WORKING PAPER

Bioterrorism and

Biocrimes

The Illicit Use of Biological

Agents Since 1900

W. Seth Carus

August 1998

(February 2001 Revision)

Center for Counterproliferation Research

National Defense University

Washington, D.C.

ii

Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied

within are solely those of the author, and do not necessarily represent the

views of the National Defense University, the Department of Defense, or any

other U.S. Government agency.

This study documents numerous instances in which someone claimed

that individuals or groups engaged in criminal conduct. The sources of the

allegations are documented in the text. Every effort has been made to

distinguish between instances in which the alleged conduct led to criminal

convictions and those that were never authoritatively proven.

This is a work in progress. The author welcomes comments,

especially those that correct errors, identify additional cases for research, or

identify additional sources of information on any of the existing cases.

Because additional research can change conclusions based on this data, the

author encourages readers to contact him before they use of any of the data

discussed in this manuscript. Please direct comments to the following

address:

Dr. W. Seth Carus

Center for Counterproliferation Research

National Defense University

Fort McNair, Building 62, Room 211

Washington, D.C. 20319-6000

Voice: 202-685-2242

Fax: 202-685-2264

E-mail: [email protected]

iii

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS..........................................................................................................................III

PREFACE..............................................................................................................................................V

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS......................................................................................................................VII

PART I: BIOTERRORISM IN PERSPECTIVE............................................................................... 1

CHAPTER 1 : INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................... 3

What is Bioterrorism?.................................................................................................................... 3

Studying Bioterrorism .................................................................................................................... 4

CHAPTER 2 : THE PRACTICE................................................................................................................ 7

Experience of Bioterrorism............................................................................................................ 7

Trends in Bioterrorism................................................................................................................. 10

Acquiring Biological Agents ........................................................................................................ 12

Employing Biological Agents....................................................................................................... 16

CHAPTER 3 : THE PRACTITIONERS .................................................................................................... 25

Nature of the Perpetrators ........................................................................................................... 25

Terrorist Group Characteristics .................................................................................................. 27

Operational Considerations......................................................................................................... 31

PART II: CASES................................................................................................................................. 33

CHAPTER 4 : CASE DEFINITION ......................................................................................................... 35

Sources of information ................................................................................................................. 37

Assessing the data ........................................................................................................................ 38

Organization of cases................................................................................................................... 39

CHAPTER 5 : USE OF BIOLOGICAL AGENTS....................................................................................... 42

Confirmed Use.............................................................................................................................. 42

Probable or Possible Use............................................................................................................. 76

CHAPTER 6 : THREATENED USE ........................................................................................................ 95

Threatened Use (Probable or Known Possession)....................................................................... 95

Threatened Use (No Known Possession) ................................................................................... 104

Threatened Use (Anthrax Hoaxes)............................................................................................. 122

CHAPTER 7 : POSSESSION................................................................................................................ 151

Confirmed Possession ................................................................................................................ 151

Probable or Possible Possession ............................................................................................... 154

CHAPTER 8 : OTHER........................................................................................................................ 161

Possible Interest in Acquisition (No Known Possession)........................................................... 161

False cases and hoaxes .............................................................................................................. 167

APPENDIX A: LIST OF CASES .................................................................................................... 179

SOURCES.......................................................................................................................................... 199

INDEX .............................................................................................................................................. 205

ABOUT THE AUTHOR....................................................................................................................... 209

v

Preface

This is the eighth revision of a working paper on biological terrorism first released in August 1998.

The last version was released in April 2000. As with the earlier versions, it is an interim product of the research

conducted by the author into biological terrorism at the National Defense University’s Center for

Counterproliferation Research. It incorporates new cases identified through December 31, 2000, as well as a

considerable amount of new material on older cases acquired since publication of the previous revision.

The working paper is divided into two main parts. The first part is a descriptive analysis of the illicit

use of biological agents by criminals and terrorists. It draws on a series of case studies documented in the

second part. The case studies describe every instance identifiable in open source materials in which a

perpetrator used, acquired, or threatened to use a biological agent. While the inventory of cases is clearly

incomplete, it provides an empirical basis for addressing a number of important questions relating to both

biocrimes and bioterrorism. This material should enable policymakers concerned with bioterrorism to make

more informed decisions.

In the course of this project, the author has researched over 270 alleged cases involving biological

agents. This includes all incidents found in open sources that allegedly occurred during the 20

th

Century. While

the list is certainly not complete, it provides the most comprehensive existing unclassified coverage of

instances of illicit use of biological agents. Research into the cases is ongoing, and additional information will

be incorporated as further information is uncovered.

vii

Acknowledgements

This working paper could not have been prepared without the assistance of a large number Most

important were my colleagues at the Center for Counterproliferation Research at the National Defense

University. Ambassador Robert Joseph, director of the Center when the bulk of the work was conducted,

provided the author with the opportunity to work at the Center, which provided the time needed to research and

write this manuscript. He showed extraordinary forbearance and support for this project. In addition, his

careful editing substantially strengthened the manuscript.

Writing this study would have been impossible without the expert guidance provided by many people

who took the time to explain the arcana of biological warfare. To all of them, I express my appreciation. In

particular, I have benefited from the willingness of several people who have had first hand experience in the

development of biological agents to spend time explaining the esoteric art of biological warfare. This includes

the late Thomas Dashiell, William J. Patrick III, and Ken Alibek.

Detailed research into two of the bioterrorism incidents was supported in part by Jonathan Tucker and

the Monterey Institute for International Studies. Case studies based on that research were published in Jonathan

B. Tucker, editor, Toxic Terror: Assessing Terrorist Use of Chemical and Biological Agents (Cambridge,

Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2000). In addition, the author benefited considerably from interactions with his

fellow authors, although the conclusions reached here sometimes differ from theirs.

The author is grateful for the assistance provided by the staff of the National Defense University

Library. In particular, the author is indebted to Jeannemarie Faison, Lorna Dodt, and Bruce Thornlow for their

expertise in performing electronic searches. Especially appreciated is the expert assistance of Katrina Elledge

provided valuable research assistance while serving as an intern at the Counterproliferation Center.

A considerable number of people have provided useful suggestions that corrected errors and otherwise

improved the manuscript. My thanks to Kathleen Bailey, Ph.D., Gordon Burck, LTC George W. Christopher,

USAF, MC, Joseph Goldberg, Ph.D., Ambassador Read Hanmer, Dave Huxsoll, D.V.M., Ph.D., Noreen A.

Hynes, M.D., M.P.H., Ambassador Robert Joseph, Ph.D., Shellie A. Kolavic, DDS, Cornelius G. McWright,

Ph.D., Dennis Perrotta, Ph.D., and Brad Roberts, Ph.D. I am indebted to them all. Any remaining errors are the

fault of the author.

