared, but it necessarily contains information in summary form

and is therefore intended for general guidance only; it is not intended to be a substitute for detailed

research or the exercise of professional judgment. The information presented in this publication should

not be construed as legal, tax, accounting, or any other professional advice or service. Ernst & Young LLP

can accept no responsibility for loss occasioned to any person acting or refraining from action as a result

of any material in this publication. You should consult with Ernst & Young LLP or other professional

advisors familiar with your particular factual situation for advice concerning specific audit, tax or other

matters before making any decisions.

Portions of FASB publications reprinted with permission. Copyright Financial Accounting Standards Board, 801 Main Avenue,

P.O. Box 5116, Norwalk, CT 06856-5116, USA. Portions of AICPA Statements of Position, Technical Practice Aids and other AICPA

publications reprinted with permission. Copyright American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, 1345 Avenue of the Americas,

27

th

Floor, New York, NY 10105, USA. Copies of complete documents are available from the FASB and the AICPA.

Financial reporting developments Revenue from contracts with customers (ASC 606) | 1

1 Overview

1.1 Overview

The revenue recognition standard

1

provides accounting guidance for all revenue arising from contracts with

customers and affects all entities that enter into contracts to provide goods or services to their customers

(unless the contracts are in the scope of other US GAAP requirements, such as those for leases). The FASB

included more than 60 examples in the standard to illustrate how an entity might apply the guidance. We list

them in Appendix D to this publication and provide references to where certain examples are included in

this publication. The standard also refers to guidance in ASC 340-40 for the accounting for costs an entity

incurs to obtain and fulfill a contract to provide goods and services to customers (see section 9.3) and

provides a model for the measurement and recognition of gains and losses on the sale of certain nonfinancial

assets, such as property and equipment, including real estate (see our FRD, Gains and losses from the

derecognition of nonfinancial assets (ASC 610-20)).

The TRG, which was formed to help determine whether more guidance was needed to address implementation

questions and to educate constituents, included financial statement preparers, auditors and other users from

a variety of industries, countries, and public and private entities. TRG members’ views are non-authoritative,

but entities should consider these views as they apply the standard. The SEC’s former Chief Accountant

encouraged entities to consult with the Office of the Chief Accountant (OCA) if they are considering

applying the guidance in a way that is different from what TRG members generally agreed on.

2

We have

incorporated our summaries of topics on which TRG members generally agreed throughout this publication

(also see Appendix E for a listing of all TRG discussions and where they are discussed in this publication).

The FASB staff has compiled publicly available TRG memos and other educational resources previously issued

on the implementation of ASC 606 into a document called Revenue Recognition Implementation Q&As

(FASB staff Q&As). The staff’s objective in compiling this material, which is organized by subject matter

(e.g., step of the revenue model), was to make the available educational resources easier to navigate and

not to issue any new implementation guidance. We refer to the Q&As throughout this publication.

We also continue to monitor discussions by the IFRS Interpretations Committee (IFRS IC) on the application

of IFRS 15 (the revenue recognition standard issued by the International Accounting Standards Board

(IASB) in May 2014, which was largely converged with ASC 606)

3

because we believe that decisions made

by the IFRS IC about the application of that standard may support the same interpretation of ASC 606.

Therefore, we refer to certain IFRS IC discussions throughout this publication. Also see Appendix H for a

summary of significant differences between IFRS 15 and ASC 606.

As part of the FASB’s PIR of ASC 606, the FASB staff performed research, outreach and education on

certain key topics, including principal versus agent considerations, consideration payable to a customer,

licensing and variable consideration. In September 2022, the Board discussed the staff’s research and

asked the staff to continue to monitor the costs and benefits of ASC 606. We encourage readers to

monitor developments.

4

1

ASC 606, Revenue from Contracts with Customers (created by Accounting Standards Update (ASU) 2014-09). Throughout this

publication, when we refer to the FASB’s standard, we mean ASC 606, as amended, unless otherwise noted.

2

Remarks by Wesley R. Bricker, SEC Office of the Chief Accountant, 5 May 2016.

3

For more information on the effect of IFRS 15 for IFRS preparers, refer to our revenue chapter in International GAAP® available

in EY Atlas.

4

Refer to the Post-Implementation Review Projects page on the FASB website.

1 Overview

Financial reporting developments Revenue from contracts with customers (ASC 606) | 2

We also continue to monitor comment letters issued by the SEC staff on how registrants are applying the

revenue guidance and summarize certain of these comments throughout this publication. However, the

frequency of comments on revenue recognition peaked when registrants were adopting ASC 606 and

has continued to decline.

1.1.1 Core principle of the standard

The standard describes the principles an entity must apply to measure and recognize revenue and the

related cash flows. The core principle, as stated below, is that an entity recognizes revenue at an amount

that reflects the consideration to which the entity expects to be entitled in exchange for transferring

goods or services to a customer:

Excerpt from Accounting Standards Codification

Revenue from Contracts with Customers — Overall

Objectives

606-10-10-1

The objective of the guidance in this Topic is to establish the principles that an entity shall apply to

report useful information to users of financial statements about the nature, amount, timing, and

uncertainty of revenue and cash flows arising from a contract with a customer.

Meeting the Objective

606-10-10-2

To meet the objective in paragraph 606-10-10-1, the core principle of the guidance in this Topic is that

an entity shall recognize revenue to depict the transfer of promised goods or services to customers in

an amount that reflects the consideration to which the entity expects to be entitled in exchange for

those goods or services.

606-10-10-3

An entity shall consider the terms of the contract and all relevant facts and circumstances when

applying this guidance. An entity shall apply this guidance, including the use of any practical

expedients, consistently to contracts with similar characteristics and in similar circumstances.

Entities need to exercise judgment when considering the terms of the contract(s) and all of the facts and

circumstances, including implied contract terms. Entities have to apply the requirements of the standard

consistently to contracts with similar characteristics and in similar circumstances.

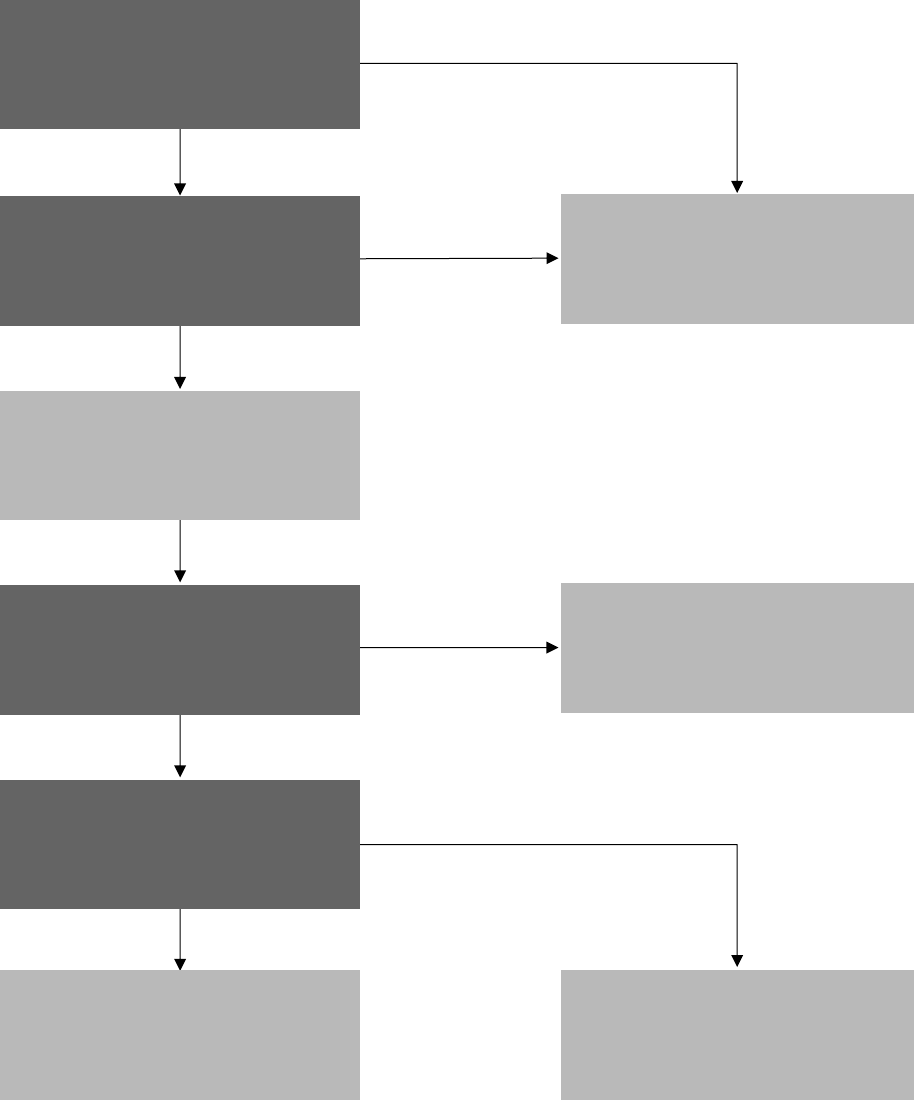

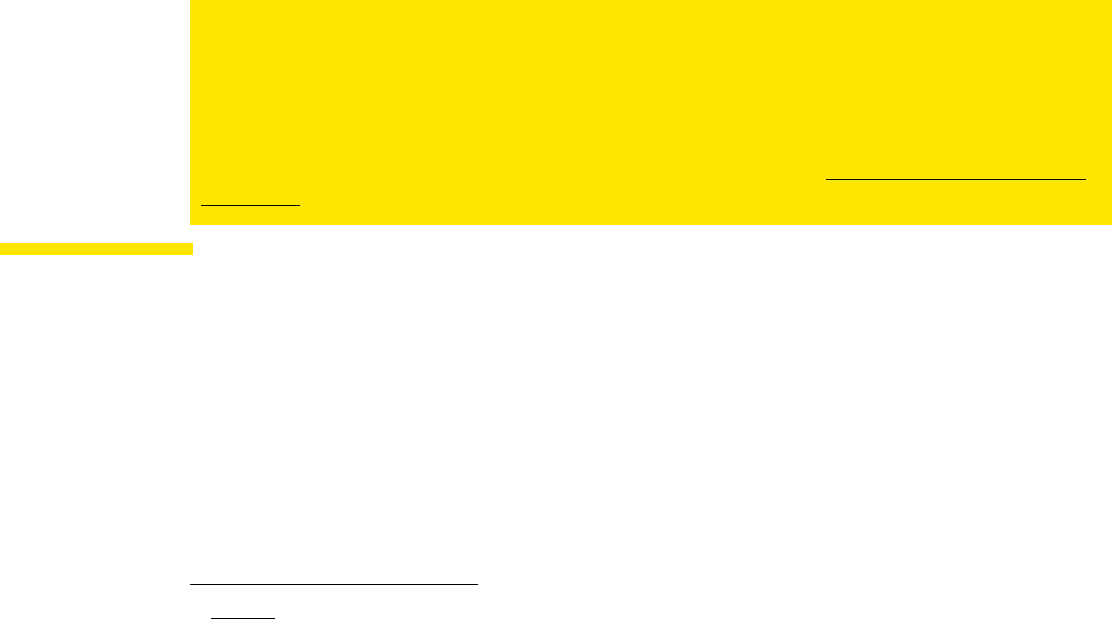

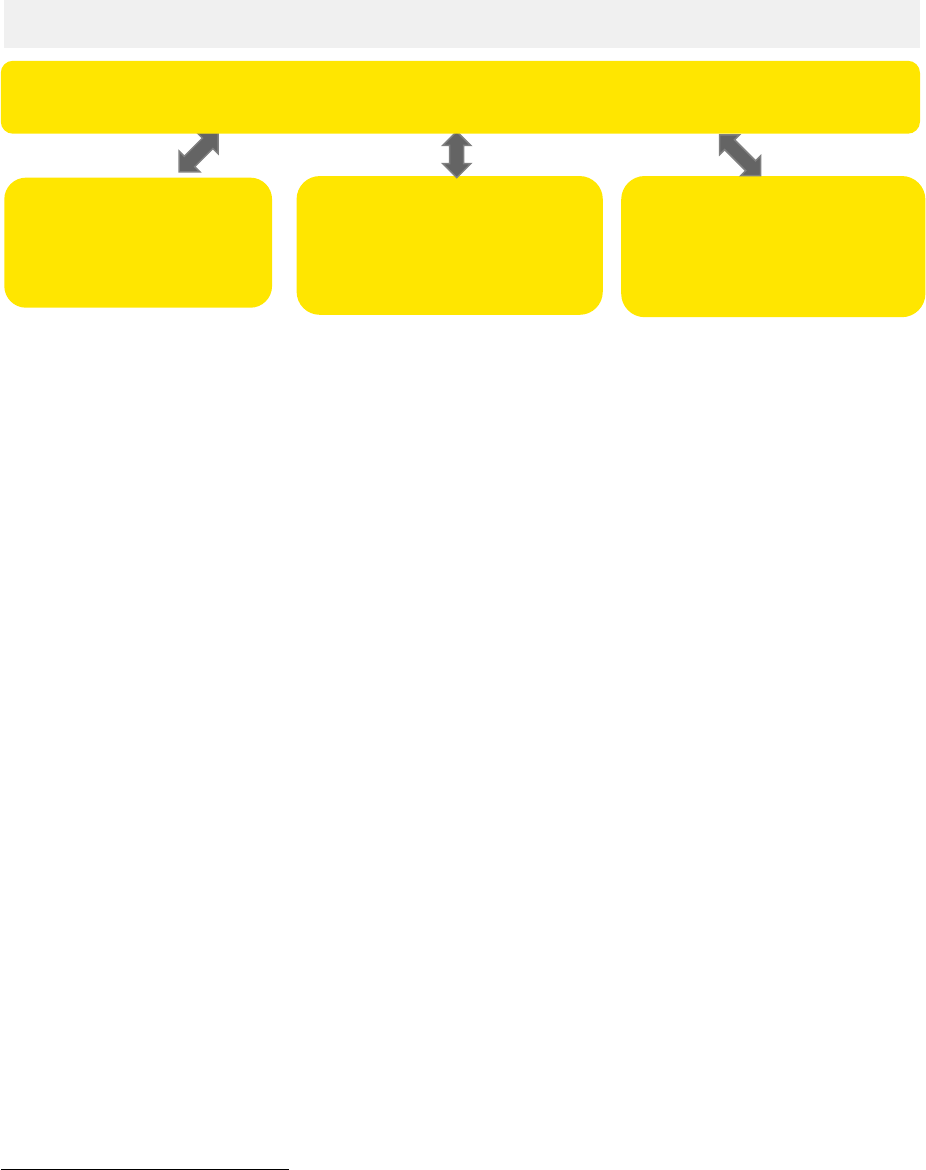

1.1.2 Executive summary of the five-step revenue model (updated September 2022)

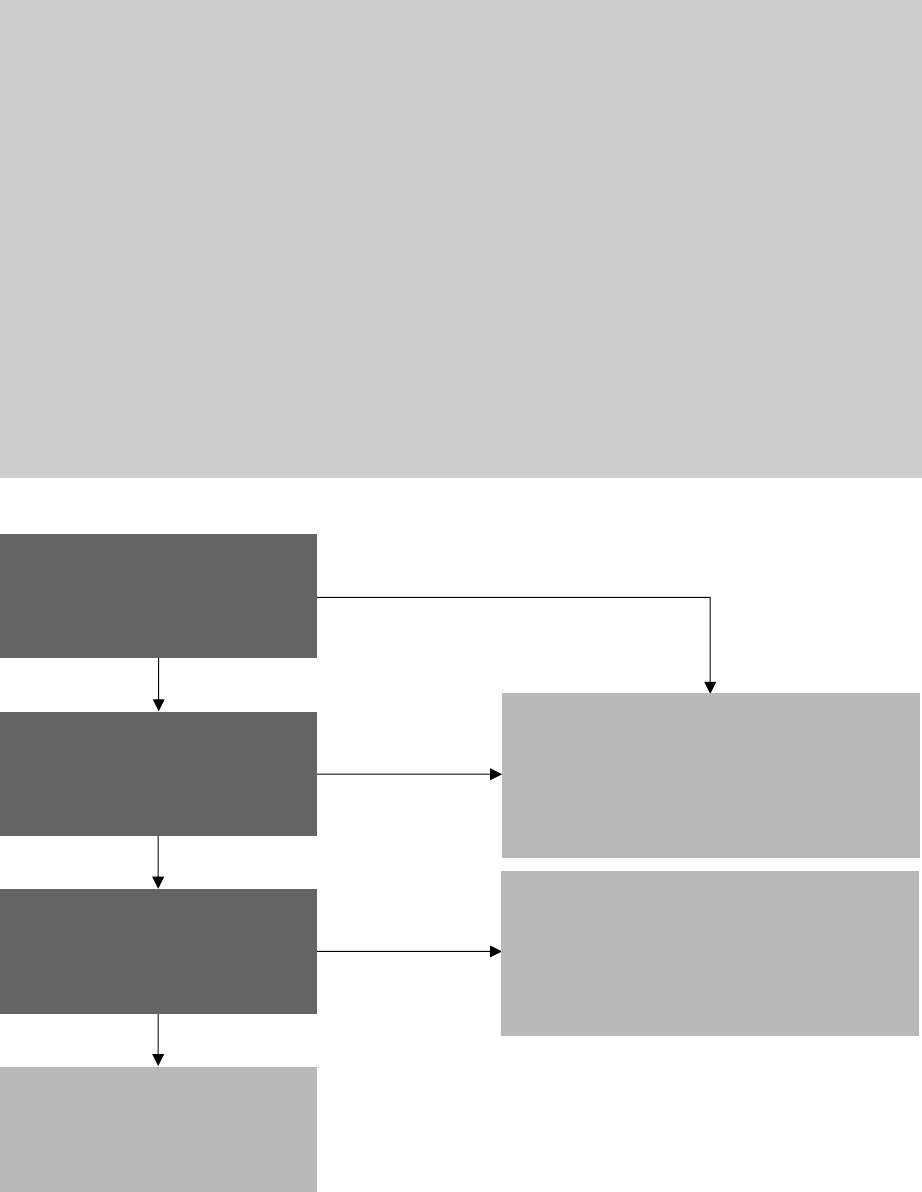

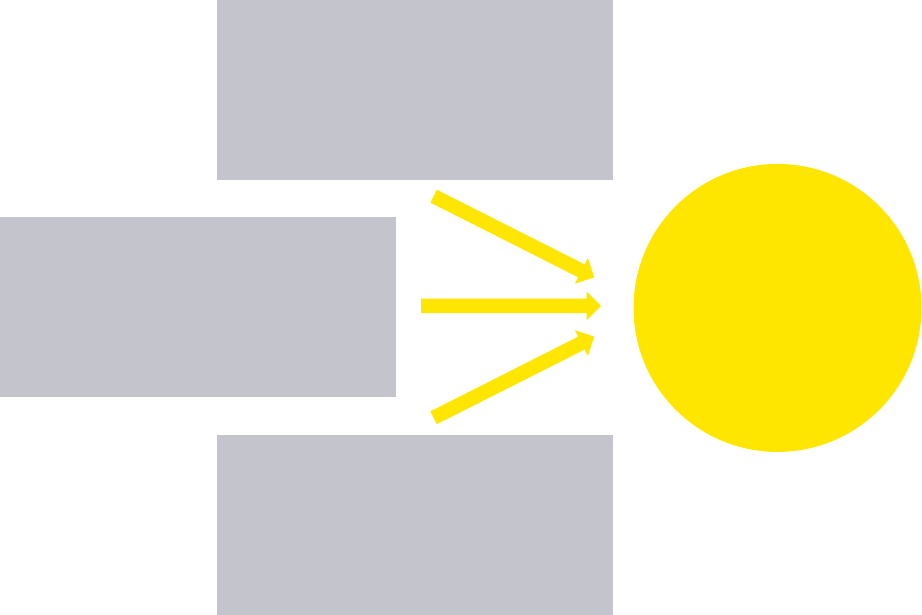

The standard’s core revenue principle is applied using the following five steps, which are summarized below:

Step 1

Identify the contract(s) with a customer

Step 2

Identify the performance obligations in the contract

Step 3

Determine the transaction price

Step 4

Allocate the transaction price to the performance obligations in the contract

Step 5

Recognize revenue when (or as) the entity satisfies a performance obligation

1 Overview

Financial reporting developments Revenue from contracts with customers (ASC 606) | 3

Step 1

Identify the contract(s) with a customer (see section 3)

Definition of a contract

An entity must first identify the contract, or contracts, to provide goods and services to customers. A

contract must create enforceable rights and obligations to fall within the scope of the model in the

standard. Such contracts may be written, oral or implied by an entity’s customary business practices but

must also meet the following criteria:

• The parties to the contract have approved the contract (in writing, orally or based on their customary

business practices) and are committed to perform their respective obligations

• The entity can identify each party’s rights regarding the goods or services to be transferred

• The entity can identify the payment terms for the goods or services to be transferred

• The contract has commercial substance (i.e., the risk, timing or amount of the entity’s future cash

flows is expected to change as a result of the contract)

• It is probable that the entity will collect substantially all of the consideration to which it will be

entitled in exchange for the goods or services that will be transferred to the customer

If these criteria are not met, an entity would not account for the arrangement using the model in the

standard and would recognize any nonrefundable consideration received as revenue only when certain

events have occurred.

Contract combination

The standard requires entities to combine contracts entered into at or near the same time with the same

customer (or related parties of the customer) if they meet any of the following criteria:

• The contracts are negotiated as a package with a single commercial objective

• The amount of consideration to be paid in one contract depends on the price or performance of

another contract

• The goods or services promised in the contracts (or some goods or services promised in each of the

contracts) are a single performance obligation

Contract modifications

A contract modification is a change in the scope and/or price of a contract that either creates new or

changes existing enforceable rights and obligations of the parties to the contract. A contract modification

is accounted for as a new contract separate from the original contract if the modification adds distinct

goods or services at a price that reflects the standalone selling prices of those goods or services.

Contract modifications that are not accounted for as separate contracts are considered changes to the

original contract and are accounted for as follows:

• If the goods and services to be transferred after the contract modification are distinct from the

goods or services transferred on or before the contract modification, the entity should account for

the modification as if it were the termination of the old contract and the creation of a new contract.

• If the goods and services to be transferred after the contract modification are not distinct from the

goods and services already provided and, therefore, form part of a single performance obligation

that is partially satisfied at the date of modification, the entity should account for the contract

modification as if it were part of the original contract.

• A combination of the two approaches above: a modification of the existing contract for the partially

satisfied performance obligations and the creation of a new contract for the distinct goods and services.

1 Overview

Financial reporting developments Revenue from contracts with customers (ASC 606) | 4

Step 2

Identify the performance obligations in the contract (see section 4)

An entity must identify the promised goods and services within the contract and determine which of those

goods and services (or bundles of goods and services) are separate performance obligations (i.e., the unit

of accounting for purposes of applying the standard). An entity is not required to assess whether promised

goods or services are performance obligations if they are immaterial in the context of the contract.

A promised good or service represents a performance obligation if (1) the good or service is distinct (by

itself or as part of a bundle of goods or services) or (2) the good or service is part of a series of distinct

goods or services that are substantially the same and have the same pattern of transfer to the customer.

A good or service (or bundle of goods or services) is distinct if both of the following criteria are met:

• The customer can benefit from the good or service either on its own or together with other resources

that are readily available to the customer (i.e., the good or service is capable of being distinct).

• The entity’s promise to transfer the good or service to the customer is separately identifiable from

other promises in the contract (i.e., the promise to transfer the good or service is distinct within the

context of the contract).

In assessing whether an entity’s promise to transfer a good or service is separately identifiable from other

promises in the contract, entities need to consider whether the nature of the promise is to transfer each of

those goods or services individually or to transfer a combined item or items to which the promised goods or

services are inputs. Factors that indicate that two or more promises to transfer goods or services are not

separately identifiable include, but are not limited to, the following:

• The entity provides a significant service of integrating the goods or services with other goods or

services promised in the contract into a bundle of goods or services that represent the combined

output or outputs for which the customer has contracted.

• One or more of the goods or services significantly modify or customize, or are significantly modified

or customized by, one or more of the other goods or services promised in the contract.

• The goods or services are highly interdependent or highly interrelated. In other words, each of the

goods or services is significantly affected by one or more of the other goods or services in the

contract (i.e., there is a significant two-way dependency).

If a promised good or service is not distinct, an entity is required to combine that good or service with

other promised goods or services until it identifies a bundle of goods or services that is distinct.

Series guidance

Goods or services that are part of a series of distinct goods or services that are substantially the same

and have the same pattern of transfer to the customer must be combined into one performance

obligation. To meet the same pattern of transfer criterion, each distinct good or service in the series

must represent a performance obligation that would be satisfied over time and would have the same

measure of progress toward satisfaction of the performance obligation (both discussed in Step 5), if

accounted for separately.

Principal versus agent considerations

When more than one party is involved in providing goods or services to a customer, an entity must

determine whether it is a principal or an agent in these transactions by evaluating the nature of its

promise to the customer. An entity is a principal and, therefore, records revenue on a gross basis if it

controls the specified good or service before transferring that good or service to the customer. An entity

is an agent and records as revenue the net amount it retains for its agency services if its role is to

1 Overview

Financial reporting developments Revenue from contracts with customers (ASC 606) | 5

arrange for another entity to provide the specified goods or services. Because it is not always clear

whether an entity controls a specified good or service in some contracts (e.g., those involving intangible

goods and/or services), the standard also provides indicators of when an entity may control the specified

good or service as follows:

• The entity is primarily responsible for fulfilling the promise to provide the specified good or service.

• The entity has inventory risk before the specified good or service has been transferred to a customer

or after transfer of control to the customer (e.g., if the customer has a right of return).

• The entity has discretion in establishing the price for the specified good or service.

Customer options for additional goods or services

A customer’s option to acquire additional goods or services (e.g., an option for free or discounted goods

or services) is accounted for as a separate performance obligation if it provides a material right to the

customer that the customer would not receive without entering into the contract (e.g., a discount that

exceeds the range of discounts typically given for those goods or services to that class of customer in

that geographical area or market).

Step 3

Determine the transaction price (see section 5)

The transaction price is the amount of consideration to which an entity expects to be entitled in exchange

for transferring promised goods or services to a customer. When determining the transaction price,

entities need to consider the effects of all of the following:

Variable consideration

An entity needs to estimate any variable consideration (e.g., amounts that vary due to discounts, rebates,

refunds, price concessions or bonuses) using either the expected value method (i.e., a probability-weighted

amount method) or the most likely amount method (i.e., a method to choose the single most likely

amount in a range of possible amounts). An entity’s method selection is not a “free choice” and must be

based on which method better predicts the amount of consideration to which the entity will be entitled.

To include variable consideration in the estimated transaction price, the entity has to conclude that it is

probable that a significant revenue reversal will not occur in future periods. This “constraint” on variable

consideration is based on the probability of a reversal of an amount that is significant relative to cumulative

revenue recognized for the contract. The standard provides factors that increase the likelihood or

magnitude of a revenue reversal, including the following: the amount of consideration is highly susceptible

to factors outside the entity’s influence, the entity’s experience with similar types of contracts is limited or

that experience has limited predictive value, or the contract has a large number and broad range of possible

outcomes. The standard generally requires an entity to estimate variable consideration, including the

application of the constraint, at contract inception and update that estimate at each reporting date.

There are limited situations in which estimation of variable consideration may not be required.

Significant financing component

An entity needs to adjust the transaction price for the effects of the time value of money if the timing of

payments agreed to by the parties to the contract provides the customer or the entity with a significant

financing benefit. As a practical expedient, an entity can elect not to adjust the transaction price for the

effects of a significant financing component if the entity expects at contract inception that the period

between payment and performance will be one year or less.

1 Overview

Financial reporting developments Revenue from contracts with customers (ASC 606) | 6

Noncash consideration

When an entity receives, or expects to receive, noncash consideration (e.g., property, plant, and

equipment (PP&E), a financial instrument), the fair value of the noncash consideration at contract

inception is included in the transaction price.

Consideration paid or payable to the customer

Consideration payable to the customer includes cash amounts that an entity pays, or expects to pay, to

the customer, credits or other items (vouchers or coupons) that can be applied against amounts owed to

the entity or equity instruments granted in conjunction with selling goods or services. An entity should

account for consideration paid or payable to the customer as a reduction of the transaction price and,

therefore, of revenue unless the payment to the customer is in exchange for a distinct good or service.

However, if the payment to the customer exceeds the fair value of the distinct good or service received,

the entity should account for the excess amount as a reduction of the transaction price.

Step 4

Allocate the transaction price to the performance obligations in the contract (see section 6)

For contracts that have multiple performance obligations, the standard generally requires an entity to

allocate the transaction price to the performance obligations in proportion to their standalone selling prices

(i.e., on a relative standalone selling price basis). When allocating on a relative standalone selling price

basis, any discount within the contract generally is allocated proportionately to all of the performance

obligations in the contract. However, there are two exceptions.

One exception requires variable consideration to be allocated entirely to a specific part of a contract,

such as one or more (but not all) performance obligations or one or more (but not all) distinct goods or

services promised in a series of distinct goods or services that forms part of a single performance

obligation, if both of the following criteria are met:

• The terms of a variable payment relate specifically to the entity’s efforts to satisfy the performance

obligation or transfer the distinct good or service (or to a specific outcome from satisfying the

performance obligation or transferring the distinct good or service).

• Allocating the variable consideration entirely to the performance obligation or the distinct good or

service is consistent with the objective of allocating consideration in an amount that depicts the

consideration to which the entity expects to be entitled in exchange for transferring the promised

goods or services to the customer.

The other exception requires an entity to allocate a contract’s entire discount to only those goods or

services to which it relates if certain criteria are met.

To allocate the transaction price on a relative standalone selling price basis, an entity must first determine

the standalone selling price of the distinct good or service underlying each performance obligation. The

standalone selling price is the price at which an entity would sell a good or service on a standalone (or

separate) basis at contract inception. Under the model, the observable price of a good or service sold

separately in similar circumstances to similar customers provides the best evidence of the standalone

selling price. However, in many situations, standalone selling prices will not be readily observable. In

those cases, the entity must estimate the standalone selling price by considering all information that is

reasonably available to it, maximizing the use of observable inputs and applying estimation methods

consistently in similar circumstances. The standard states that suitable estimation methods include, but

are not limited to, an adjusted market assessment approach, an expected cost plus a margin approach or a

residual approach (if certain conditions are met).

1 Overview

Financial reporting developments Revenue from contracts with customers (ASC 606) | 7

Step 5

Recognize revenue when (or as) the entity satisfies a performance obligation (see section 7)

An entity recognizes revenue only when (or as) it satisfies a performance obligation by transferring

control of the promised good(s) or service(s) to a customer. The transfer of control can occur over time

or at a point in time.

A performance obligation is satisfied at a point in time unless it meets one of the following criteria, in

which case it is satisfied over time:

• The customer simultaneously receives and consumes the benefits provided by the entity’s

performance as the entity performs

• The entity’s performance creates or enhances an asset that the customer controls as the asset is

created or enhanced

• The entity’s performance does not create an asset with an alternative use to the entity, and the

entity has an enforceable right to payment for performance completed to date

The transaction price allocated to performance obligations satisfied at a point in time is recognized as

revenue when control of the goods or services transfers to the customer. If the performance obligation is

satisfied over time, the transaction price allocated to that performance obligation is recognized as

revenue as the performance obligation is satisfied. To do this, the standard requires an entity to select a

single revenue recognition method (i.e., measure of progress) that faithfully depicts the pattern of the

transfer of control over time (i.e., an input method or an output method).

1.1.3 Other recognition and measurement topics (updated September 2022)

Licenses of intellectual property (see section 8)

The standard provides guidance on the recognition of revenue for licenses of intellectual property that

differs from the model for other promised goods and services. The nature of the promise in granting a

license of intellectual property to a customer is either:

• A right to access the entity’s intellectual property throughout the license period (a right to access)

• A right to use the entity’s intellectual property as it exists at the point in time in which the license is

granted (a right to use)

To determine whether the entity’s promise is to provide a right to access its intellectual property or a

right to use its intellectual property, the entity should consider the nature of the intellectual property to

which the customer will have rights. The standard requires entities to classify intellectual property in one

of two categories:

• Functional: This intellectual property has significant standalone functionality (e.g., many types of

software; completed media content, such as films, television shows and music). Licenses of functional

intellectual property generally grant a right to use the entity’s intellectual property, and revenue for

these licenses generally is recognized at the point in time when the intellectual property is made

available for the customer’s use and benefit. This is the case if the functionality is not expected to

change substantially as a result of the licensor’s ongoing activities that do not transfer an additional

promised good or service to the customer. If the functionality of the intellectual property is expected to

substantively change because of activities of the licensor that do not transfer additional promised goods

or services, and the customer is contractually or practically required to use the latest version of the

intellectual property, revenue for the license is recognized over time. However, we expect licenses of

functional intellectual property to meet the criteria to be recognized over time infrequently, if at all.

1 Overview

Financial reporting developments Revenue from contracts with customers (ASC 606) | 8

• Symbolic: This intellectual property does not have significant standalone functionality (e.g., brands, team

and trade names, character images). The utility (i.e., the ability to provide benefit or value) of symbolic

intellectual property is largely derived from the licensor’s ongoing or past activities (e.g., activities that

support the value of character images). Licenses of symbolic intellectual property grant a right to access

an entity’s intellectual property, and revenue from these licenses is recognized over time as the

performance obligation is satisfied (e.g., over the license period).

Revenue cannot be recognized from a license of intellectual property before both (1) an entity provides

(or otherwise makes available) a copy of the intellectual property to the customer and (2) the beginning

of the period during which the customer is able to use and benefit from its right to access or its right to

use the intellectual property.

The standard specifies that sales and usage-based royalties on licenses of intellectual property are recognized

when the later of the following events occurs: (1) the subsequent sales or usage occurs or (2) the

performance obligation to which some or all of the sales-based or usage-based royalty has been allocated

has been satisfied (or partially satisfied). This guidance must be applied to the overall royalty stream when

the sole or predominant item to which the royalty relates is a license of intellectual property (i.e., these types

of arrangements are either entirely in the scope of this guidance or entirely in the scope of the general

variable consideration constraint guidance).

Contract costs (see section 9)

ASC 340-40 specifies the accounting for costs an entity incurs to obtain and fulfill a contract to provide

goods and services to customers. The incremental costs of obtaining a contract (i.e., costs that would not

have been incurred if the contract had not been obtained) are recognized as an asset if the entity expects

to recover them. ASC 340-40 cites commissions as a type of incremental cost that may require

capitalization. Further, ASC 340-40 provides a practical expedient that permits an entity to immediately

expense contract acquisition costs when the asset that would have resulted from capitalizing these costs

would have been amortized in one year or less.

An entity accounts for costs incurred to fulfill a contract with a customer that are within the scope of

other authoritative guidance (e.g., inventory, PP&E, internal-use software) in accordance with that

guidance. If the costs are not in the scope of other accounting guidance, an entity recognizes an asset

from the costs incurred to fulfill a contract only if those costs meet all of the following criteria:

• The costs relate directly to a contract or to an anticipated contract that the entity can specifically identify.

• The costs generate or enhance resources of the entity that will be used in satisfying (or in continuing

to satisfy) performance obligations in the future.

• The costs are expected to be recovered.

Any capitalized contract costs are amortized, with the expense recognized as an entity transfers the related

goods or services to the customer. Any asset recorded by the entity is subject to an impairment assessment.

Financial reporting developments Revenue from contracts with customers (ASC 606) | 9

2 Scope

ASC 606 applies to all entities and all contracts with customers to provide goods or services in the ordinary

course of business, except for contracts or transactions that are excluded from its scope, as described below.

Excerpt from Accounting Standards Codification

Revenue from Contracts with Customers — Overall

Scope and Scope Exceptions

Entities

606-10-15-1

The guidance in this Subtopic applies to all entities.

Transactions

606-10-15-2

An entity shall apply the guidance in this Topic to all contracts with customers, except the following:

a. Lease contracts within the scope of Topic 842, Leases.

b. Contracts within the scope of Topic 944, Financial Services—Insurance.

c. Financial instruments and other contractual rights or obligations within the scope of the following Topics:

1. Topic 310, Receivables

2. Topic 320, Investments—Debt Securities

2a. Topic 321, Investments—Equity Securities

3. Topic 323, Investments—Equity Method and Joint Ventures

4. Topic 325, Investments—Other

5. Topic 405, Liabilities

6. Topic 470, Debt

7. Topic 815, Derivatives and Hedging

8. Topic 825, Financial Instruments

9. Topic 860, Transfers and Servicing.

d. Guarantees (other than product or service warranties) within the scope of Topic 460, Guarantees.

e. Nonmonetary exchanges between entities in the same line of business to facilitate sales to

customers or potential customers. For example, this Topic would not apply to a contract between

two oil companies that agree to an exchange of oil to fulfill demand from their customers in

different specified locations on a timely basis. Topic 845 on nonmonetary transactions may apply

to nonmonetary exchanges that are not within the scope of this Topic.

606-10-15-2A

An entity shall consider the guidance in Subtopic 958-605 on not-for-profit entities — revenue

recognition — contributions when determining whether a transaction is a contribution within the scope

of Subtopic 958-605 or a transaction within the scope of this Topic.

2 Scope

Financial reporting developments Revenue from contracts with customers (ASC 606) | 10

606-10-15-3

An entity shall apply the guidance in this Topic to a contract (other than a contract listed in paragraph

606-10-15-2) only if the counterparty to the contract is a customer. A customer is a party that has

contracted with an entity to obtain goods or services that are an output of the entity’s ordinary activities in

exchange for consideration.

2.1 Other scope considerations (updated September 2023)

Certain agreements executed by entities include repurchase provisions, either as a component of a sales

contract or as a separate contract that relates to the same or similar goods in the original agreement.

The form of the repurchase agreement and whether the customer obtains control of the asset subject to

the agreement will determine whether the agreement is within the scope of the standard. See section 7.3

for a discussion on repurchase agreements.

Entities may enter into transactions that are partially within the scope of ASC 606 and partially within the

scope of other guidance. In these situations, the standard requires an entity to first apply any separation

and/or measurement principles in the other guidance before applying the revenue standard. See section 2.4

for further discussion. For example, if a contract is a lease or contains a lease, entities would first

consider the separation and measurement principles in ASC 842 and the modification guidance in

ASC 842, if the contract is modified, before applying the revenue standard. We further discuss the

interaction of ASC 606 and ASC 842 in Question 3-22 in section 3.4 and Question 6-12 in section 6.5.

The standard also refers to the guidance in ASC 340-40 for the accounting for certain costs, such as the

incremental costs of obtaining a contract and the costs of fulfilling a contract. However, ASC 340-40

requires that the guidance on costs of fulfilling a contract be applied only if there is no other guidance for

accounting for these costs. See section 9.3 for further discussion of the cost guidance in the standard.

In addition, the standard provides a model for the measurement and recognition of a gain or loss on the

transfer of certain nonfinancial assets (e.g., assets within the scope of ASC 360 and intangible assets

within the scope of ASC 350). See our FRD, Gains and losses from the derecognition of nonfinancial assets

(ASC 610-20), for further details.

2.1.1 Nonmonetary exchanges

ASC 606 provides guidance for contracts with customers involving noncash consideration in exchange for

goods or services (see section 5.6). As a result, the FASB excluded contracts with customers that are in

the scope of ASC 606 from the scope of ASC 845 on nonmonetary transactions. The FASB also included a

scope exception in ASC 606-10-15-2(e) that excludes nonmonetary exchanges between entities in the same

line of business to facilitate sales to customers or potential customers from the scope of ASC 606.

Accordingly, the scope of ASC 845 includes exchanges of products that are held for sale in the ordinary

course of business to facilitate sales to customers (i.e., parties outside of the exchange), while the scope

of ASC 606 includes transfers to customers of goods or services that are an output of an entity’s

ordinary activities in exchange for noncash consideration.

For example, if an entity transfers its finished goods to a customer in exchange for noncash consideration,

that transaction would generally be in the scope of ASC 606 because finished goods are typically an output

of the entity’s ordinary activities. Conversely, ASC 606-10-15-2(e) states that ASC 606 “would not apply to

a contract between two oil companies that agree to an exchange of oil to fulfill demand from their customers

in different specified locations on a timely basis.” ASC 845 may apply to nonmonetary exchanges that are

not within the scope of ASC 606, if they are not within the scope of other guidance (e.g., ASC 610-20).

2 Scope

Financial reporting developments Revenue from contracts with customers (ASC 606) | 11

Entities in the same line of business would likely account for an exchange of finished goods for raw materials

or work-in-process inventory under the noncash consideration guidance in ASC 606 because we believe

the scope exception in ASC 606-10-15-2(e) would not apply. In addition, ASC 845-10-30-15 states, “A

nonmonetary exchange whereby an entity transfers finished goods inventory in exchange for the receipt

of raw materials or work-in-process inventory within the same line of business is not an exchange transaction

to facilitate sales to customers.” See sections N1.2.2 and N1.2.3 of our Accounting Manual, Nonmonetary

transactions, for further discussion on ASC 845 scoping, and recognition and measurement, respectively.

The following examples illustrate the scoping considerations for ASC 606 and ASC 845:

Illustration 2-1: Transaction in the scope of ASC 845

An automobile dealer exchanges new models with another dealer to obtain the color ordered by a

customer. This exchange is intended to facilitate a sale to a customer who is not a party to the exchange

and involves inventory held for sale in the ordinary course of business, and the automobile dealers are

in the same line of business. Accordingly, this transaction is in the scope of ASC 845.

Illustration 2-2: Transaction in the scope of ASC 606

An office supply retailer provides office equipment and supplies to an automobile dealer in exchange

for an automobile. The automobile dealer will use the office equipment and supplies in its financing

department. The new equipment is an upgrade from the automobile dealer’s old equipment and will

allow the automobile dealer to reduce administrative expenses. The office supply retailer will use the

car received in its repair department, allowing the department to reduce response times and meet

service level commitments. Although the exchange involves products held for sale by each entity, the

transaction is not an exchange of a product held for sale in the ordinary course of business for a

product to be sold in the same line of business to facilitate sales to customers.

Because each entity is selling its products to a customer (i.e., the sales are outputs of each entity’s

ordinary activities), the transaction is in the scope of ASC 606 for each entity.

2.2 Definition of a customer

The standard defines a customer as “a party that has contracted with an entity to obtain goods or services

that are an output of the entity’s ordinary activities in exchange for consideration.” The standard does not

define the term “ordinary activities” because it was derived from the definitions of revenue in the respective

conceptual frameworks of the IASB and the FASB in effect when the standards were developed.

5

In particular,

the IASB’s 2010 Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting referred specifically to the “ordinary

activities of an entity” and the definition of revenue in the FASB’s superseded CON 6

6

referred to the

notion of an entity’s “ongoing major or central operations.” In many transactions, a customer is easily

identifiable. However, in transactions involving multiple parties, it may be less clear which counterparties

are customers of an entity. For some arrangements, multiple parties could be considered customers of

the entity. For other arrangements, only one of the parties involved is considered a customer.

5

Paragraph BC53 of ASU 2014-09.

6

In December 2021, the FASB superseded CON 6 with CON 8, which defines revenue as “inflows or other enhancements of assets

of an entity or settlements of its liabilities (or a combination of both) from delivering or producing goods, rendering services, or

carrying out other activities.” However, the definition of revenue in ASC 606 did not change.