Finally, the research and writing of this study was guided in many ways, more than she may realize,

by the sage advice and expert assistance of my wife, Noreen.

viii

PART I:

BIOTERRORISM IN

PERSPECTIVE

2

3

Chapter 1:

Introduction

During the past five years, the threat of bioterrorism has become a subject of widespread concern.

Journalists, academics, and policy analysts have considered the subject, and in most cases found much to alarm

them. Most significantly, it has captured the attention of policy makers at all levels of government in the

United States. Unfortunately, bioterrorism remains a poorly understood subject. Many policymakers and policy

analysts present apocalyptic visions of the threat, contending that it is only a matter of time before some

terrorist uses biological agents to cause mass casualties. In contrast, other analysts argue that the empirical

record provides no basis for concern, and thus largely dismiss the potential threat.

Neither approach is helpful. Imagining catastrophic threats inevitably leads to a requirement for

impossibly large response capabilities. In contrast, denying the potential danger altogether leads to the kind of

tunnel vision that led U.S. intelligence officials to totally ignore the emergence of Aum Shinrikyo in Japan,

despite its overtly hostile attitude towards the United States. This study takes an intermediate course. It

provides empirical evidence to support the views of those who argue that biological agents are difficult to use.

It also provides abundant evidence that some people have desired to inflict mass casualties on innocent

populations through employment of biological agents. Fortunately, these accounts also suggest that such

people lacked the capability to follow through with their plans. The research also casts considerable doubt on

our ability to predict which biological agents a perpetrator might employ. While some analysts assume that

terrorists will use those agents that proved of most interest to state weapons programs, bioterrorists and

biocriminals have acquired and used agents of little or no value as weapons of war. Ultimately, the evidence

supports the view that bioterrorism is a low probability, potentially high consequence event.

What is Bioterrorism?

There is no commonly accepted definition of bioterrorism. For purposes of this study, bioterrorism is

assumed to involve the threat or use of biological agents by individuals or groups motivated by political,

religious, ecological, or other ideological objectives. This definition, which emerged from the research

recorded in this volume, differs in several significant ways from many of the widely accepted definitions of

terrorism. Official definitions of terrorism generally emphasize that terrorism is intended to intimidate

governments or societies.

1

In essence, the core of terrorism is the ability to terrorize. The definition of

bioterrorism adopted here does not require such a motivation, although it also does not exclude it. A definition

that focuses on political intimidation fails to capture two significant motivations for bioterrorism.

First, some terrorists are attracted to biological weapons because they understand that pathogens could

cause mass casualties on an unprecedented scale. Official definitions appear to exclude groups with

apocalyptic visions who are uninterested in influencing governments and seek instead to inflict mass casualties.

Traditional terrorists use violence as a means to an end. In contrast, proponents of catastrophic terrorism view

mass killing as the desired end. Groups of this type are not common, yet they do exist.

Second, other terrorists are attracted to unique features of bioterrorism that have nothing to do with

the intended psychological impact of biological weapons use. They see biological agents as a tool for achieving

specialized objectives not necessarily intended to directly influence government actions. Virtually all

bioterrorists seek to keep their use of biological agents a secret, because in many instances success depended

on the lack of appreciation that a disease outbreak was intentional.

A bioterrorist can include any non-state actor who uses or threatens to use biological agents on behalf

of a political, religious, ecological, or other ideological cause without reference to its moral or political justice.

1

There are multiple definitions of terrorism. The Department of Defense defines terrorism as “the calculated use of violence or

threat of violence to inculcate fear; intended to coerce or to intimidate governments or societies in the pursuit of goals that are generally

political, religious, or ideological.” See Joint Publication 1-02, DOD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, as found at

http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/jel/doddict/. In contrast, the FBI defines terrorism as “the unlawful use of force or violence against persons or

property to intimidate or coerce a Government, the civilian population, or any segment thereof, in furtherance of political or social

objectives.” See Federal Bureau of Investigation, Terrorism in the United States 1995, as found at http://www.fbi.gov.

4

This includes non-state actors who operate in organized military units (as with guerillas) if biological agent use

was undertaken with covert, improvised delivery means.

Studying Bioterrorism

Despite all the attention devoted to bioterrorism, it remains surprisingly misunderstood. In part, this

reflects a lack of information about bioterrorism. Relatively little effort was devoted to its study, and the focus

of the small literature on the subject was largely theoretical.

2

Virtually nothing was written about past

examples of bioterrorism. Indeed, the first unclassified effort to systematically identify all bioterrorism

incidents was not conducted until 1995.

3

Given this apparent lack of interest, it is perhaps not surprising that

the first official account of the 1984 use of biological agents by the Rajneeshees was published only in 1997.

4

In the late 1990s, the gaps in our understanding of past terrorist interest in biological agents have been reduced

by several initiatives to explore the history of bioterrorism. The Monterey Institute for International Studies has

played a significant role in this process. It has created a comprehensive database of chemical and biological

terrorism incidents and has sponsored teams of scholars who have produced detailed case studies analyzing

terrorist resort to chemical and biological weapons.

5

In addition, several researchers have examined specific

instances of bioterrorism.

Study objectives

This volume reflects the result of a study initiated in early 1997 to address the lack of information

about bioterrorism. Part I provides a descriptive analysis of what is known about past instances of bioterrorism,

based on the comprehensive survey of all known bioterrorism incidents provided in Part II. Each of the

incidents included in Part II is described to the extent possible with the available information. In addition, the

data provided in this volume provides some insights useful for the debates about bioterrorism that erupted in

the late 1990s. In particular, it provides some insight into possible motivations for resort to bioterrorism and

the technical hurdles that face anyone attempting to use biological agents.

The result is a description and analysis of 54 alleged terrorist cases. The quality of the available

information, however, is such that only 27 of the cases can be substantiated.

6

Because it was clear that it would

be possible to identify few confirmed cases involving terrorist groups, the research included other types of

perpetrators, including criminals and covert use by governments.

7

These inclusions led to the addition of 82

criminal cases, of which there was confirmation on 56, and 113 cases where the perpetrators cannot be

characterized clearly as either criminals or terrorists (only 97 confirmed). Almost all of the confirmed cases

where a perpetrator cannot be identified are anthrax hoaxes. Most of these cases probably would be classified

as criminal incidents if more information about the perpetrators were available.

8

In addition, 20 of the cases

2

Among the past studies of bioterrorism are Jeffrey D. Simon, Terrorists and the Potential Use of Biological Weapons: A

Discussion of Possibilities, RAND report R-3771-AFMIC, December 1989, p. 8, Jessica Eve Stern, “Will Terrorists Turn to Poison?,”

Orbis, Vol. 37, No. 3 (Summer 1993), pp. 393-410, and Raymond Allan Zilinskas, “Terrorism and Biological Weapons: Inevitable

Alliance?,” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Autumn 1990), pp. 44-72. See also the essays in Brad Roberts, editor,

Terrorism with Chemical and Biological Weapons (Alexandria, Virginia: Chemical and Biological Arms Control Institute, 1997).