2 Scope

Financial reporting developments Revenue from contracts with customers (ASC 606) | 12

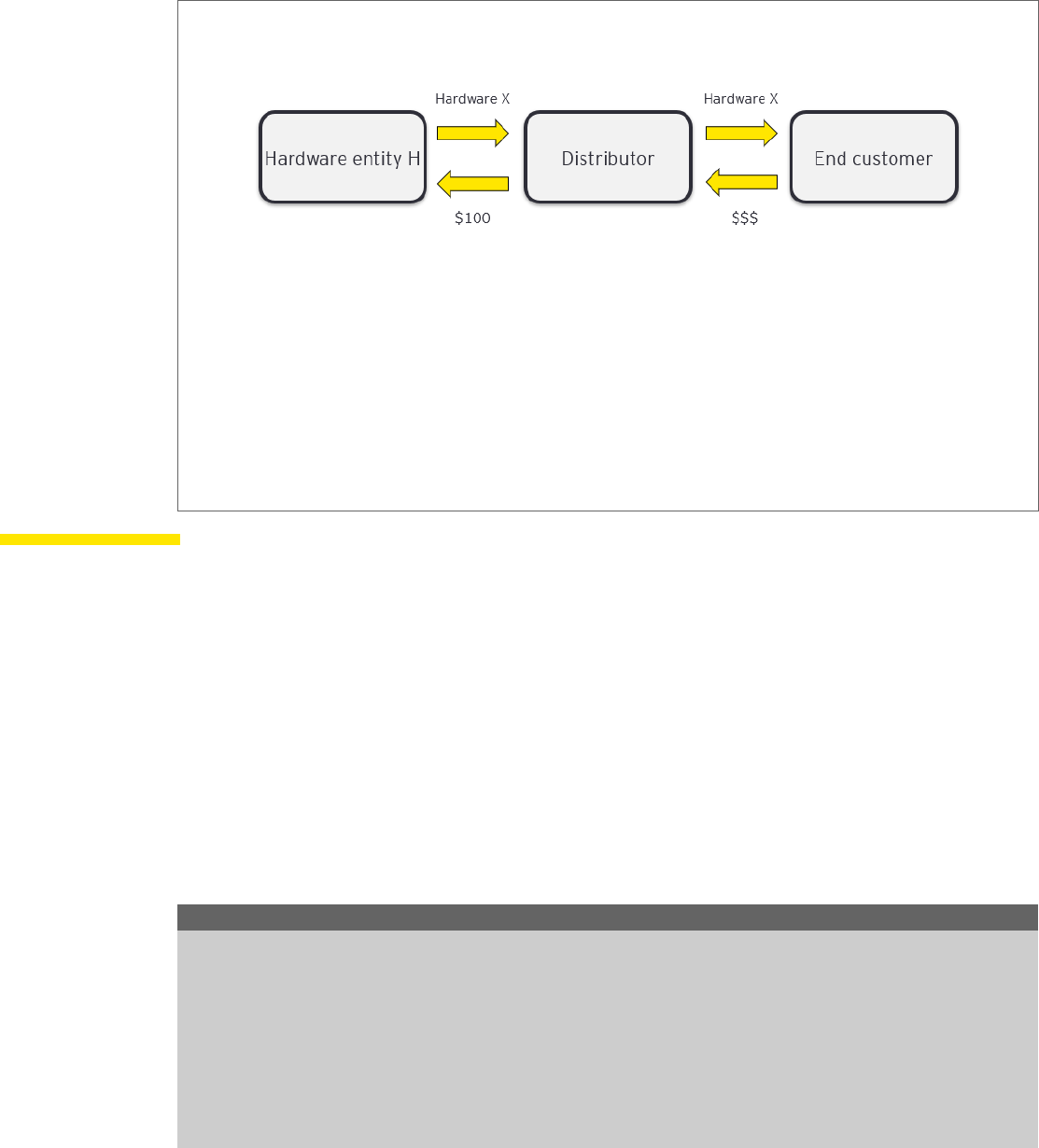

The illustration below shows how the party considered to be the customer may differ, depending

on the arrangement:

Illustration 2-3: Identification of a customer

An entity provides internet-based advertising services to companies. As part of that service, the entity

obtains banner space on various websites from a selection of publishers. For certain contracts, the

entity provides a sophisticated service of matching the ad placement with the pre-identified criteria of

the advertising party. In addition, the entity purchases the advertising space from the publishers before it

finds advertisers for that space. Assume that the entity appropriately concludes it is acting as the principal in

these contracts (see section 4.4 for further discussion of principal versus agent considerations). Accordingly,

the entity identifies its customer in this transaction as the advertiser to whom it is providing services.

In other contracts, the entity simply matches advertisers with the publishers in its portfolio, but the entity does

not provide any ad-targeting services or purchase the advertising space from the publishers before it finds

advertisers for that space. Assume that the entity appropriately concludes it is acting as the agent in these

contracts. Accordingly, the entity identifies its customer as the publisher to whom it is providing services.

In addition, the identification of the performance obligations in a contract (discussed further in section 4)

can have a significant effect on the determination of which party is the entity’s customer.

Also see the discussion of the identification of an entity’s customer when applying the guidance on

consideration paid or payable to a customer in section 5.7.

2.3 Collaborative arrangements

Entities often enter into collaborative arrangements to, for example, jointly develop and commercialize

intellectual property, such as a drug candidate in the life sciences industry or a motion picture in the

entertainment industry. In such arrangements, the counterparty may not be a “customer” of the entity.

Instead, the counterparty may be a collaborator or partner that shares in the risks and benefits of developing

a product to be marketed. These transactions, which are common in the pharmaceutical, biotechnology, oil

and gas, and health care industries, generally are in the scope of ASC 808 on collaborative arrangements.

However, depending on the facts and circumstances, these arrangements may also contain a vendor-

customer aspect. Such arrangements could still be within the scope of ASC 606, at least partially, if that

collaborator or partner meets the definition of a customer for some or all aspects of the arrangement.

Therefore, the parties to such arrangements need to consider all facts and circumstances to determine

whether a vendor-customer relationship exists that is subject to the guidance in ASC 606.

Transactions in a collaborative arrangement should be accounted for under ASC 606 when the counterparty

is a customer for a good or service that is a distinct unit of account. However, a unit of account comprising

multiple goods and/or services (i.e., a distinct bundle of goods or services) would be outside the scope of

ASC 606 if it includes both transactions with a customer and transactions that are not with a customer.

For example, a combined unit of account that includes a license of intellectual property and research and

development activities is outside the scope of ASC 606 if the entity considers the license to be a vendor-

customer transaction and the research and development activities to be collaborative and not part of the

vendor-customer transaction. ASC 808 references the unit-of-account guidance in ASC 606 (i.e., Step 2

discussed in section 4) and requires it to be used only when assessing whether transactions in a

collaborative arrangement are in the scope of ASC 606.

2 Scope

Financial reporting developments Revenue from contracts with customers (ASC 606) | 13

For units of account in the scope of ASC 606, all guidance in ASC 606 applies, including the guidance on

recognition, measurement, presentation and disclosure. However, ASC 808 permits entities to apply some

or all of the principles in ASC 606 by analogy or as a policy election to transactions in the scope of ASC 808

if more relevant authoritative guidance doesn’t exist. An entity in this situation is not permitted to present

amounts related to transactions in the scope of ASC 808 as revenue from contracts with customers.