3

The major exception was the survey of bioterrorism incidents by Ron Purver, Chemical and Biological Terrorism: The Threat

According to the Open Literature, Canadian Security Intelligence Service, June 1995.

4

Thomas J. Török, et al., “A Large Community Outbreak of Salmonellosis Caused by Intentional Contamination of Restaurant

Salad Bars,” JAMA, August 6, 1997, pp. 389-395.

5

The case studies are contained in Jonathan B. Tucker, editor, Toxic Terror: Assessing Terrorist Use of Chemical and

Biological Agents (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2000). They provide a more detailed look at several of the cases included in this

volume. However, the conclusions in this volume sometimes differ from those of the authors of the Toxic Terror case studies..

6

The criteria for inclusion are discussed in Chapter 4, while the individual cases are described in Chapters 5 through 8. The

cases are listed in Appendix A.

7

Criminals are distinguished from terrorists by motivation and objective. Criminals are motivated by objectives such as

personal revenge or financial gain. They may be driven by psychological pathologies. They do not have larger ideological objectives.

8

In some instances, it is difficult to determine if perpetrators were motivated by political or criminal motivations. Several

perpetrators who tried to extort money from governments also made political demands. Since such political demands could have been a

cover for financial motivations, when little is known about the perpetrator’s true objectives it is impossible to determine whether an

incident should be considered terrorist or criminal. Some widely reported cases fall into this category. For example, Thomas Lavy, a

survivalist living in Arkansas, was arrested in 1995 on charges related to the possession of the toxin ricin. His motivations for acquiring the

ricin were never clarified before he committed suicide. Nor is it clear why Larry Wayne Harris purchased Yersinia pestis, the organism that

causes plague. Although Harris had links to white supremacist groups, including the Aryan Nation and the Christian Identity movement, he

5

involve allegations of covert state activities, although the evidence is compelling in only 11 of then. In all, 269

cases were researched involving allegations that terrorists, criminals, or covert state operators used, acquired,

threatened use, or took an interest in biological agents.

Although there are differences between terrorist and criminal uses of biological agents, the

biocriminal faces many of the same obstacles as the bioterrorist. Both must acquire, develop, and employ

biological weapons, so the technical constrains that appear in criminal cases are likely to apply for terrorist

cases. In addition, it is possible that criminal cases will be a leading indicator of possible terrorist interest in

biological agents. Nevertheless, the differences between terrorists and criminals suggest caution needs to be

exercised in extrapolating from the experience of criminals to that of terrorists.

claimed that the cultures were needed to support research on the development of medical treatments for the disease. The law enforcement

investigation uncovered no evidence that he had a more nefarious objective.

7

Chapter 2:

The Practice

The unique characteristics of biological agents make bioterrorism fundamentally different from other

forms of terrorism. Not only do biological agents differ radically from other weapons available to the terrorist,

but biological weapons also are substantially different from other weapons of mass destruction, such as

chemical and nuclear weapons. Assessing the prospects for bioterrorism requires an appreciation of how

biological agents can be acquired and how they are disseminated. Because terrorists are likely to be confronted

with many of the same obstacles faced by criminals in the acquisition and use of biological agents, both types

of actors are included in this discussion.

Experience of Bioterrorism

A starting point for evaluating the challenge posed by bioterrorism is an examination of the evidence

regarding the extent to which terrorists have used or thought about using biological agents. Some caution must

be exercised in evaluating the empirical data, because it is possible that future patterns will differ significantly

from past patterns of behavior. Hence, the following should be considered in the context of the subsequent

discussion of the factors that might affect the propensity of terrorists to resort to biological weapons.

Bioterrorism or Biocrimes

Interest in biological agents is not confined to groups with known political agendas. Indeed, most

individuals and groups who have used biological agents had traditional criminal motives. Hence, it is essential

to separate the clearly criminal perpetrators from those with political agendas, whether the motive is sectarian,

religious, or ecological. The available evidence, in fact, suggests that the vast majority of cases involve

criminal motives.

Extent of interest

To date, few terrorists have demonstrated an interest in bioterrorism, and fewer still tried to acquire

biological agents. As mentioned previously, open source accounts mention at least 54cases in which a terrorist

group allegedly had an interest in biological agents, but there is little evidence to confirm most of the cases.

Thus, there are only 27 cases in which there is more than minimal evidence that a terrorist group possessed,

attempted to acquire, threatened to use, or expressed interest in biological agents. Even in some of confirmed

cases, there is no way to determine the seriousness of the interest in biological agents. Terrorist groups

apparently acquired biological agents in only eight cases.

Terrorists have used biological agents, but rarely and with relatively little effect. A review of the cases

researched for this study confirms only five groups that used or tried to use biological agents. Although there

may be other examples that have never been publicly identified, only one of these cases is known to have

resulted in harm to people.

Rajneeshees: According to the FBI, there is only one instance in which a terrorist group operating in

the United States actually employed a chemical or biological agent.

9

This incident took place in September

1984. The perpetrators were members of the Rajneeshee, a religious cult that established a large commune in

Wasco County, a rural area east of Portland, Oregon. The Rajneeshees used Salmonella typhimurium, which

causes salmonellosis or food poisoning, to contaminate restaurant salad bars. An estimated 751 people became

ill because of that attack, including about 45 who were hospitalized. There were no fatalities. This is the only

bioterrorism incident in which human illness has been verified.

9

Testimony of John P. O’Neill, Supervisory Special Agent, Chief, Counterterrorism Section, Federal Bureau of Investigation,

p. 238, in Committee on Governmental Affairs, U.S. Senate, Global Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction, Part I.

8

Aum Shinrikyo: In addition to using sarin nerve gas in the Tokyo subway system, Aum Shinrikyo

produced biological agents and tried to use them. According to press reports, the Japanese police discovered

that the Aum’s membership included skilled scientists and technicians, including some with training in

microbiology. The Aum expressed an interest in several biological agents, allegedly including B. anthracis,

botulinum toxin, C. burnetii (Q-fever), and even Ebola. The Aum tried to disseminate biological agents,

including B. anthracis and botulinum toxin, but there is no evidence that they actually managed to produce any

pathogens or toxins. The group allegedly targeted the U.S. Navy base at Yokosuka in one of its attempted

attacks.

10

Dark Harvest: This little known group protested the continued anthrax contamination of Gruinard

Island, which is where the British military tested an anthrax bomb during World War Two. The group took

anthrax-contaminated soil, apparently from the island, and dumped it on the grounds of Porton Down, the site

of Britain’s biological and chemical weapons research establishment. The anthrax was in a form that was

highly unlikely to cause harm.

Mau Mau: The British believe that in late 1952 individuals associated with the Mau Mau African

independence movement were responsible for using a plant toxin to poison livestock in what is now Kenya.

The full extent of these activities is not known.

Polish Resistance: Multiple reports suggest that Polish resistance organizations used biological agents

against German forces during the early part of the World War Two. At least one Polish official claimed that

200 Germans were killed in this fashion, but the claim was never confirmed.

Motives for use

The review of cases identifies a number of reasons that led terrorists and criminals to become

interested in biological agents:

10

Sheryl WuDunn, Judith Miller, and William J. Broad, “How Japan Germ Terror Alerted World,” New York Times, May 26,

1998, pp. A1, A10, provides the most thorough reporting of Aum’s biological warfare activities. See page 47 for additional details.

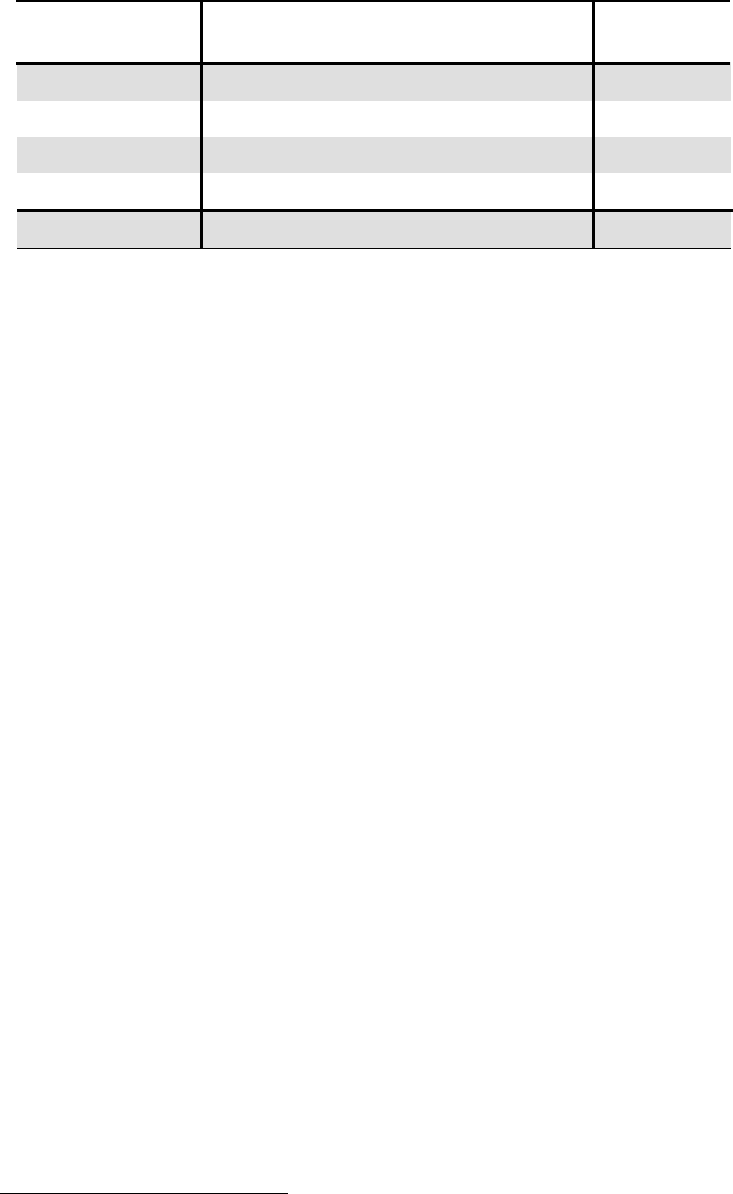

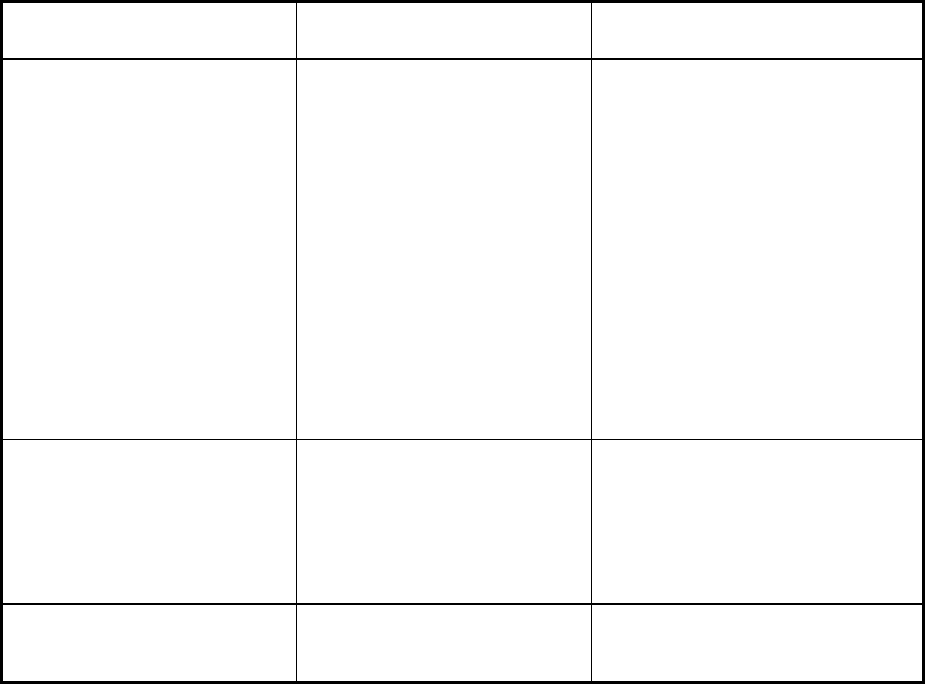

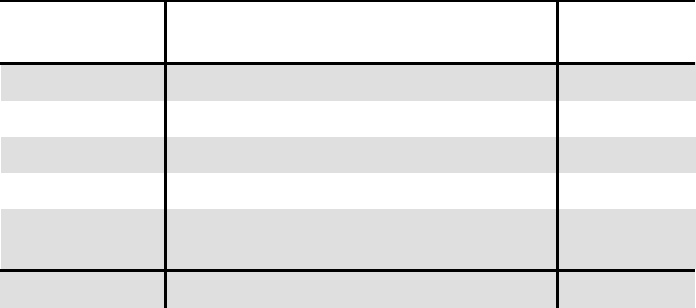

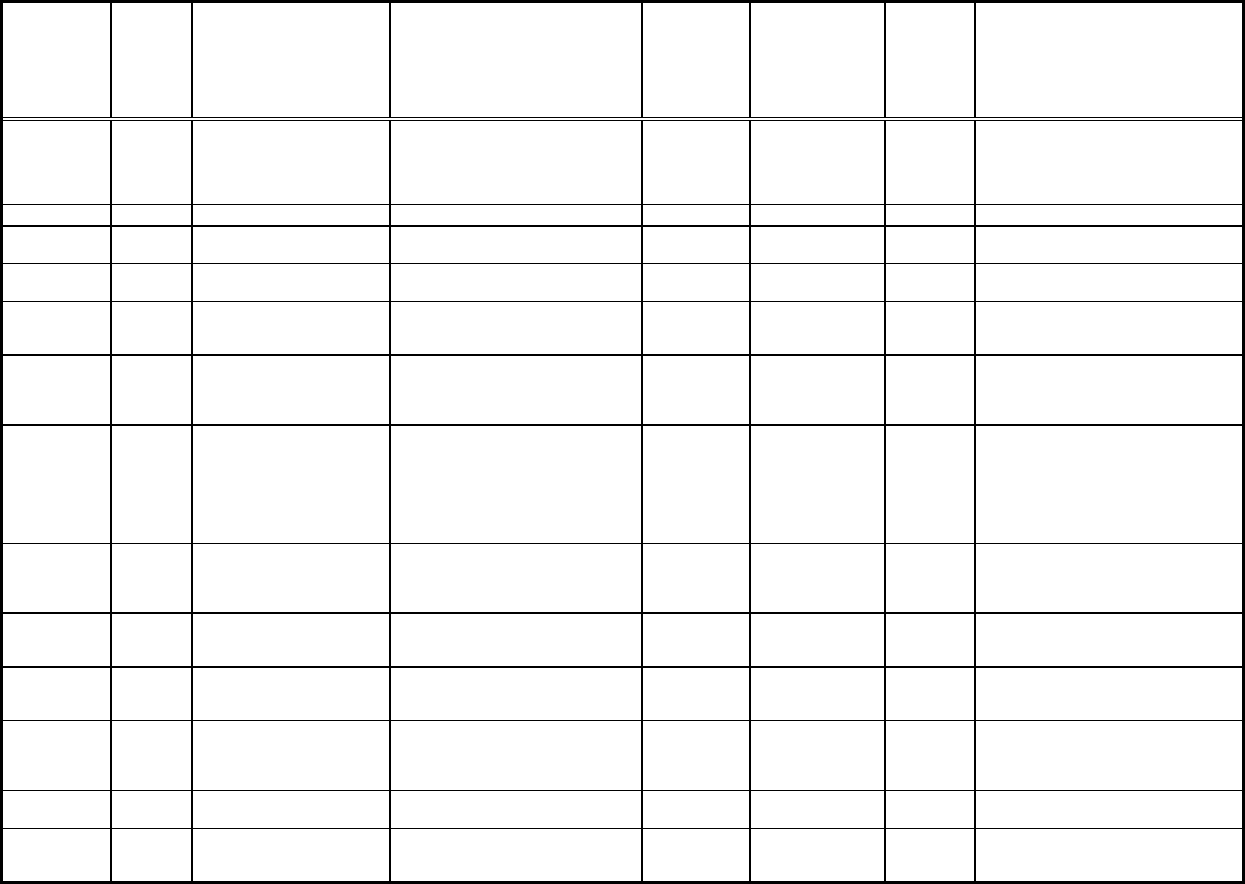

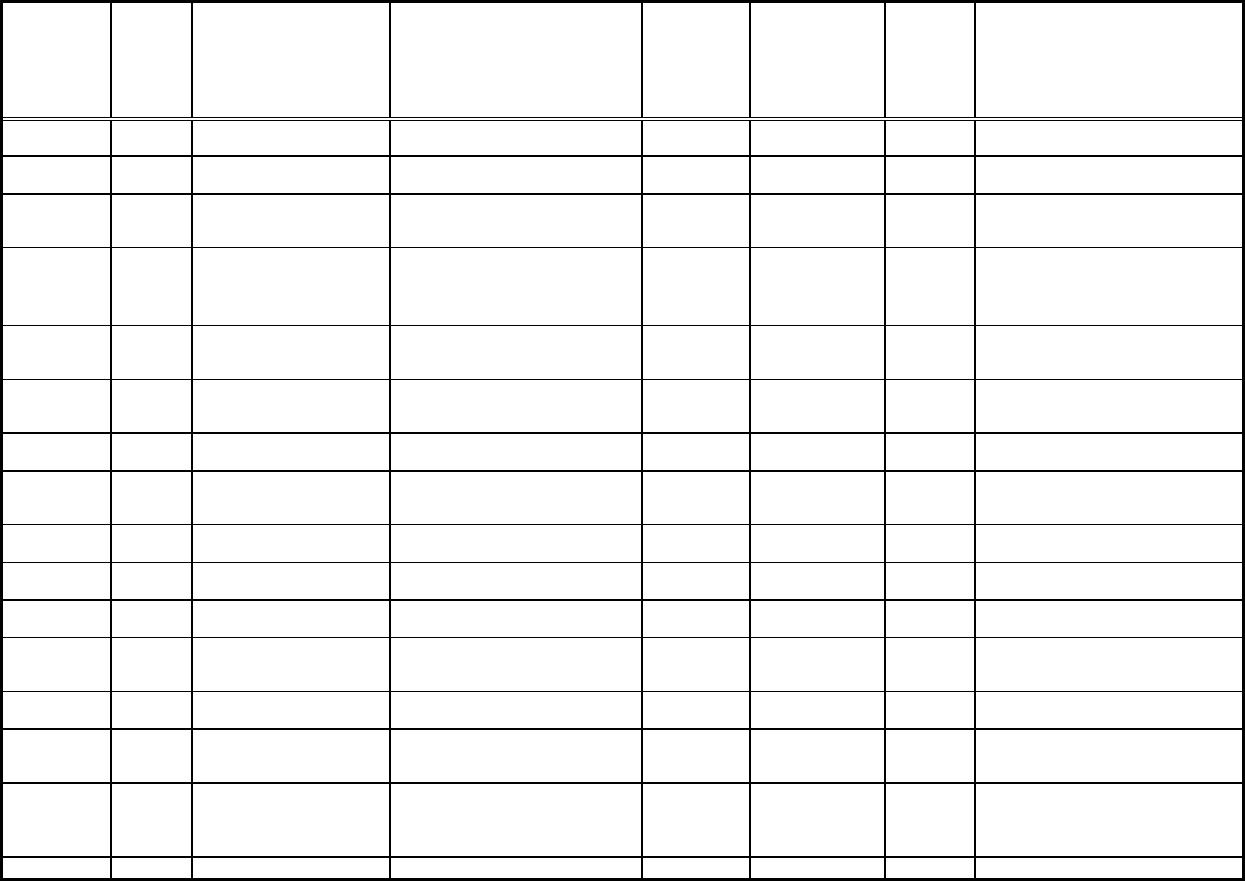