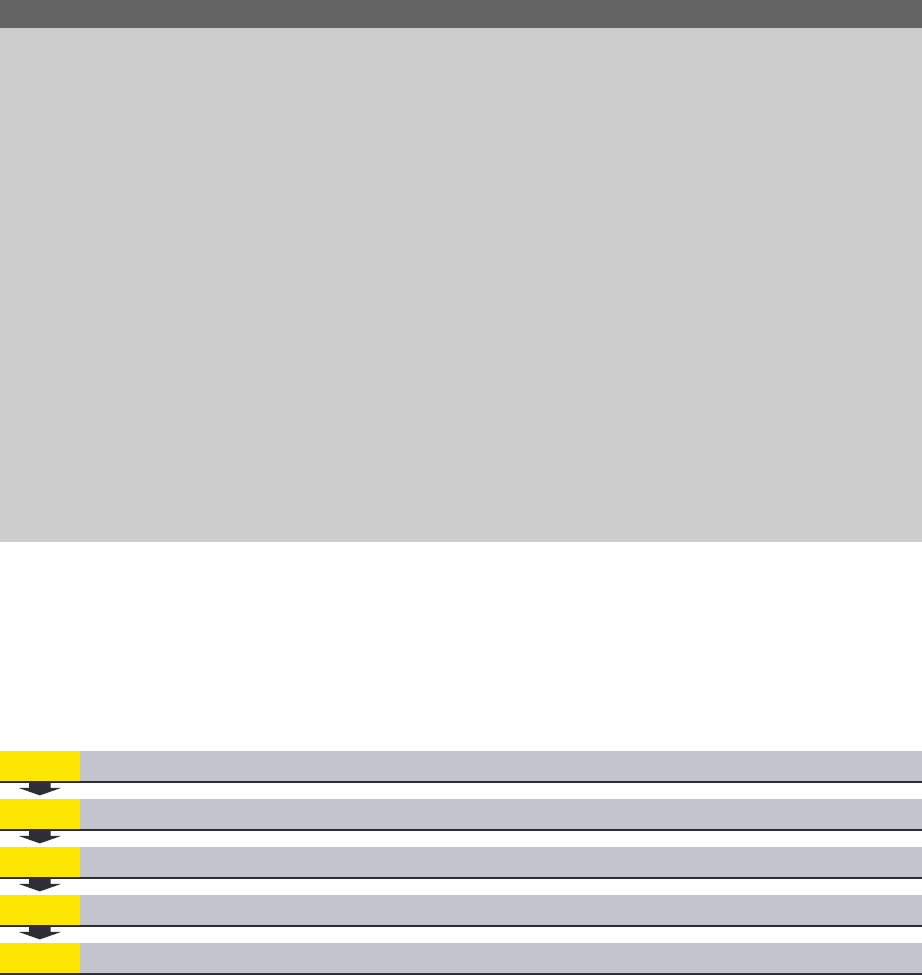

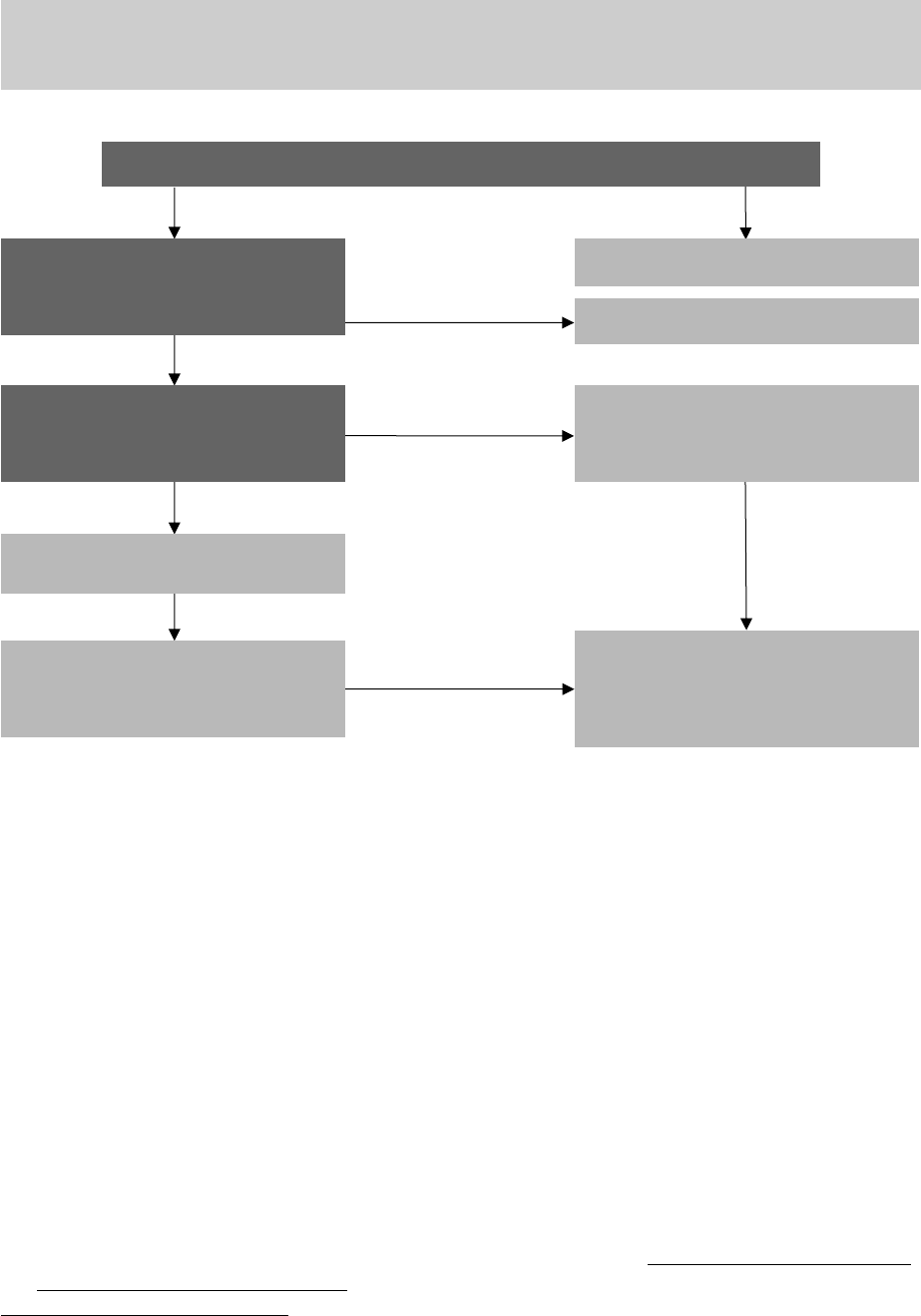

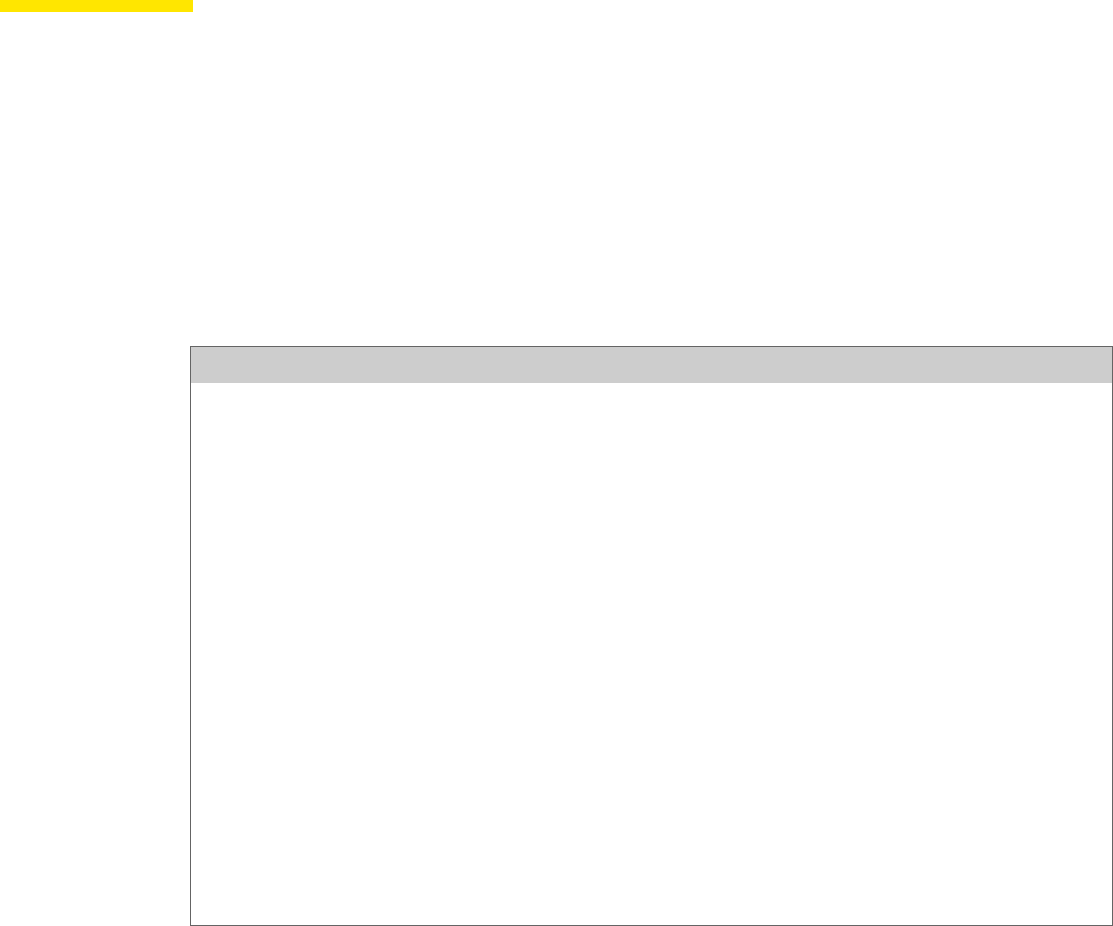

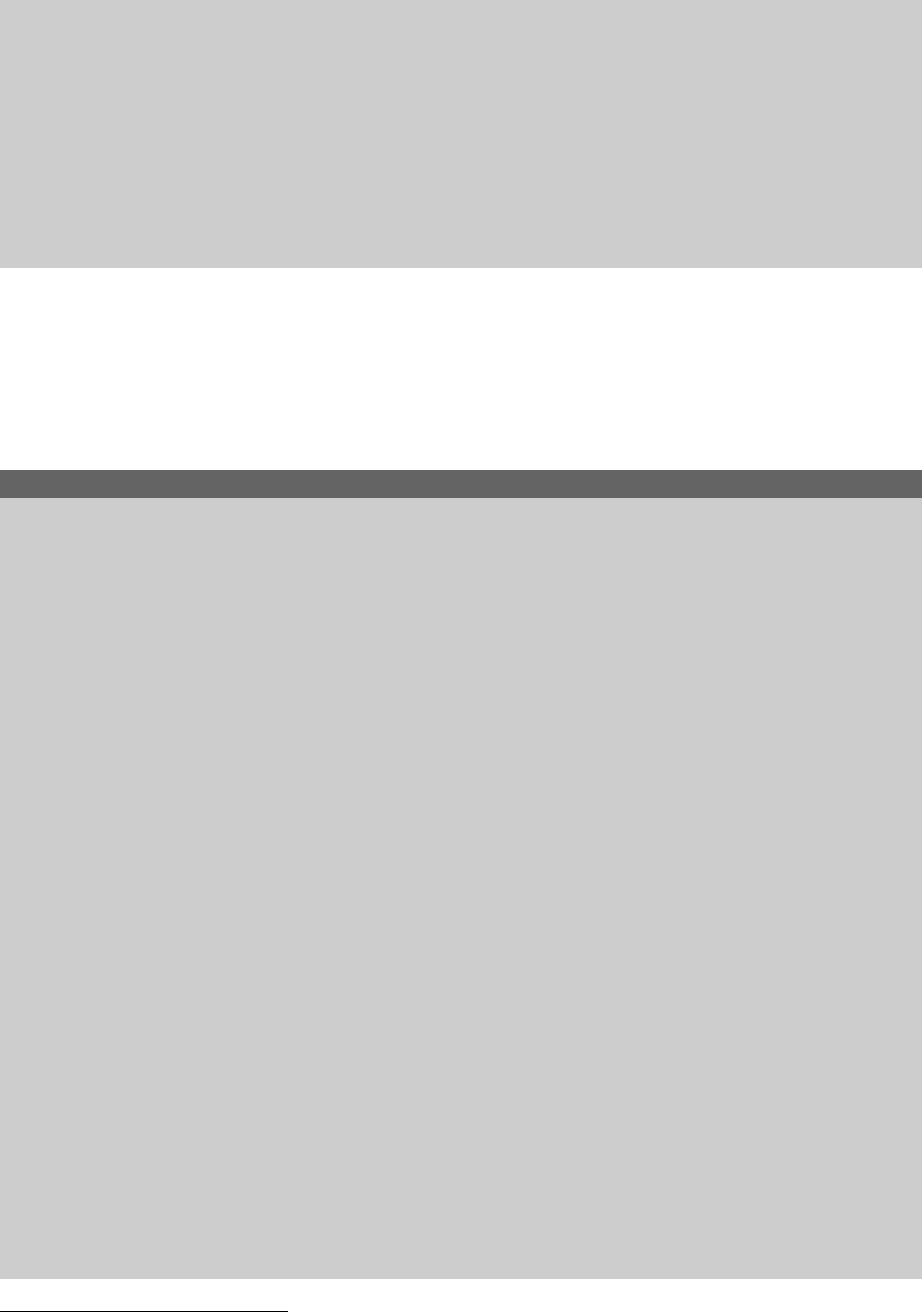

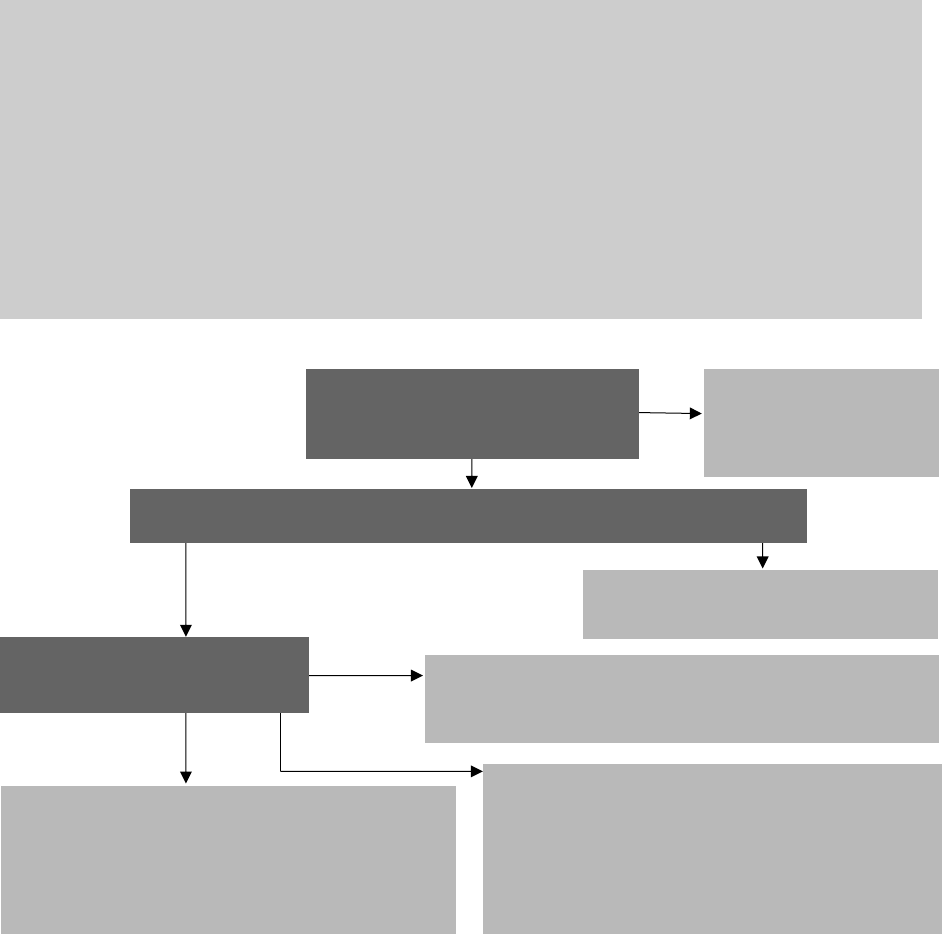

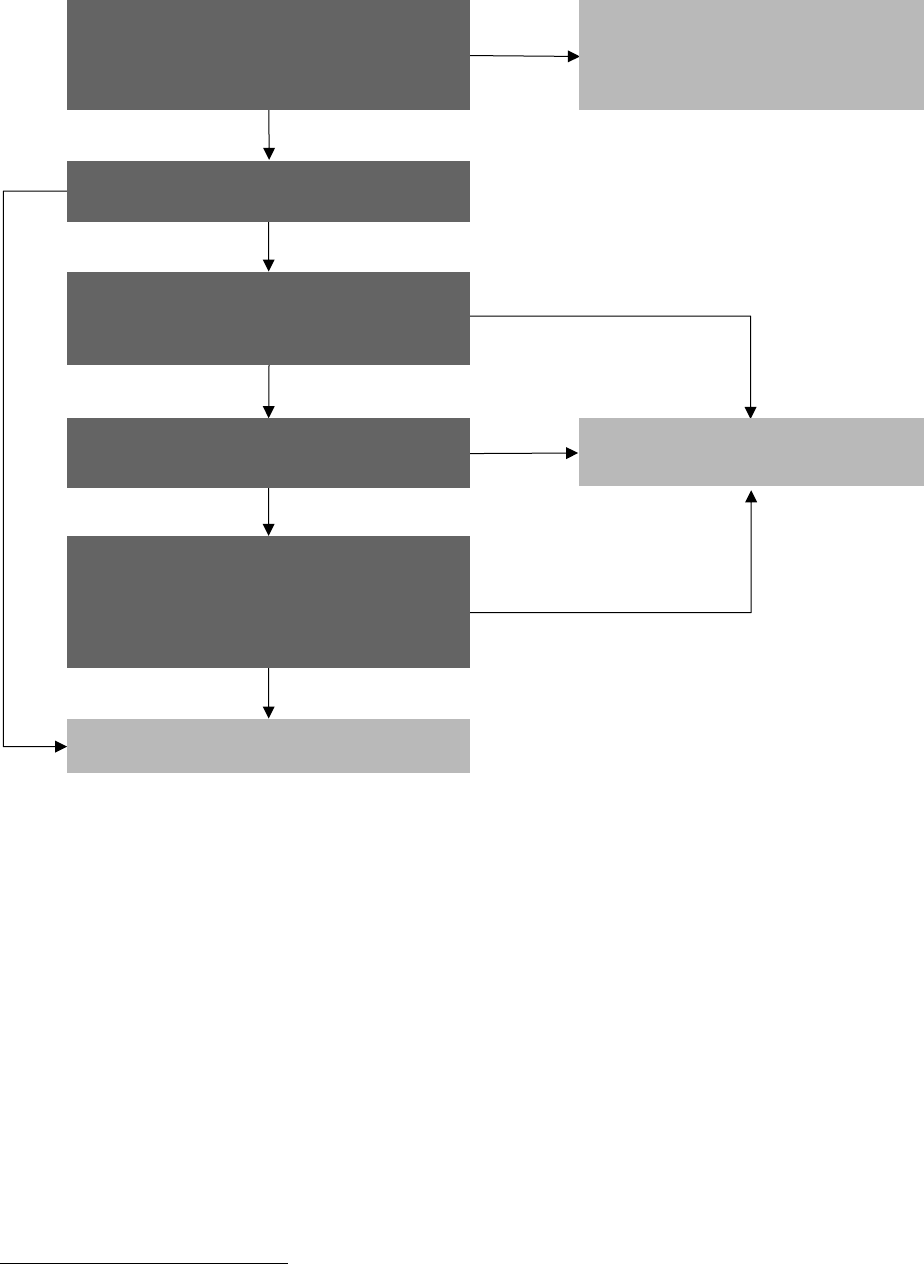

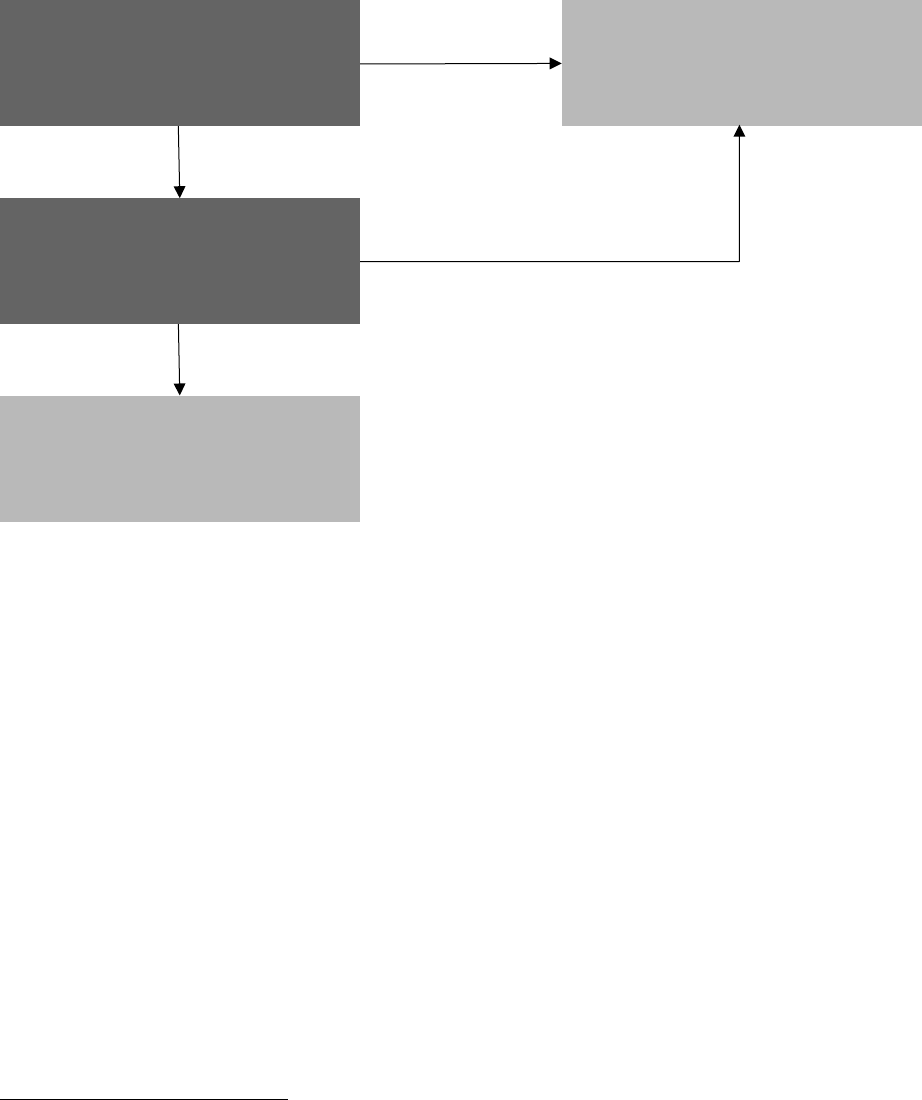

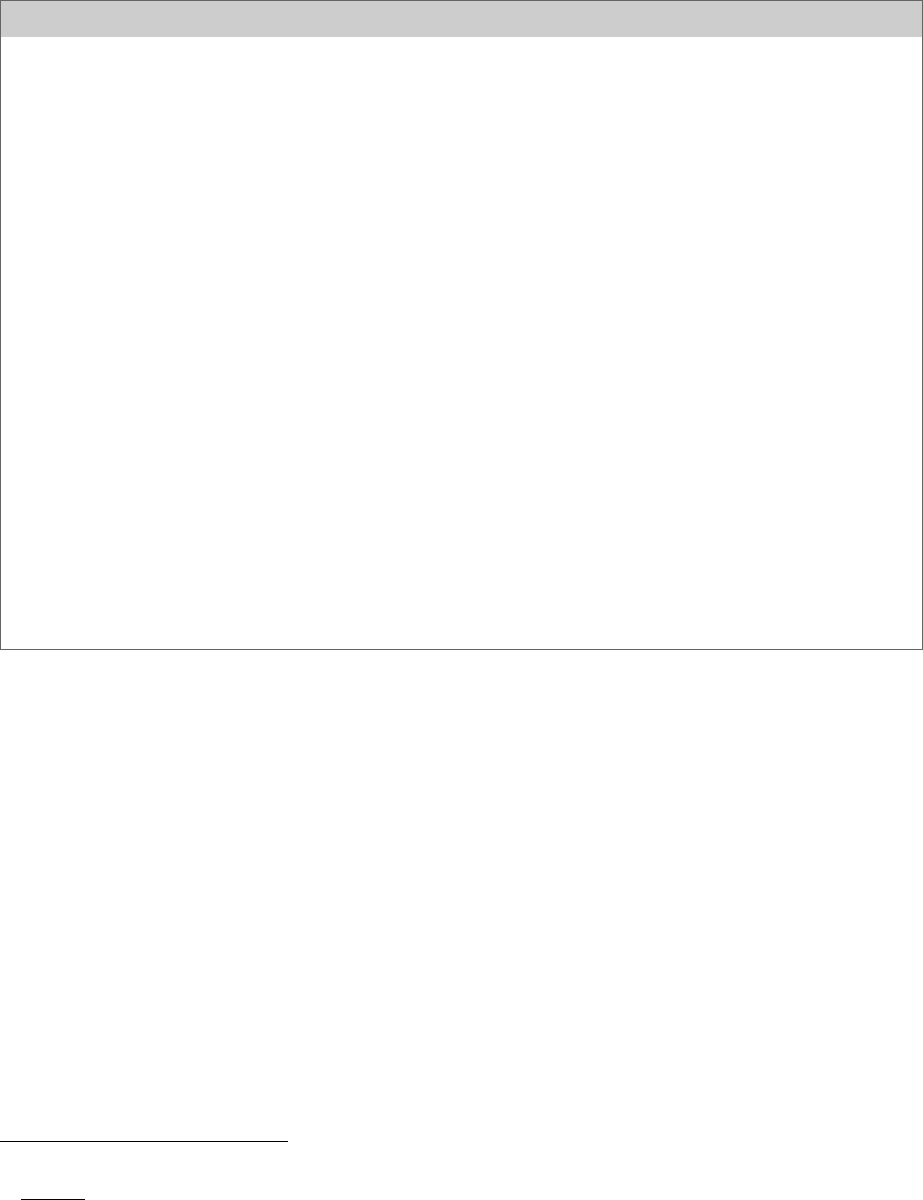

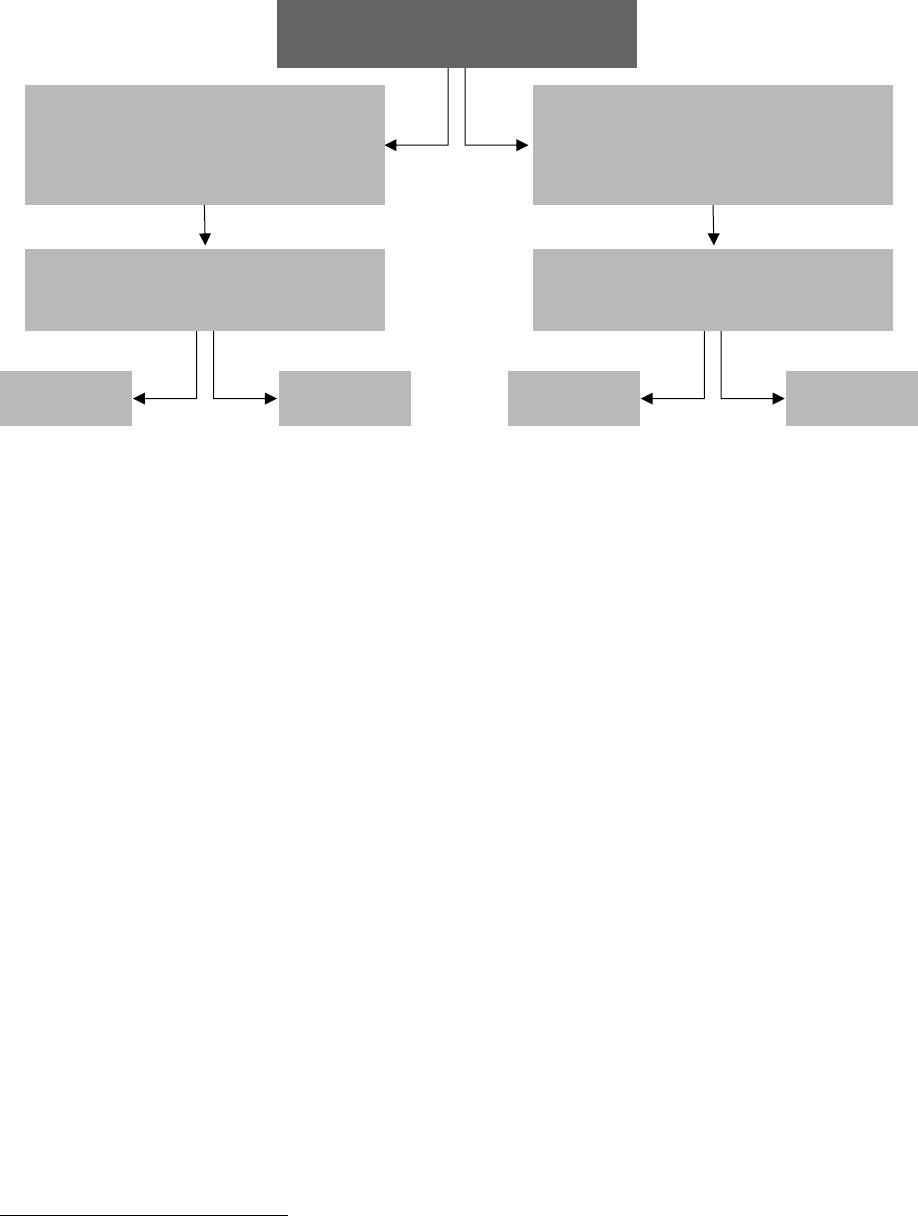

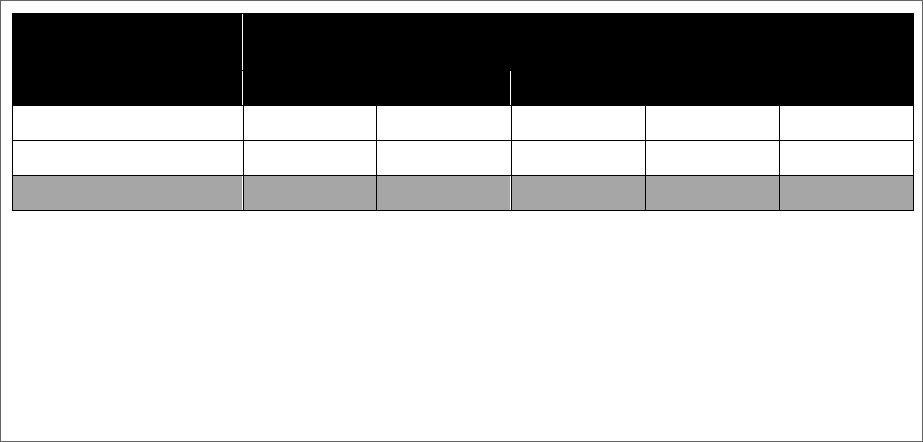

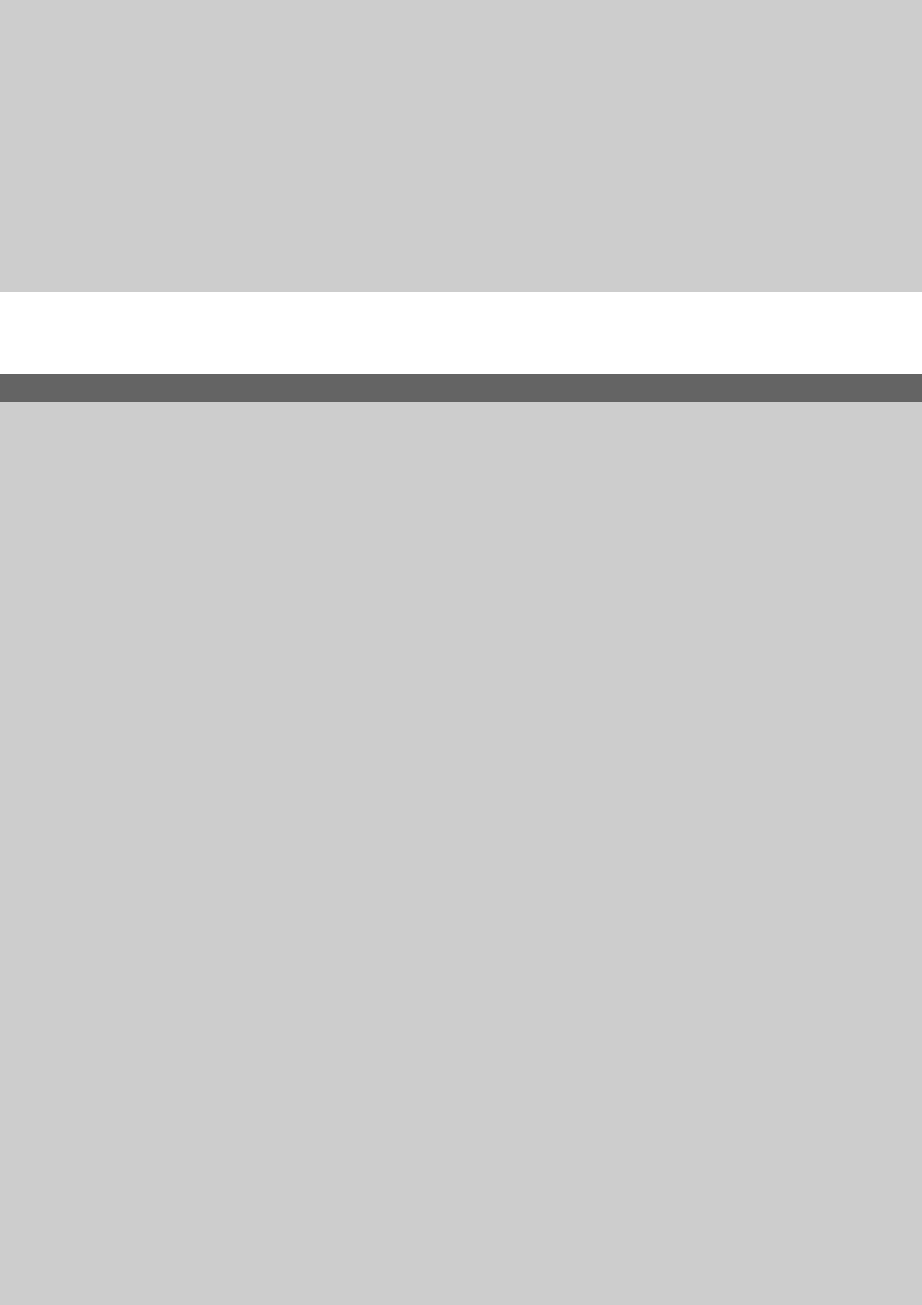

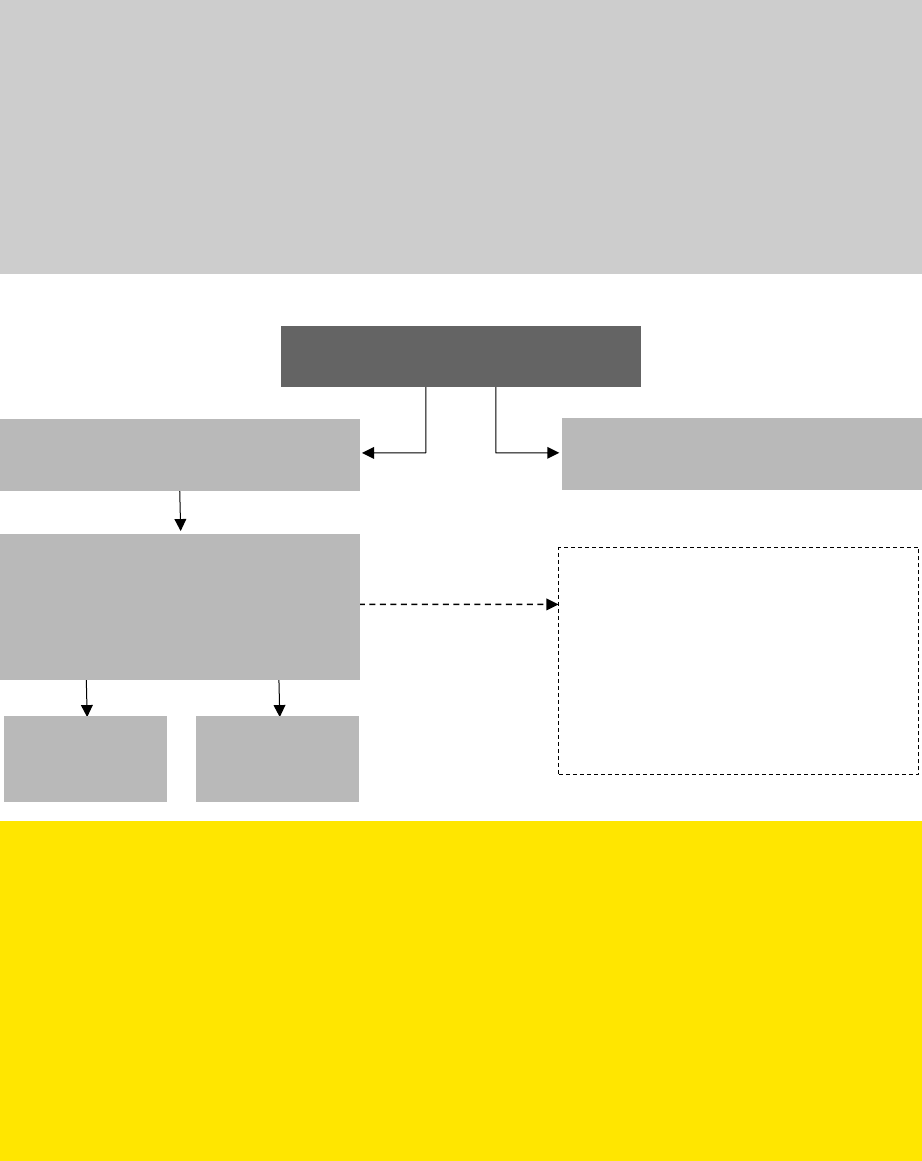

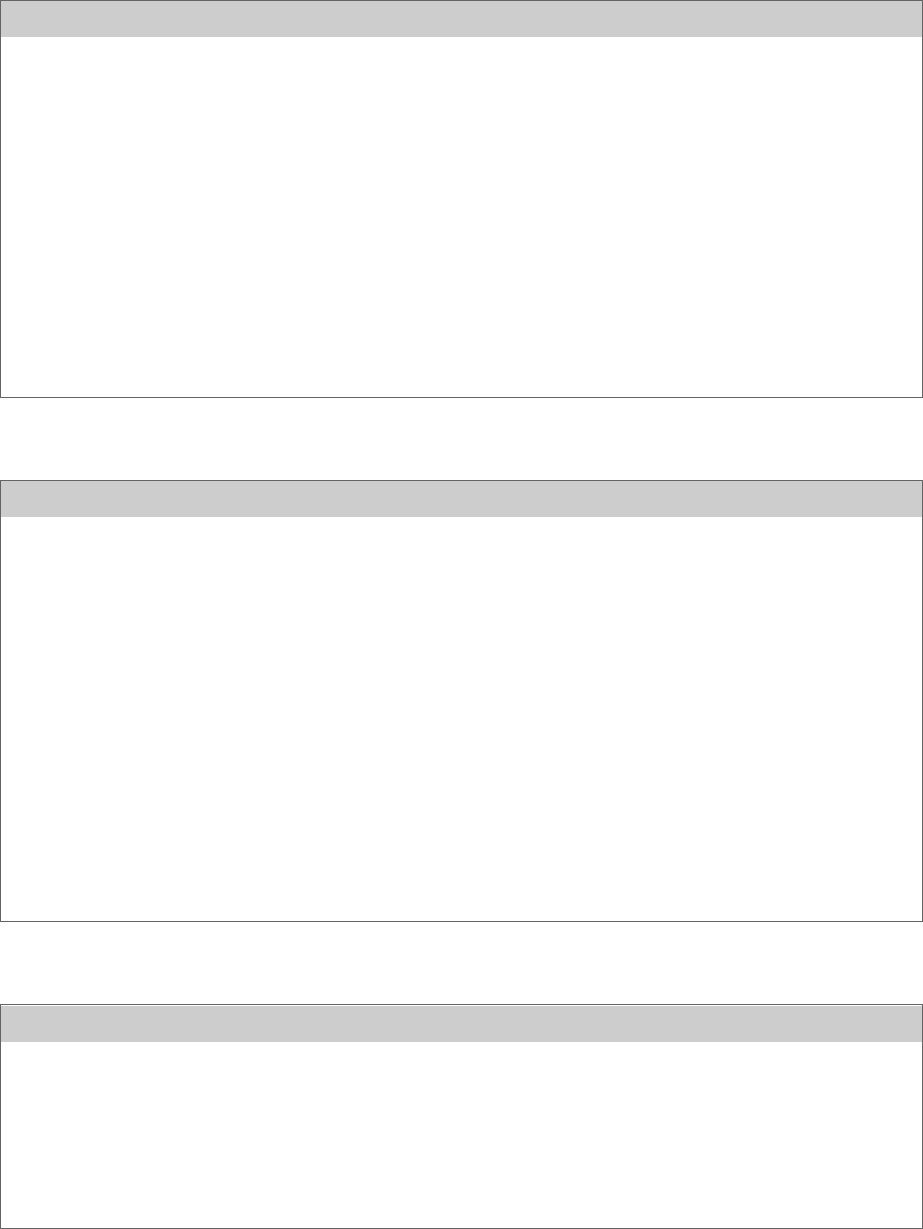

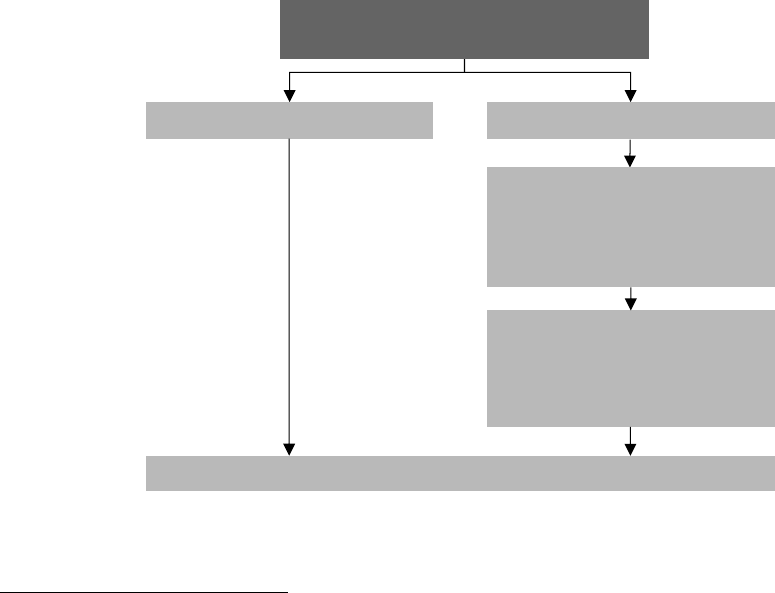

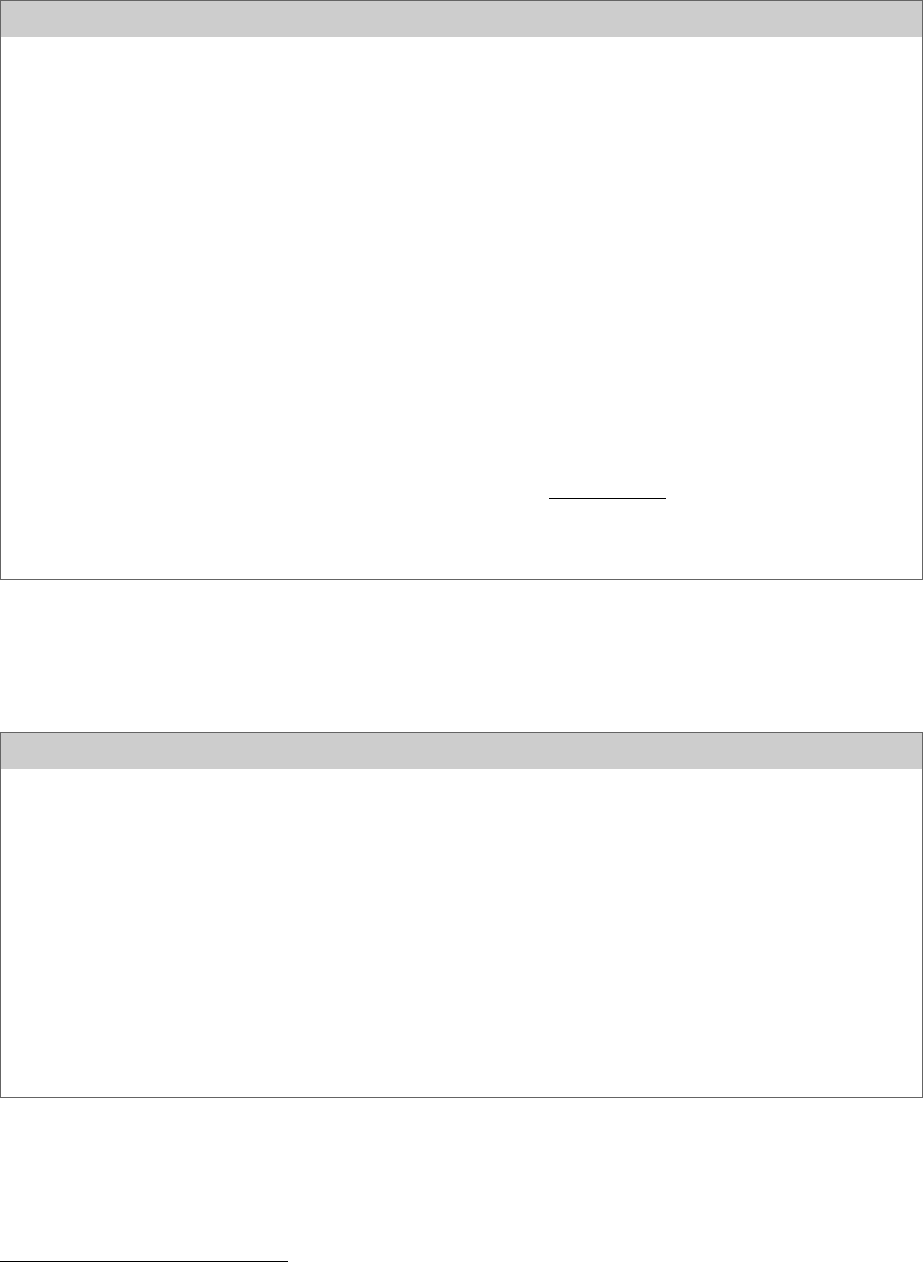

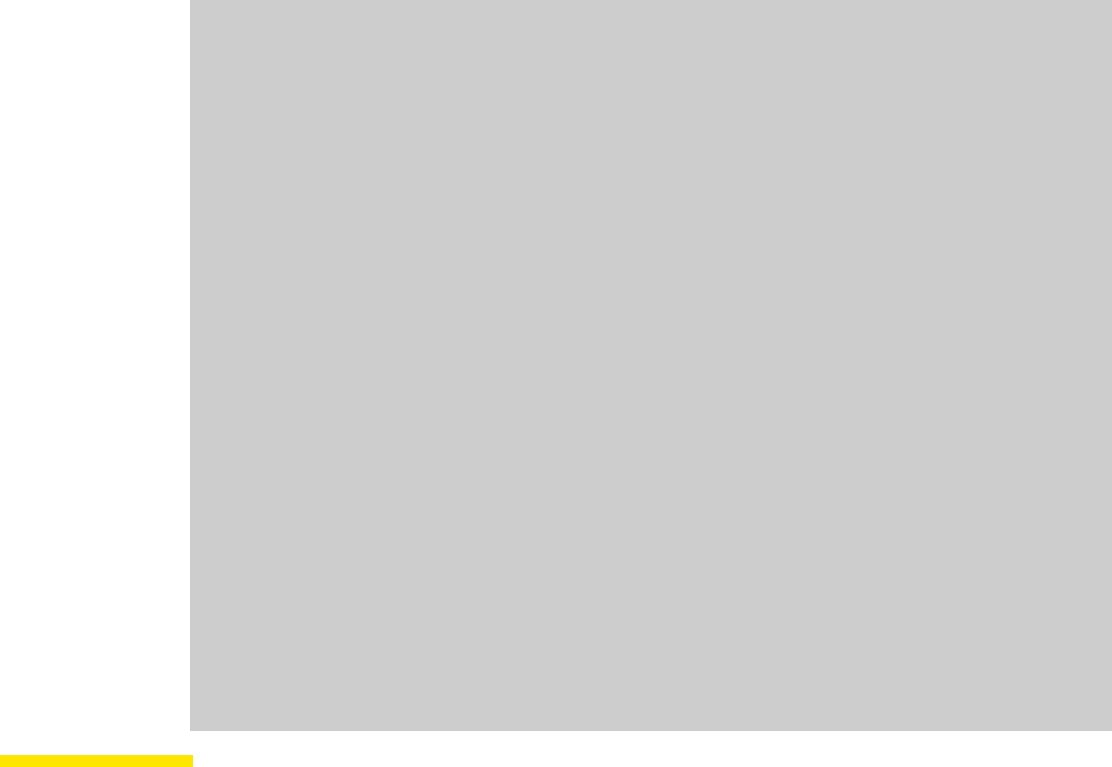

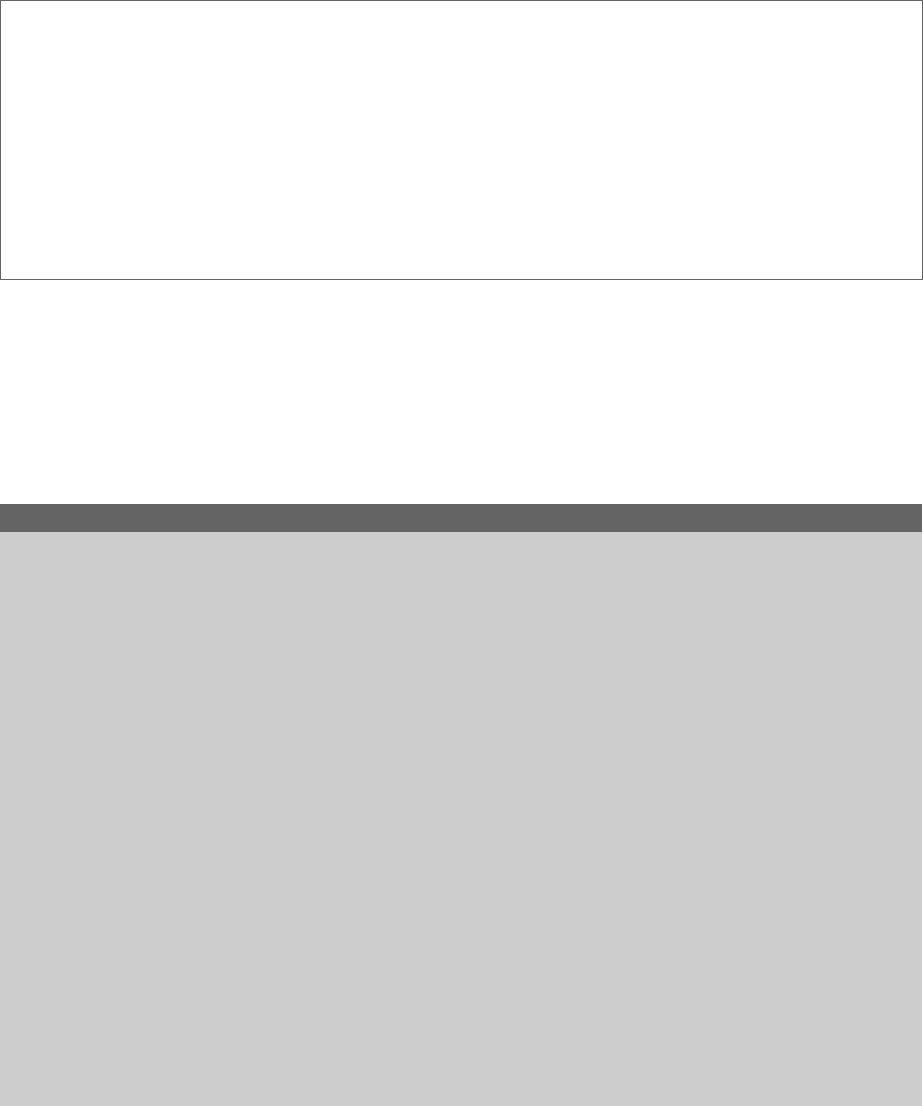

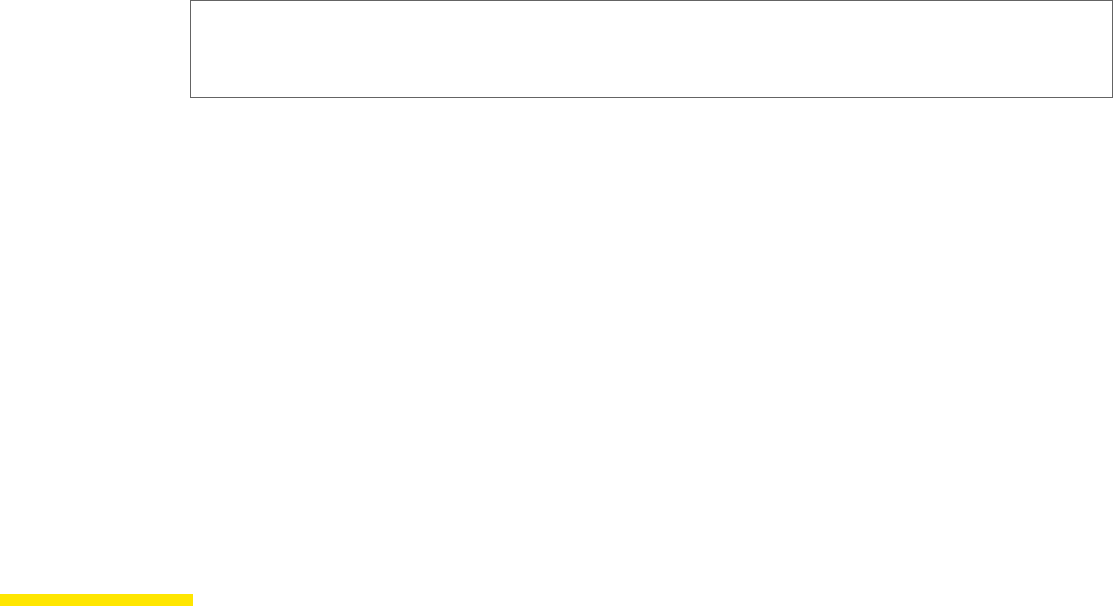

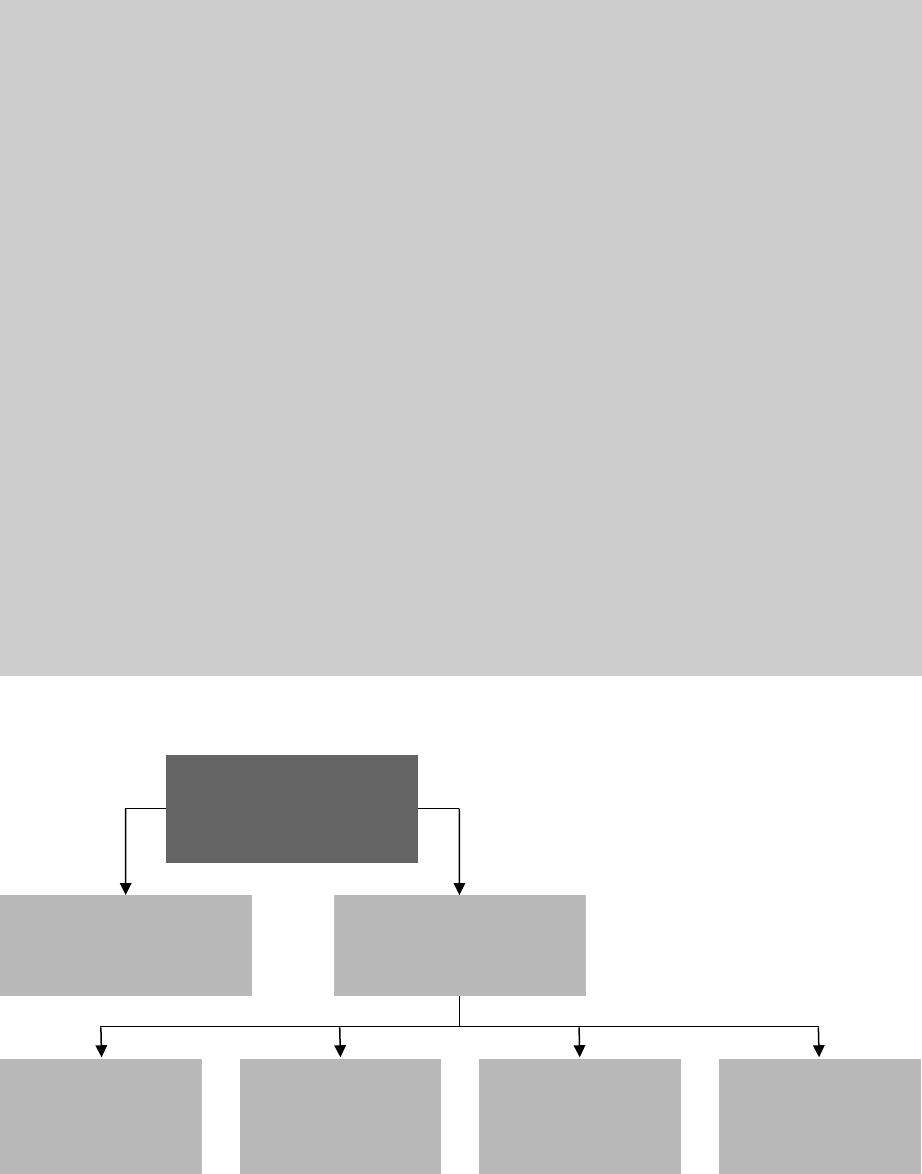

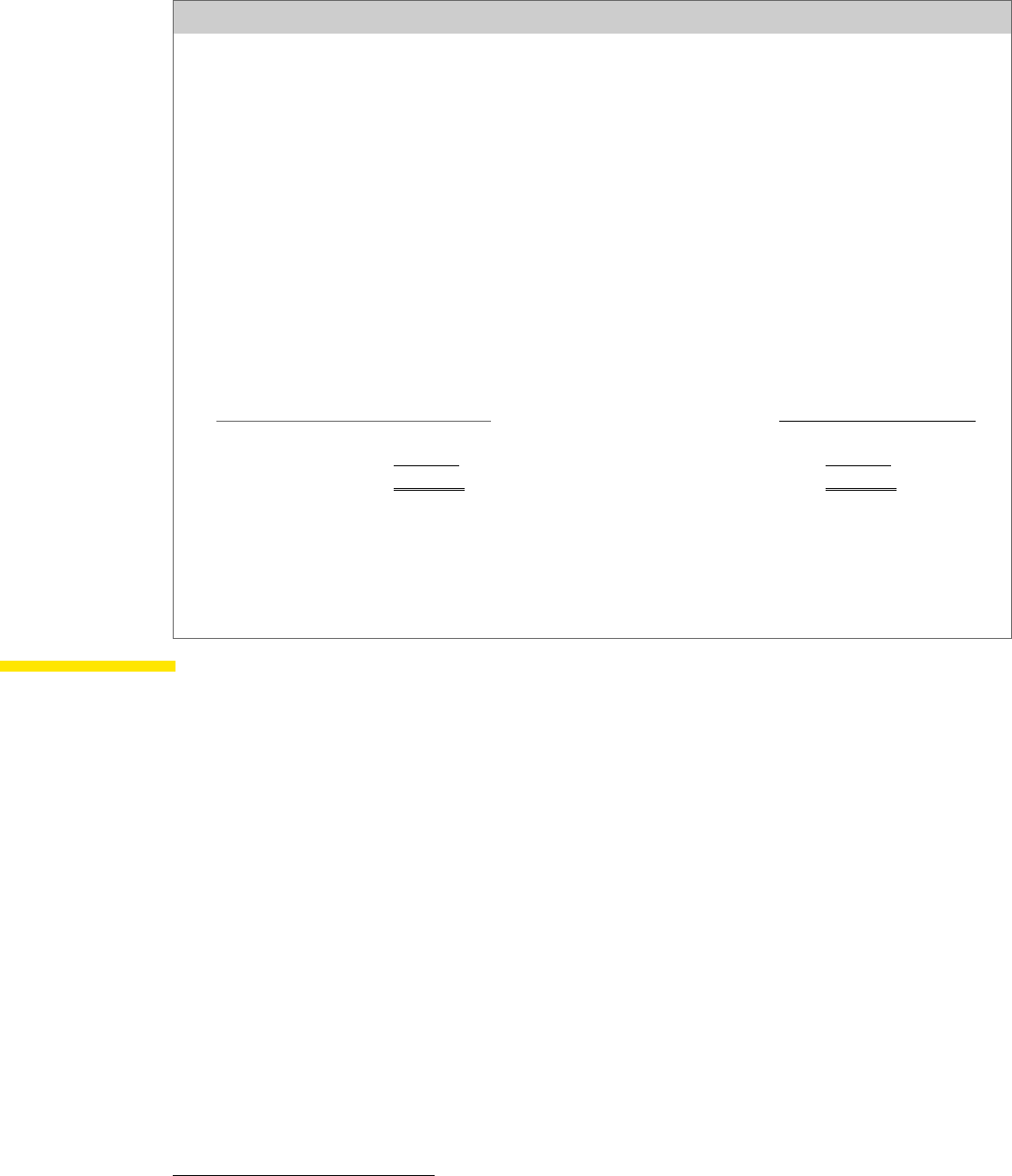

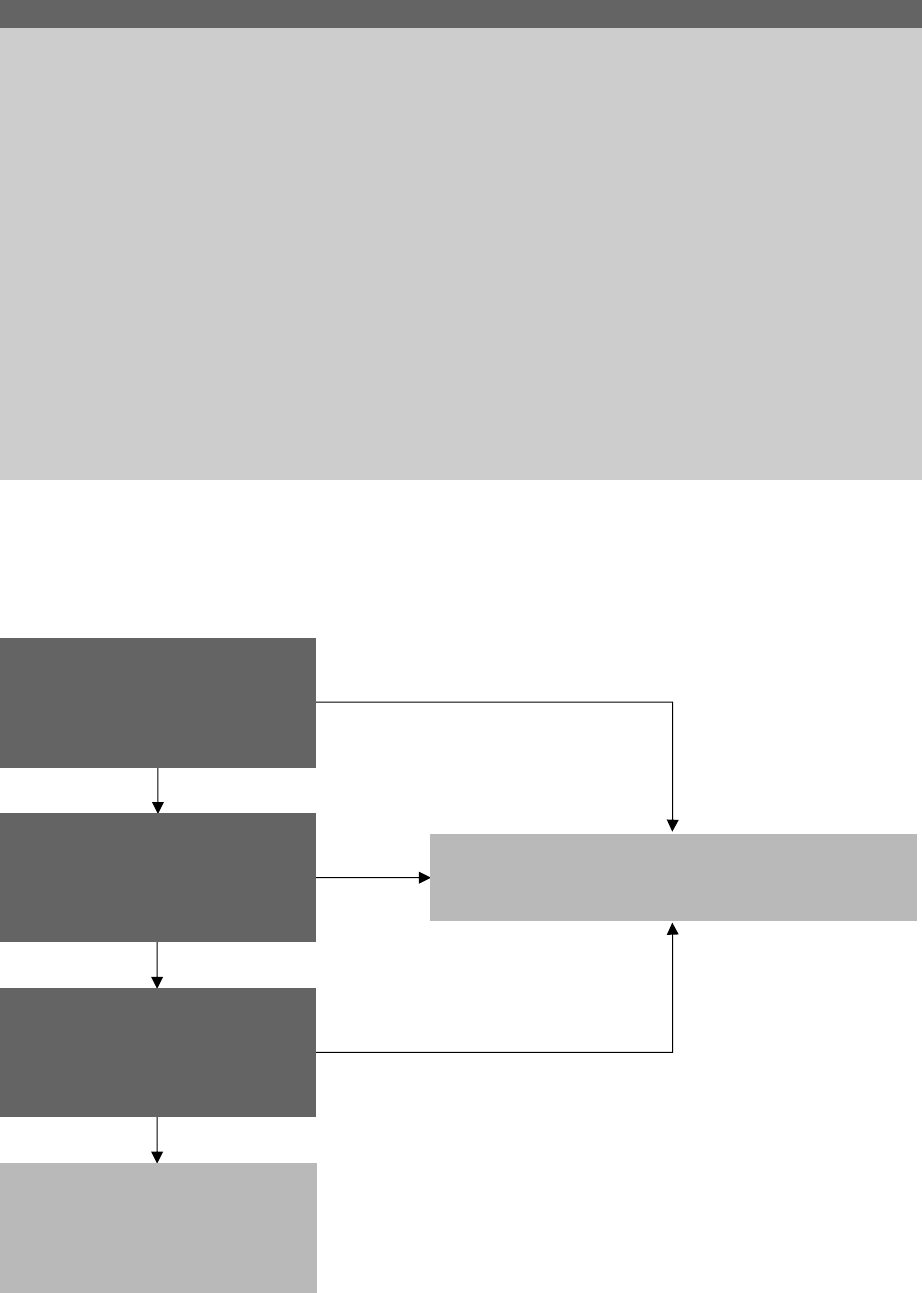

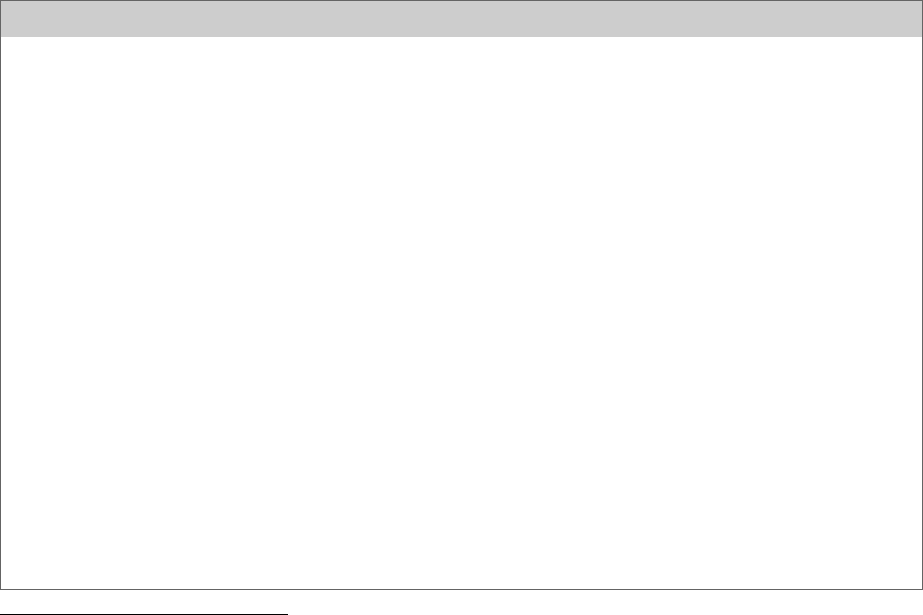

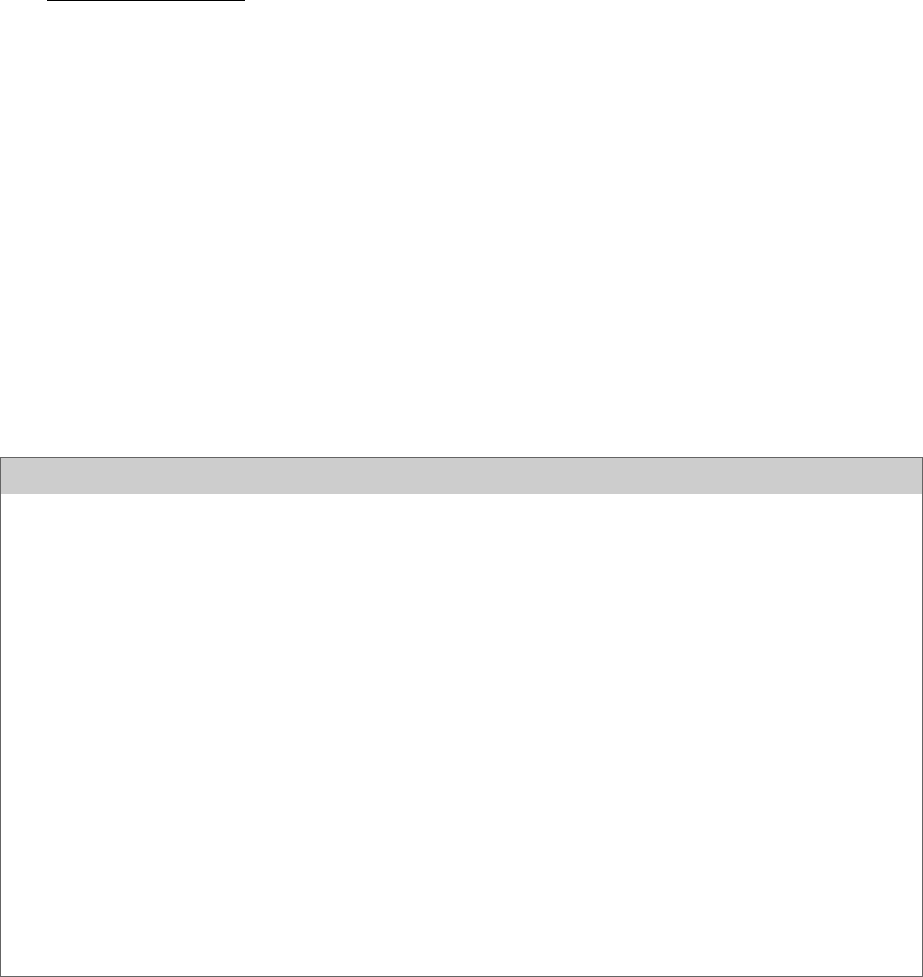

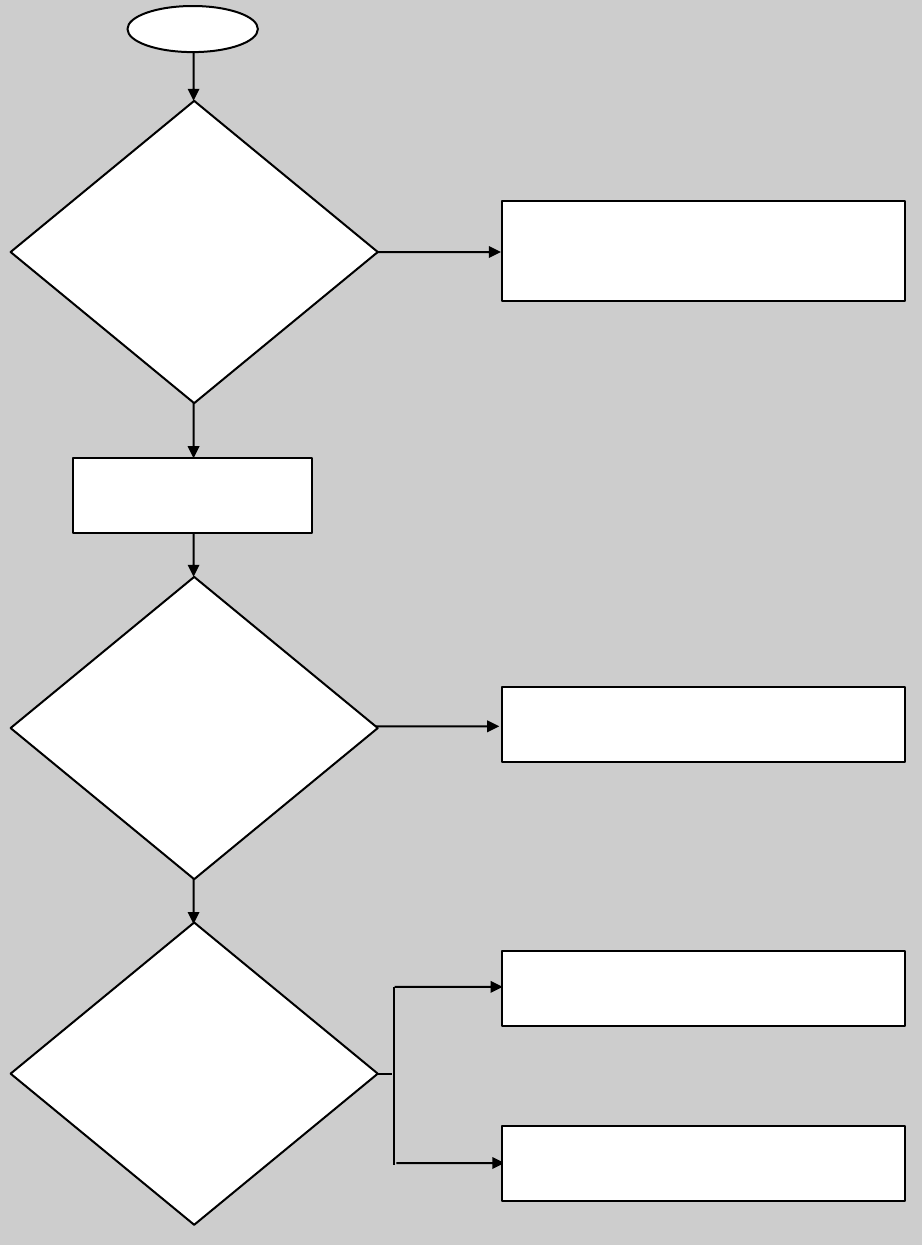

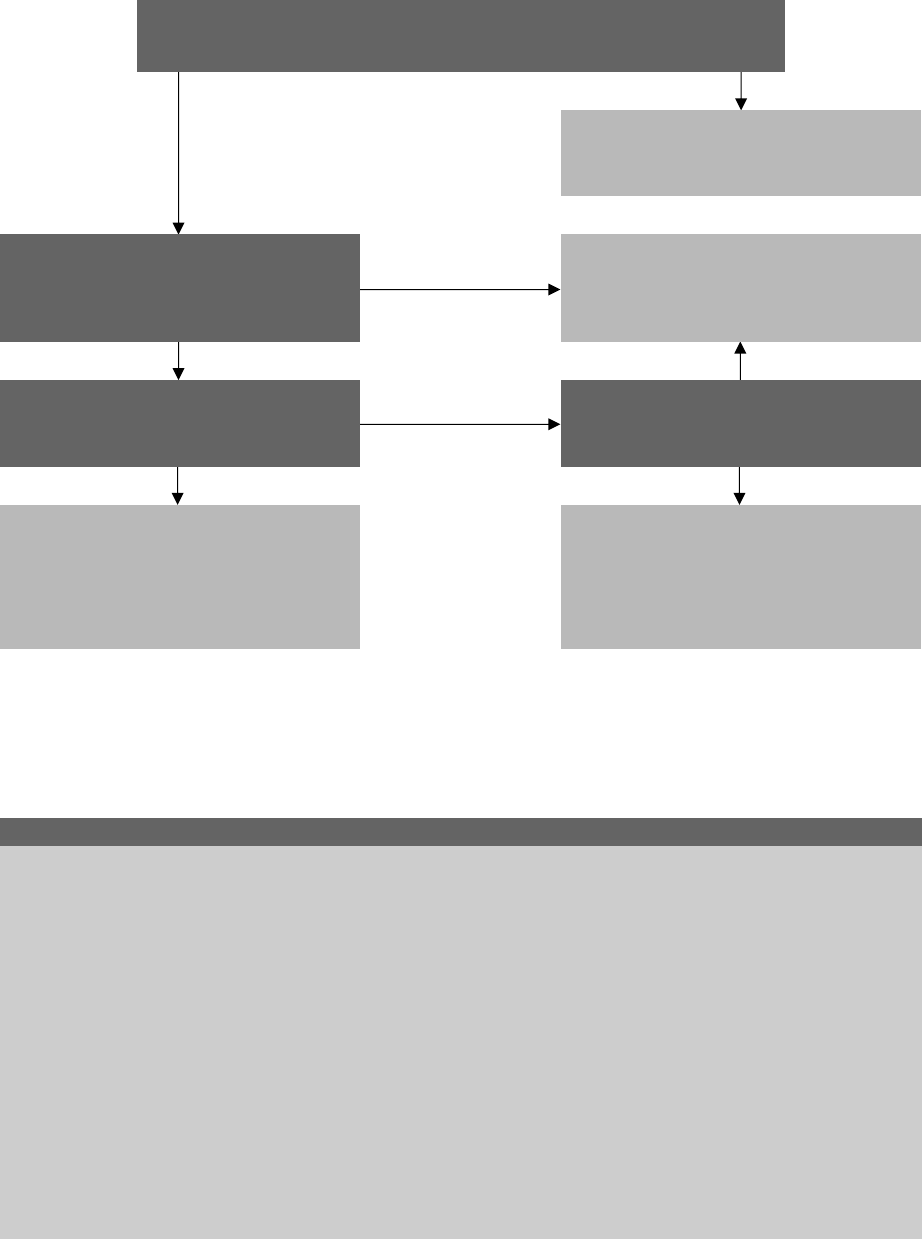

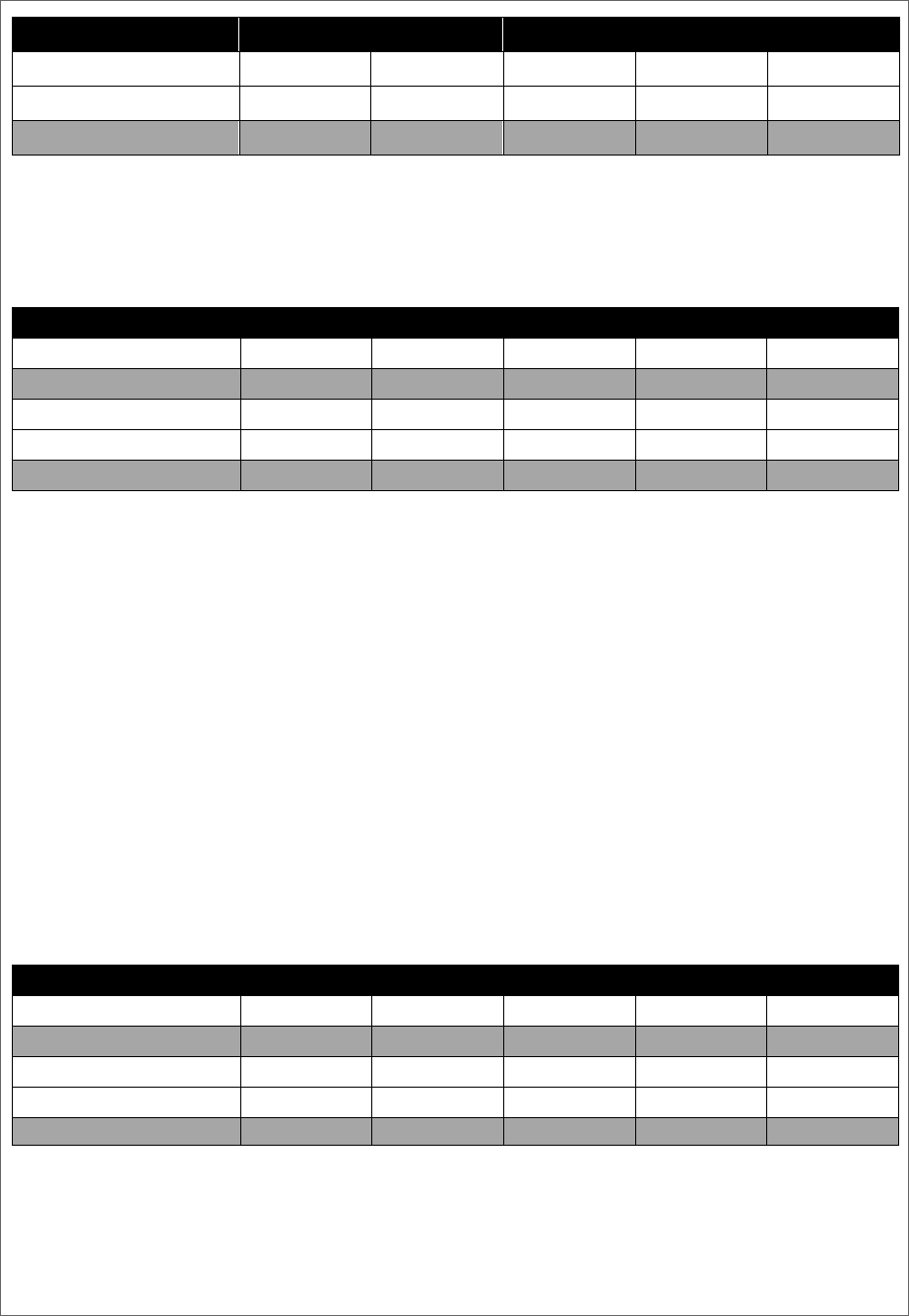

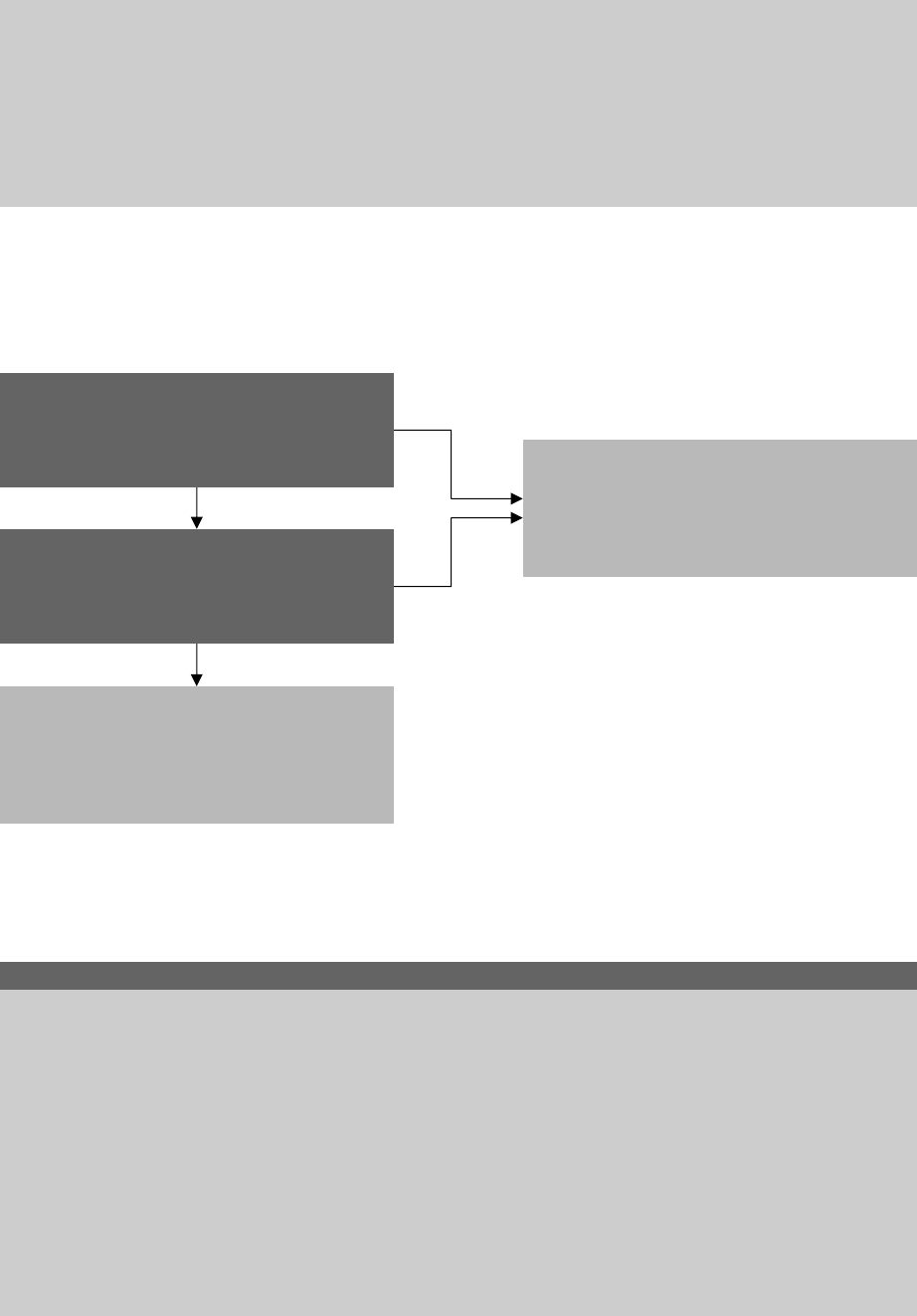

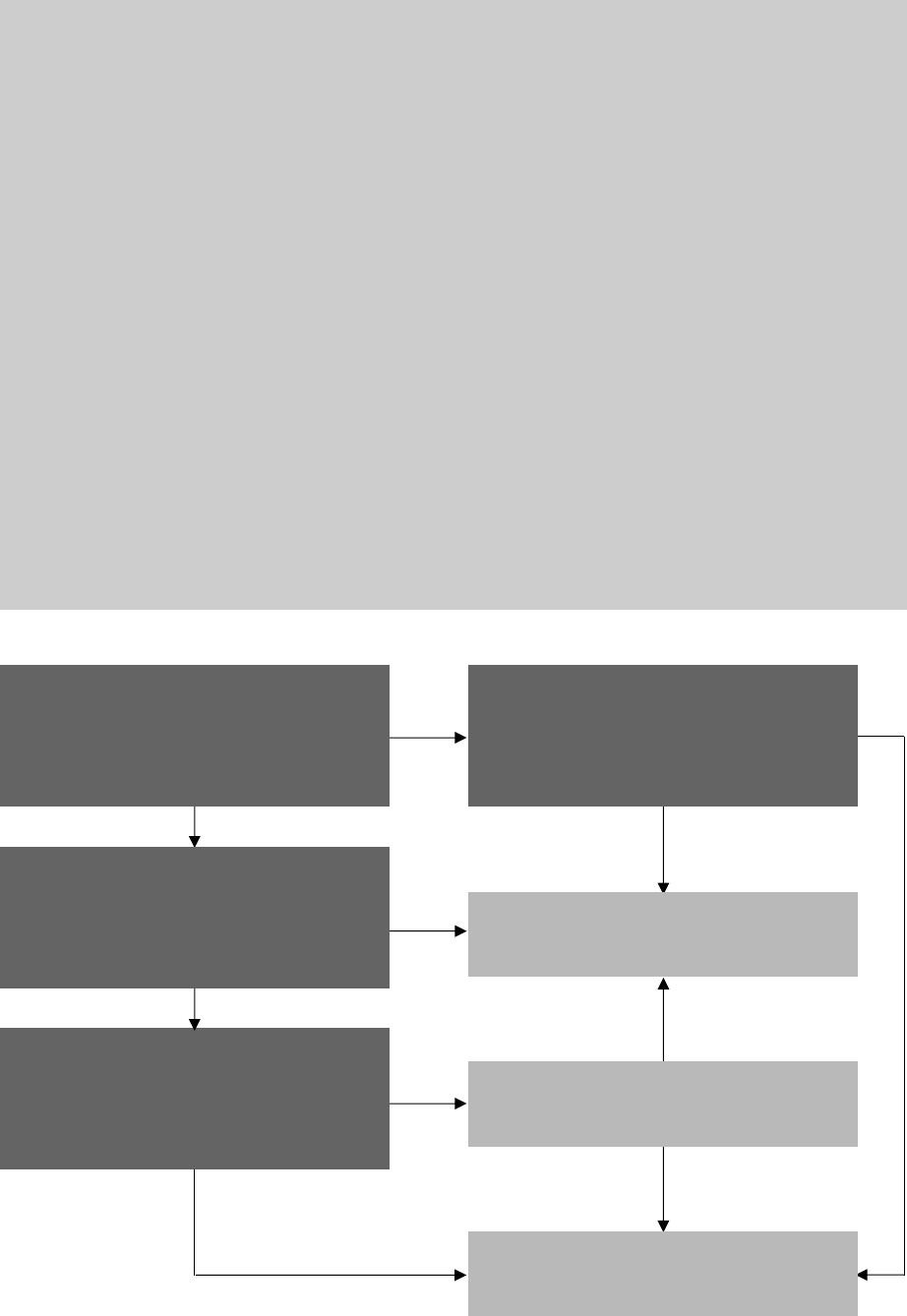

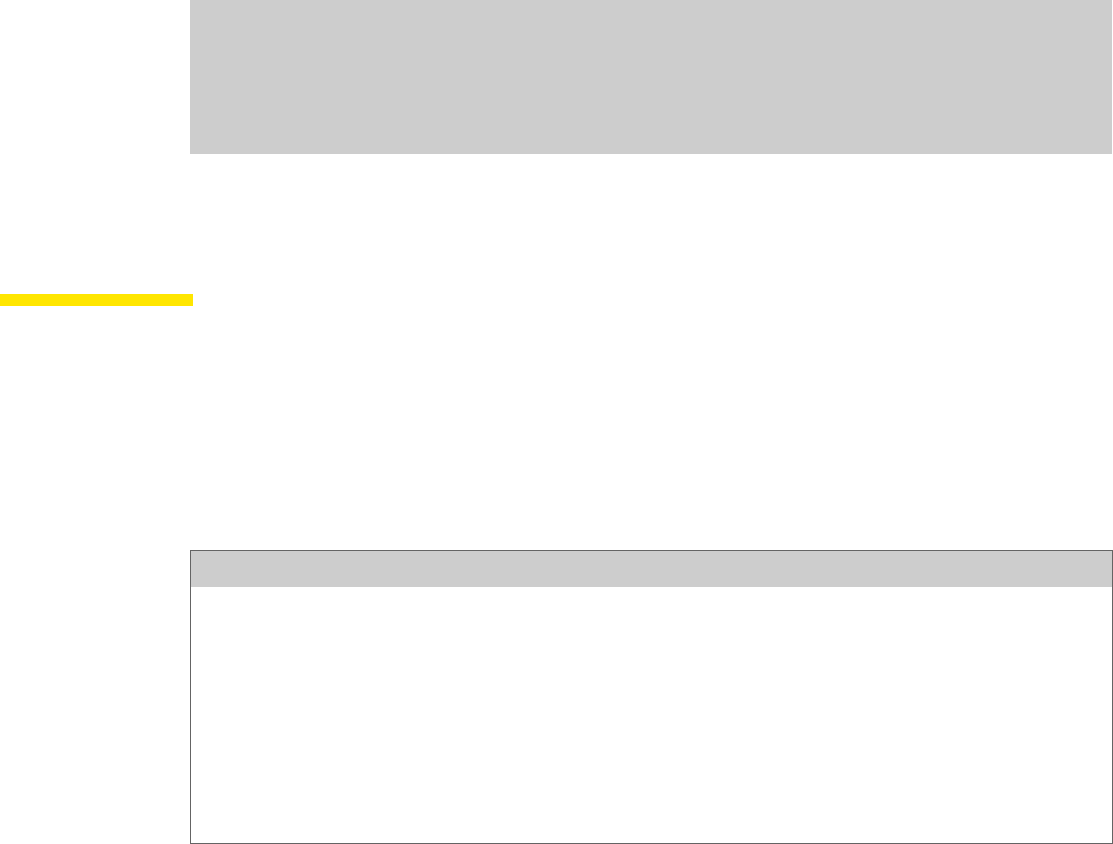

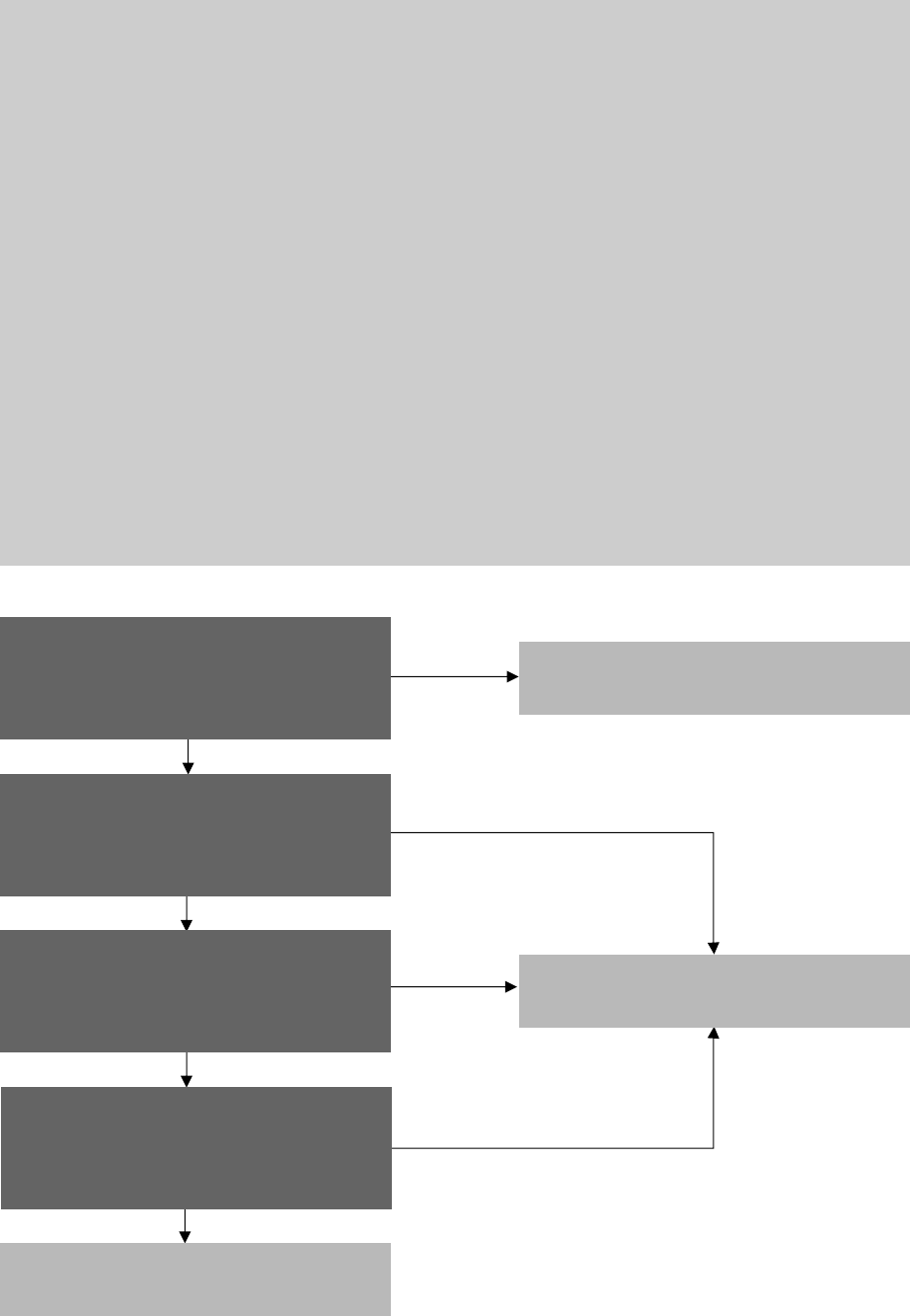

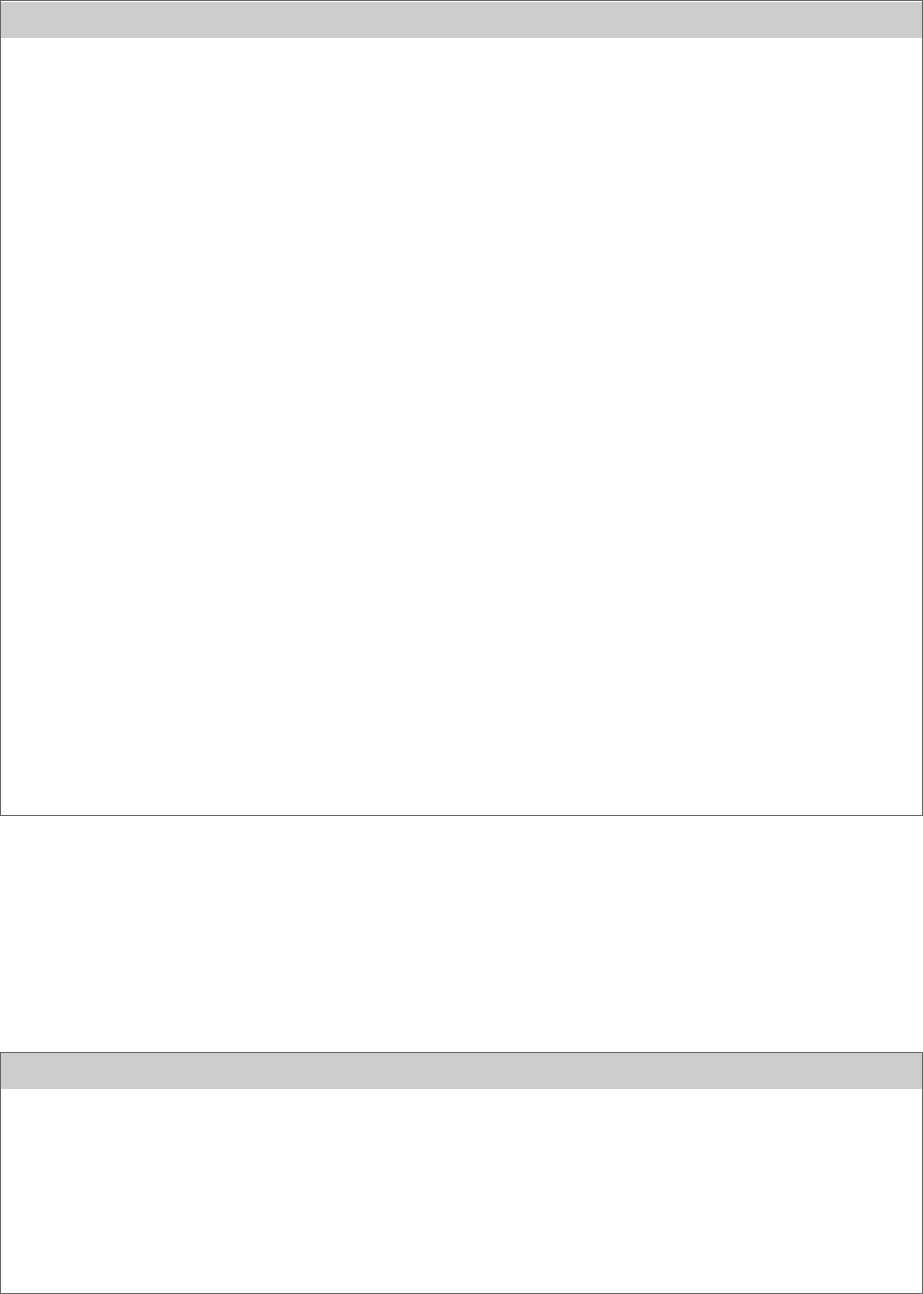

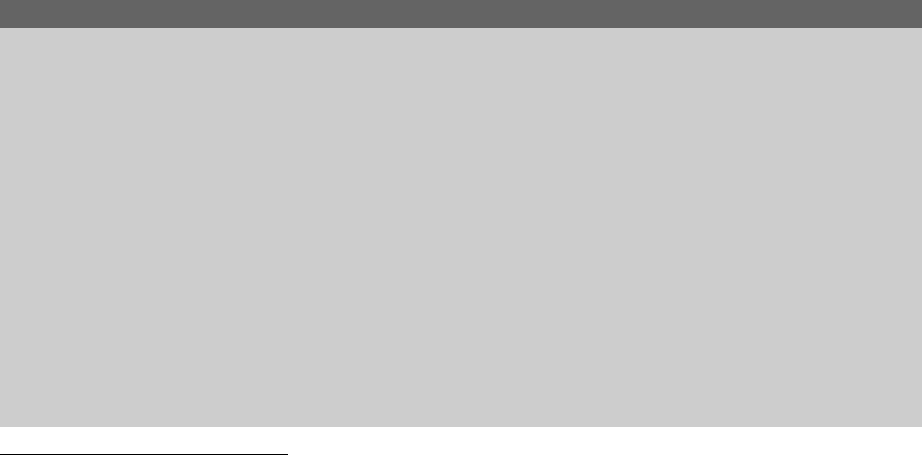

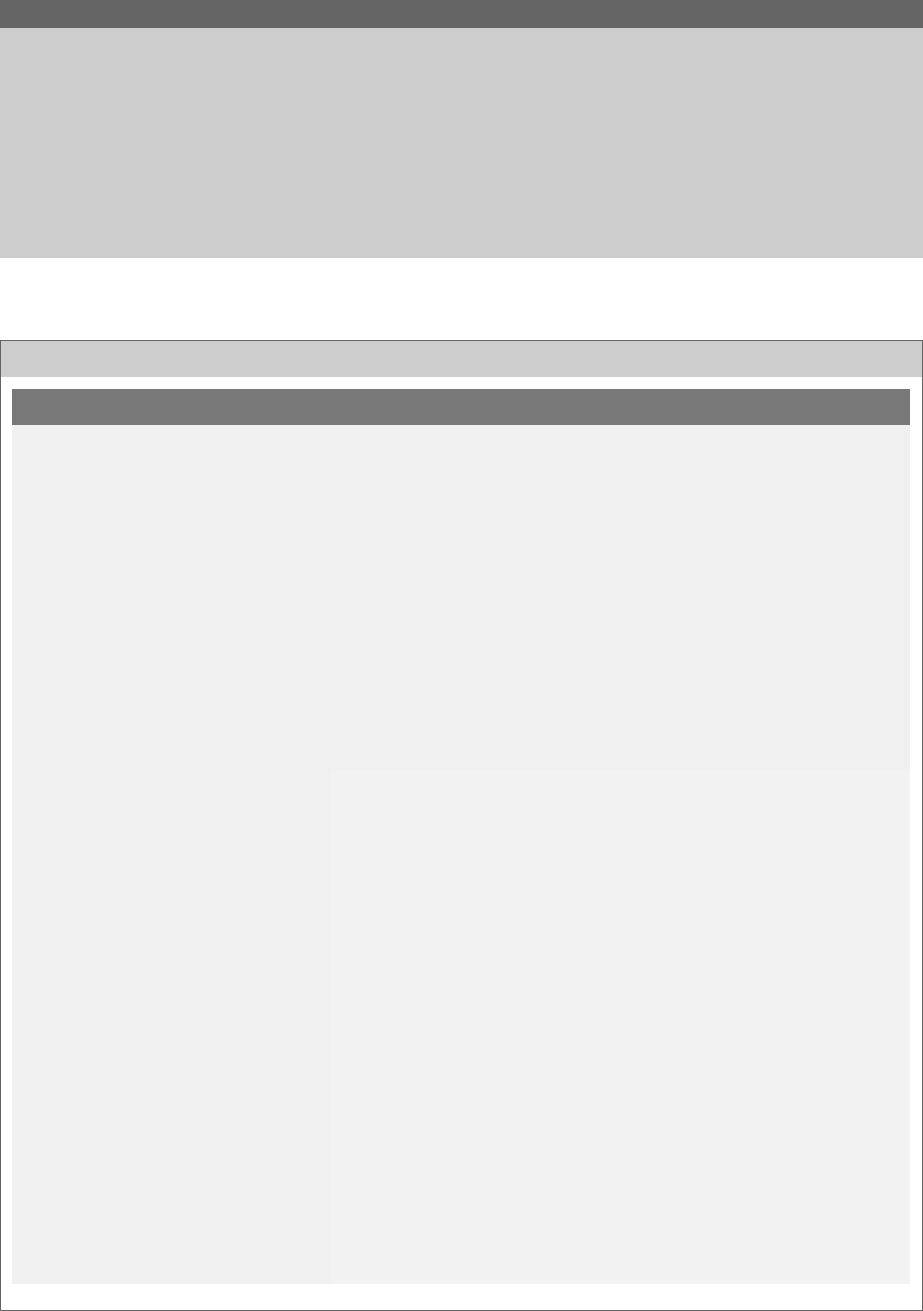