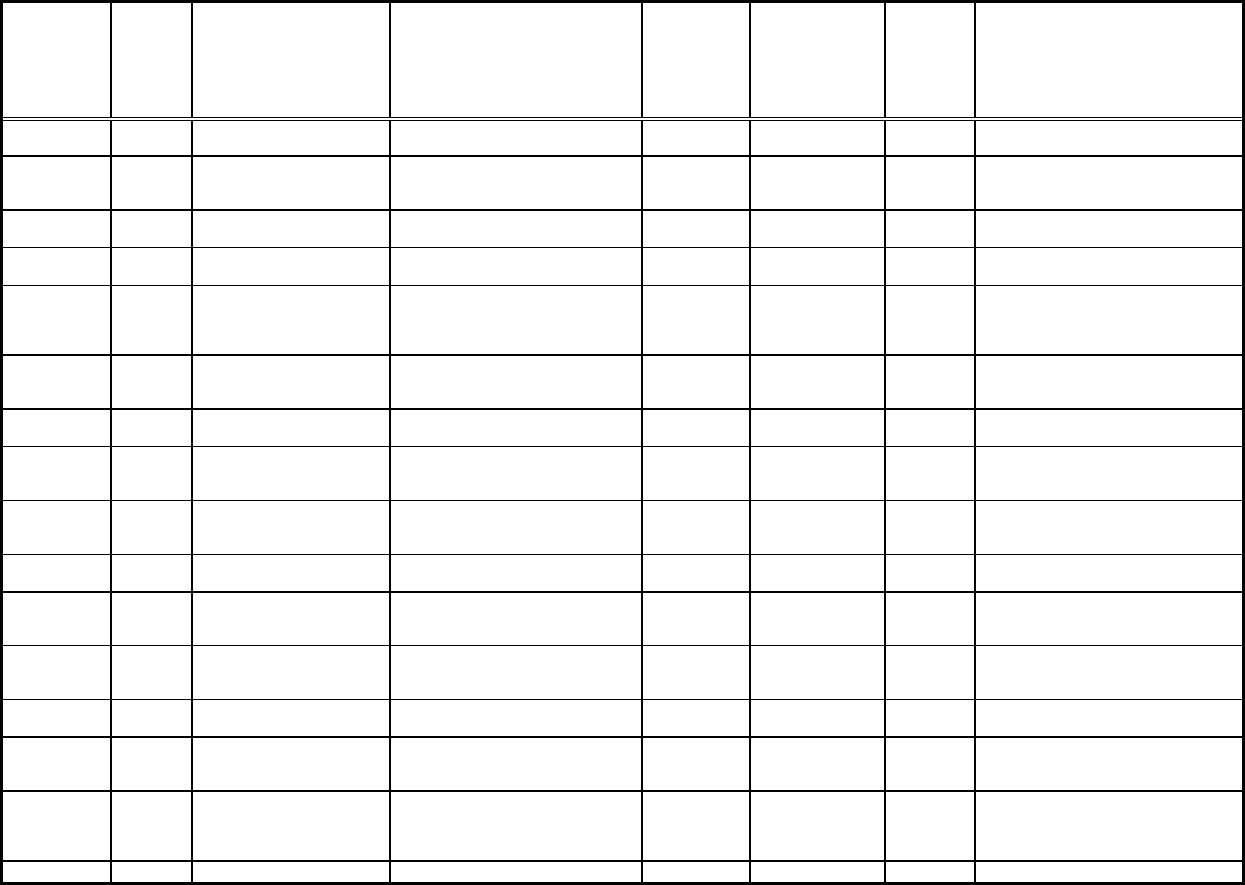

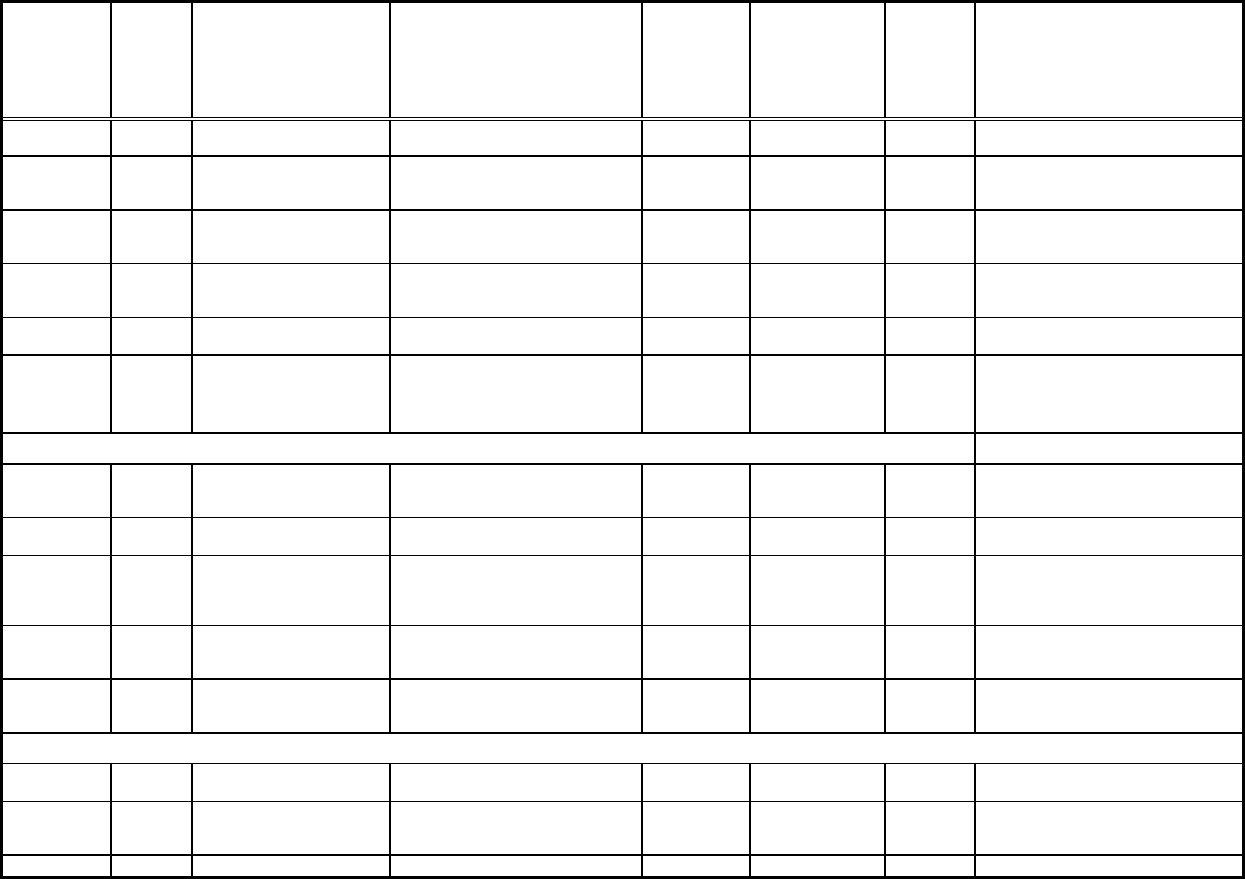

Table 1: Confirmed cases of illicit biological agent activity

Type Terrorist Criminal Other/Uncertain Total

Cases

Acquire and Use 5 16 0 21

Acquire 3 7 2 12

Interest 6 4 0 10

Threat/Hoax 13 29 95 137

Total Cases 27 56 97 180

Source: Based on cases reviewed in Part II. A brief explanation for the decision to include or exclude

each specific case is provided in Appendix A.

9

Mass murder: At least two terrorist groups, motivated by apocalyptic, millenarian visions of creating

a better society, clearly wanted to kill large numbers of people. In principle, such groups also could be

motivated by desires for revenge against a specific political or ethnic group. Steven Pera and Allan Schwander

formed a group, which they called R.I.S.E., with the intention of killing most of the human race so that

mankind could start over again. Aum Shinrikyo also wanted to murder large numbers of people as part of their

efforts to seize control of Japan.

Murder: Several terrorist groups are known to have considered biological agents as weapons to kill

specific individuals. In general, the perceived attractiveness of biological agents results from the belief that the

victim will appear to have died a natural death. The perpetrators hoped that it would prove impossible either to

detect the biological agent (especially if it was a toxin) or to determine that the victim was deliberately infected

(especially if it was a pathogen).

Incapacitation: In at least two instances, the perpetrators wanted to incapacitate large numbers of

people without necessarily killing anyone. According to press accounts, the Weathermen attempted to obtain

biological agents to infect water supplies. They hoped the repressive reaction of the government to such an

incident would radicalize the general population and create additional supporters for their cause. The

Rajneeshees also wanted to incapacitate the citizens of The Dalles, Oregon, so that the people of the

community could not vote in an upcoming election. While the circumstances of that attack are unlikely to

reappear, the case demonstrated that biological agents have utility as mass incapacitants.

Political statement: In one case, the perpetrators used biological agents to make a political statement.

This was the objective of Dark Harvest, a group that apparently was uninterested in causing harm to people or

property, but was willing to “use” of biological agents to send a political message.

Anti-agriculture: This can mean either targeting livestock or crops.

11

As previously mentioned, the

Mau Mau apparently used a plant toxin to kill cattle as part of a concerted campaign that involved known use

of other poisons, including arsenic. Besides this instance, there are no confirmed cases of threats against

11

Lester C. Caudle III, “The Biological Warfare Threat,” pp. 459-461, Frederick R. Sidell, et al., Medical Aspects of Chemical

and Biological Warfare (Washington, D.C.: Office of the Surgeon General, Department of the Army, 1997), provides a summary of the

biological warfare threat to animals and crops.