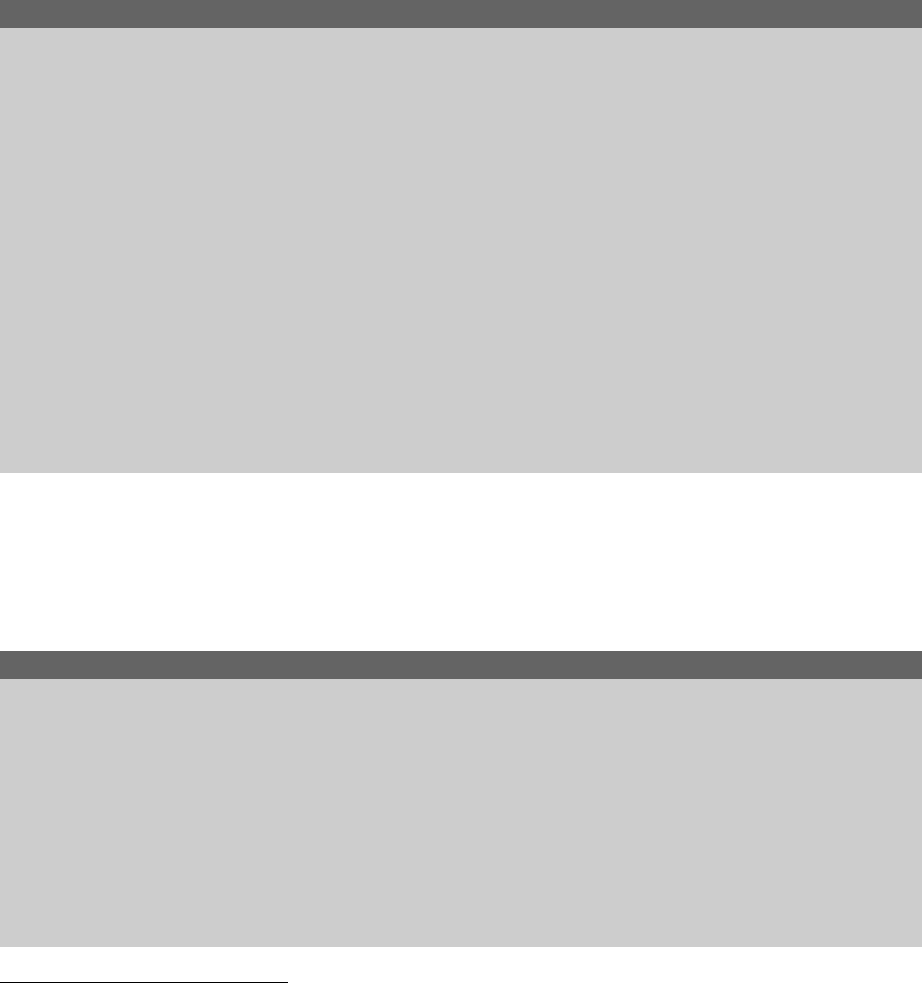

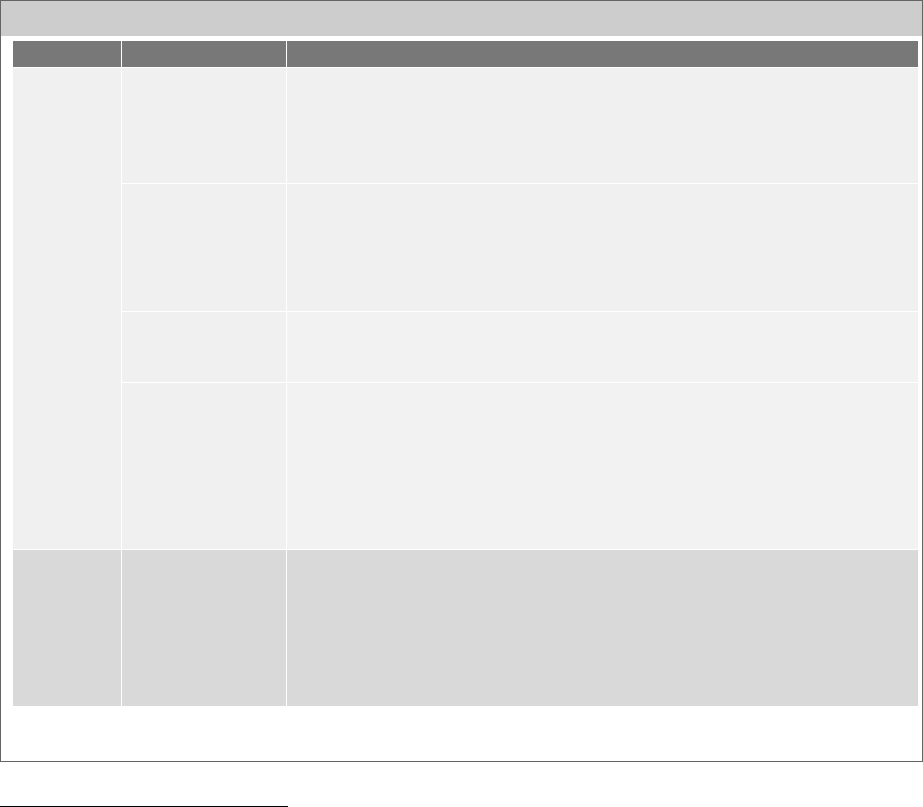

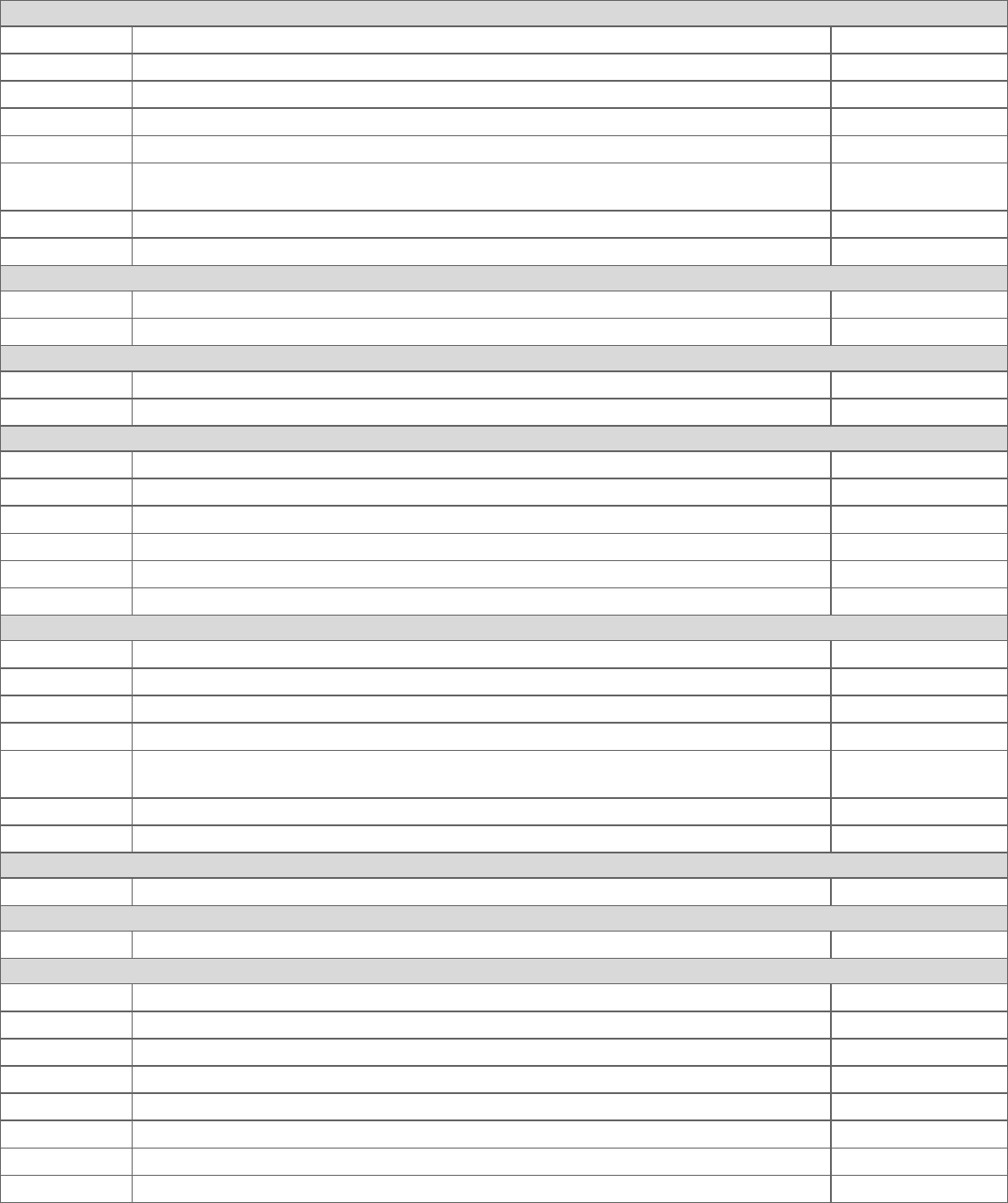

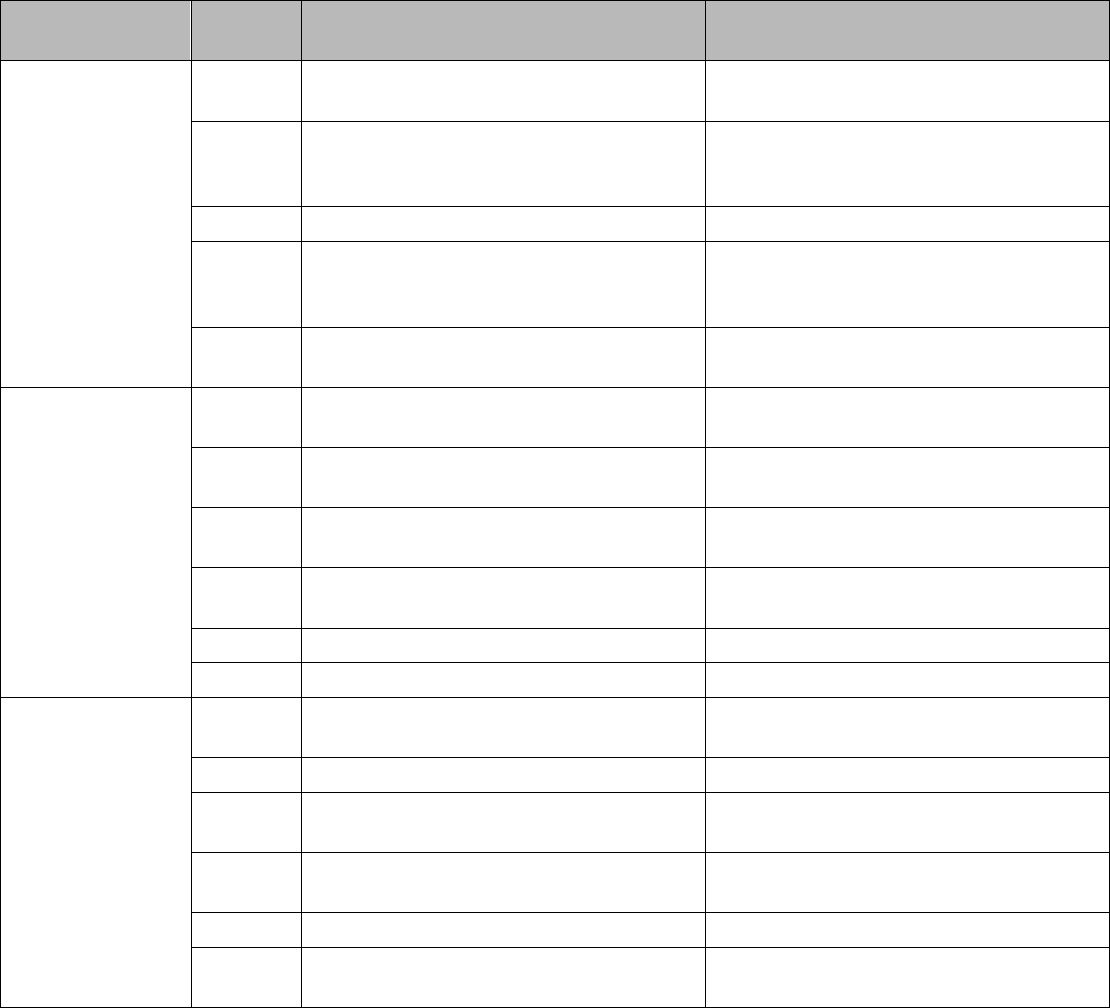

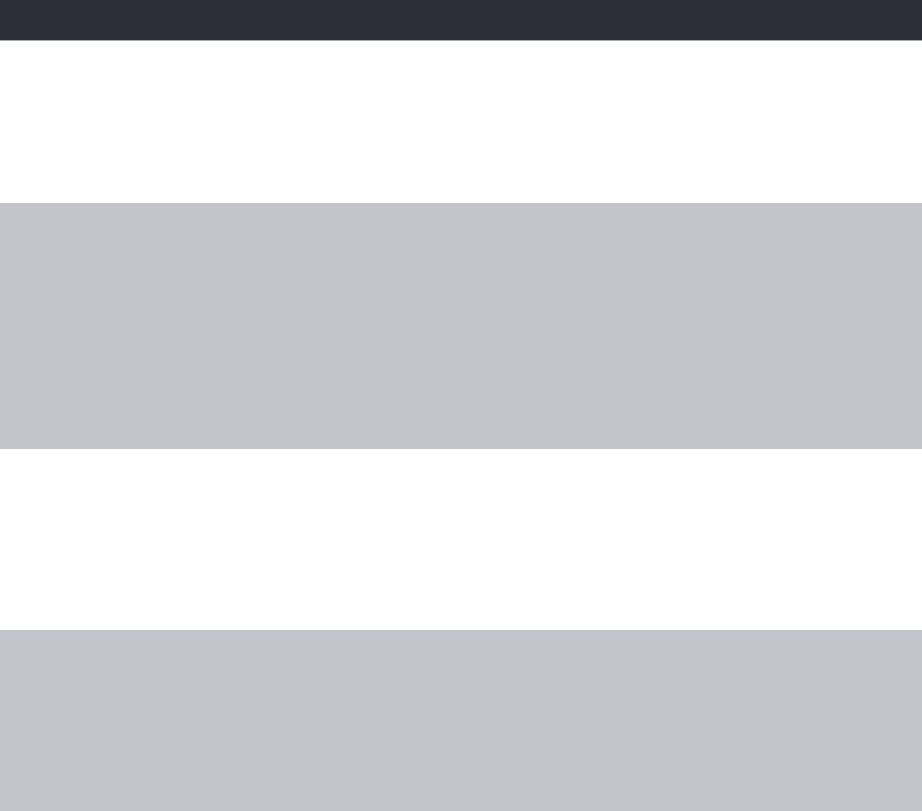

The following flowchart illustrates the guidance for identifying applicable accounting guidance for

collaborative arrangements:

* This includes units of account that are partially but not entirely with a customer. (ASC 808-10-15-5B)

No

Yes

No

No

No

Yes

Apply ASC 606 if the contract is with a

customer or another Topic if the contract

is not with a customer.

Yes

Does the arrangement meet the definition of a

collaborative arrangement as defined in

ASC 808-10-20? (ASC 808-10-15-2)

Apply other Topics, including ASC 606 to any

part (or parts) of the contract in its scope.

Account for transactions in collaborative

arrangements that are outside the scope of other

Topics, including ASC 606, based on an analogy

to authoritative accounting literature or, if there

is no appropriate analogy, a reasonable,

rational and consistently applied accounting

policy election. (ASC 808-10-15-5C)

Does the arrangement have a unit of account,

identified as a promised good or service (or

bundle of goods or services) that is distinct

using the guidance in ASC 606-10-25-19

through 25-22, that is at least partially with

a customer? (ASC 808-10-15-5B)

Yes

Apply ASC 606 to the unit of account

(i.e., including recognition, measurement,

presentation and disclosure guidance).

(ASC 808-10-15-5B)

Is the counterparty a customer for any units of

account in their entirety? (ASC 808-10-15-5B)

Account for transactions in collaborative

arrangements that are outside the scope of

other guidance,* including ASC 606, based on an

analogy to authoritative accounting literature or,

if there is no appropriate analogy, a reasonable,

rational and consistently applied accounting

policy election. (ASC 808-10-15-5C)

Yes

Is the arrangement entirely in the scope of ASC 606 or another Topic (i.e., other than ASC 808)? (ASC 808-10-15-3)

2 Scope

Financial reporting developments Revenue from contracts with customers (ASC 606) | 14

Consider the following example:

Illustration 2-4: Collaborative arrangements in the scope of ASC 606

Biotech and Pharma enter into an arrangement to jointly develop a drug candidate. Biotech agrees to

provide a license of intellectual property to the drug molecule and to develop the drug candidate in

exchange for a fee from Pharma. Both parties will participate in and share the costs of the research

and development (R&D) activities.

Analysis

Biotech determines that the arrangement is in the scope of ASC 808. To determine whether any of the

transactions in the arrangement are in the scope of ASC 606, it evaluates whether Pharma is a customer

for any aspect of the arrangement. Biotech determines that providing a license of intellectual property

is part of its ordinary activities but providing R&D activities in the context of this collaboration is not.

Therefore, Pharma is its customer only for the license transaction.

Biotech then applies the unit-of-account guidance (i.e., Step 2) in ASC 606-10-25-19 through 25-22 (see

section 4.2) and determines that the license of intellectual property is distinct from the R&D activities. Because

the license is a distinct unit of account in a transaction with a customer, Biotech accounts for the license of

intellectual property under ASC 606. Consistent with its past practices, Biotech accounts for amounts received

from Pharma for the R&D activities as contra-R&D expense (i.e., outside of ASC 606 revenue).

If Biotech had determined that the license of intellectual property and the R&D activities were a

combined unit of account, that entire unit of account would be outside the scope of ASC 606 because

it would include transactions that are with a customer and others that are not with a customer.

How we see it

Determining whether the counterparty to a collaborative arrangement is a customer for one or more

components of the arrangement may require significant judgment, and neither ASC 606 nor ASC 808

provide any additional considerations for how to make this evaluation.

2.4 Interaction with other guidance (updated September 2022)

The standard provides guidance for arrangements partially in its scope and partially in the scope of other

standards as follows.

Excerpt from Accounting Standards Codification

Revenue from Contracts with Customers — Overall

Scope and Scope Exceptions

Transactions

606-10-15-4

A contract with a customer may be partially within the scope of this Topic and partially within the

scope of other Topics listed in paragraph 606-10-15-2.

a. If the other Topics specify how to separate and/or initially measure one or more parts of the

contract, then an entity shall first apply the separation and/or measurement guidance in those

Topics. An entity shall exclude from the transaction price the amount of the part (or parts) of the

contract that are initially measured in accordance with other Topics and shall apply paragraphs

606-10-32-28 through 32-41 to allocate the amount of the transaction price that remains (if

any) to each performance obligation within the scope of this Topic and to any other parts of the

contract identified by paragraph 606-10-15-4(b).

2 Scope

Financial reporting developments Revenue from contracts with customers (ASC 606) | 15