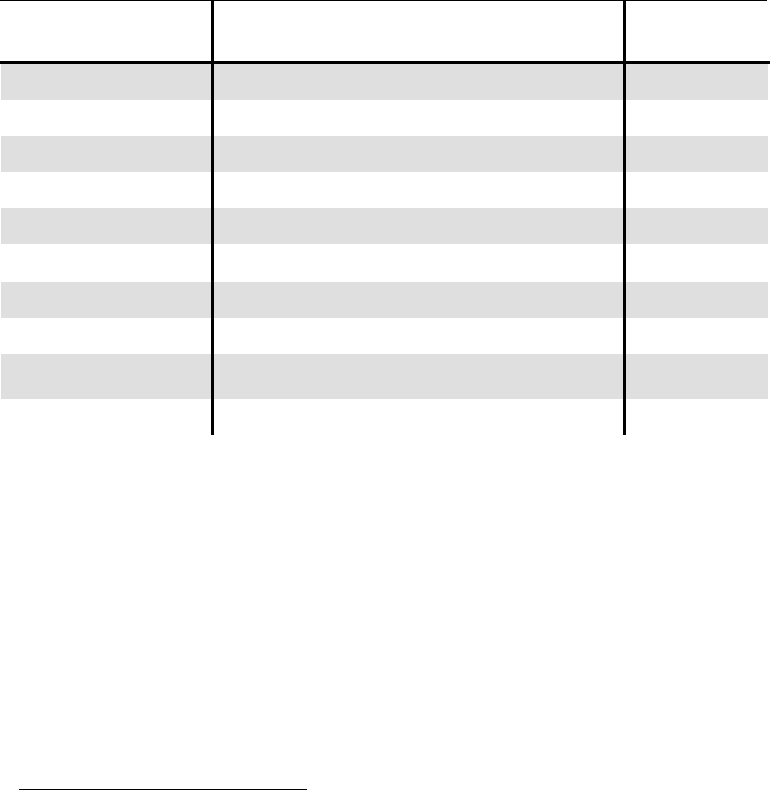

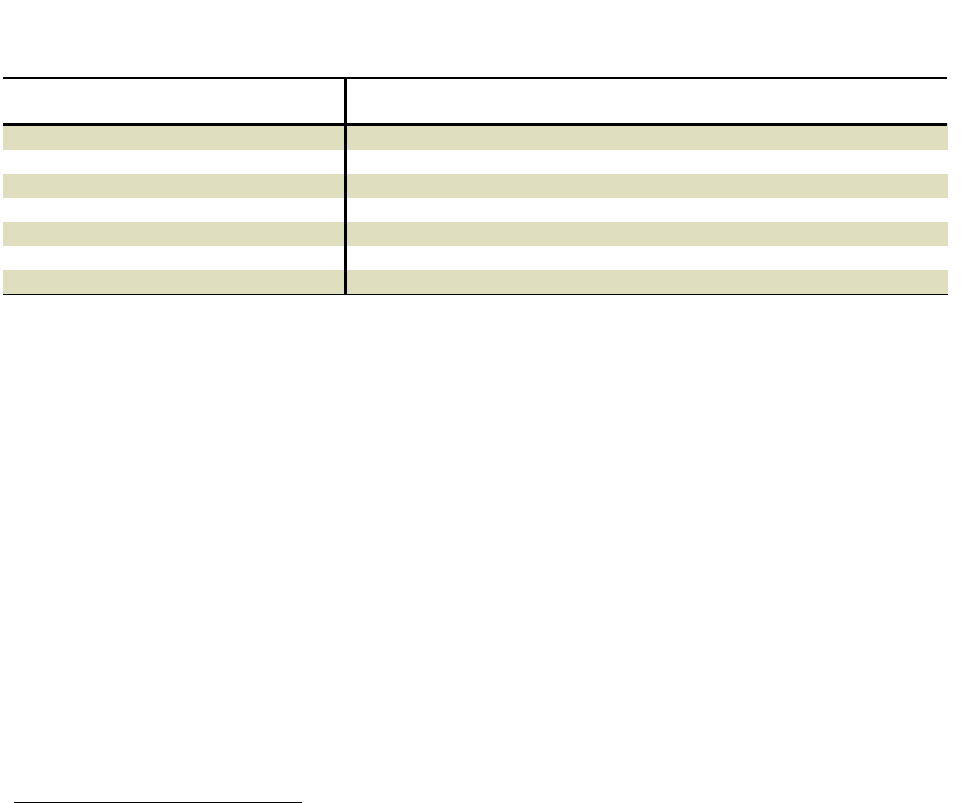

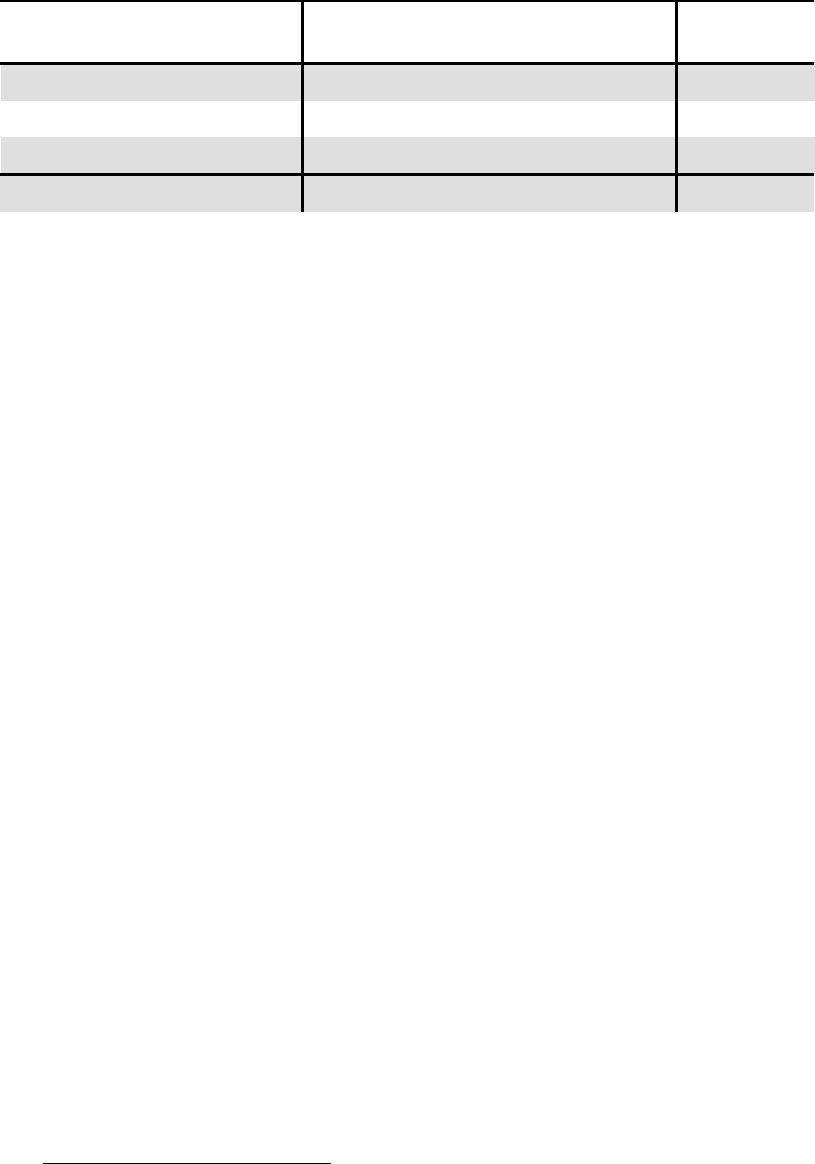

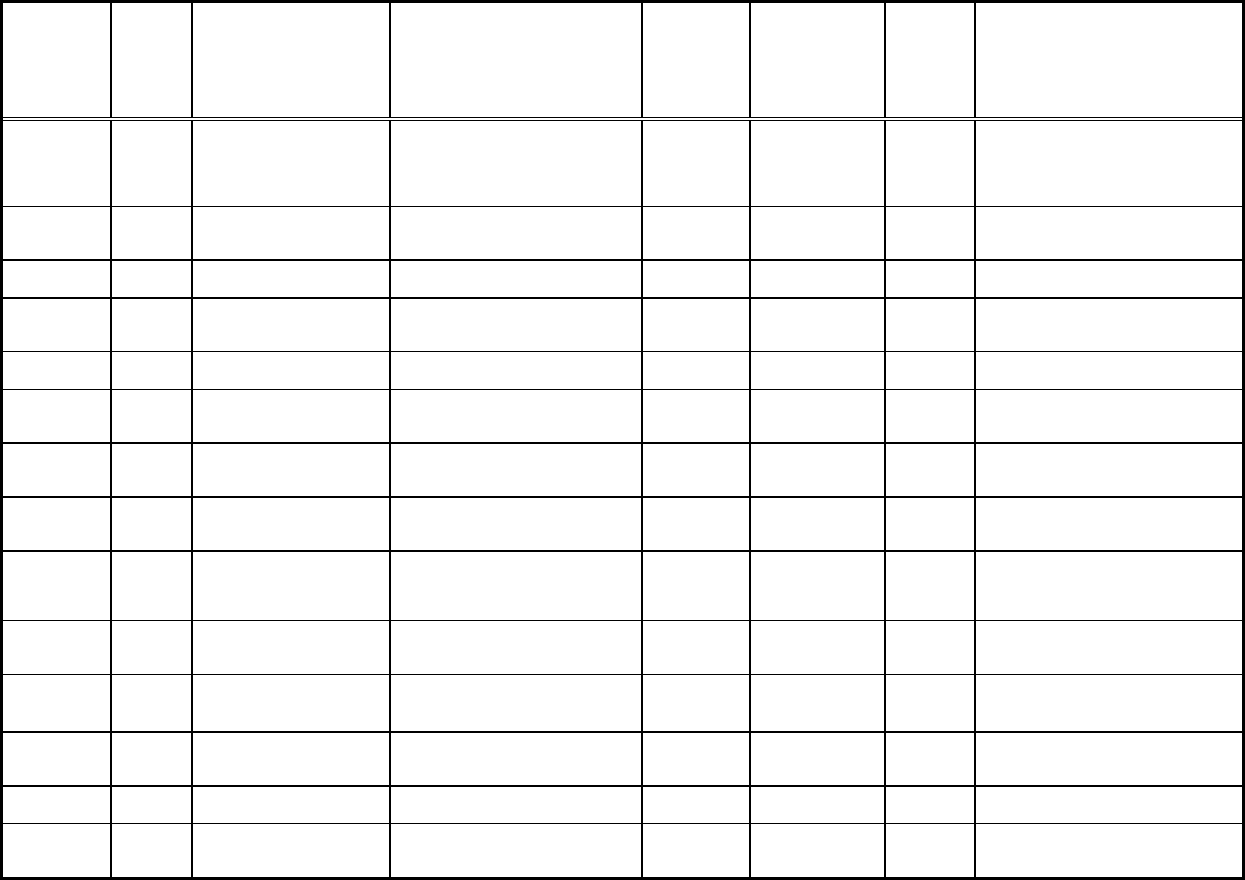

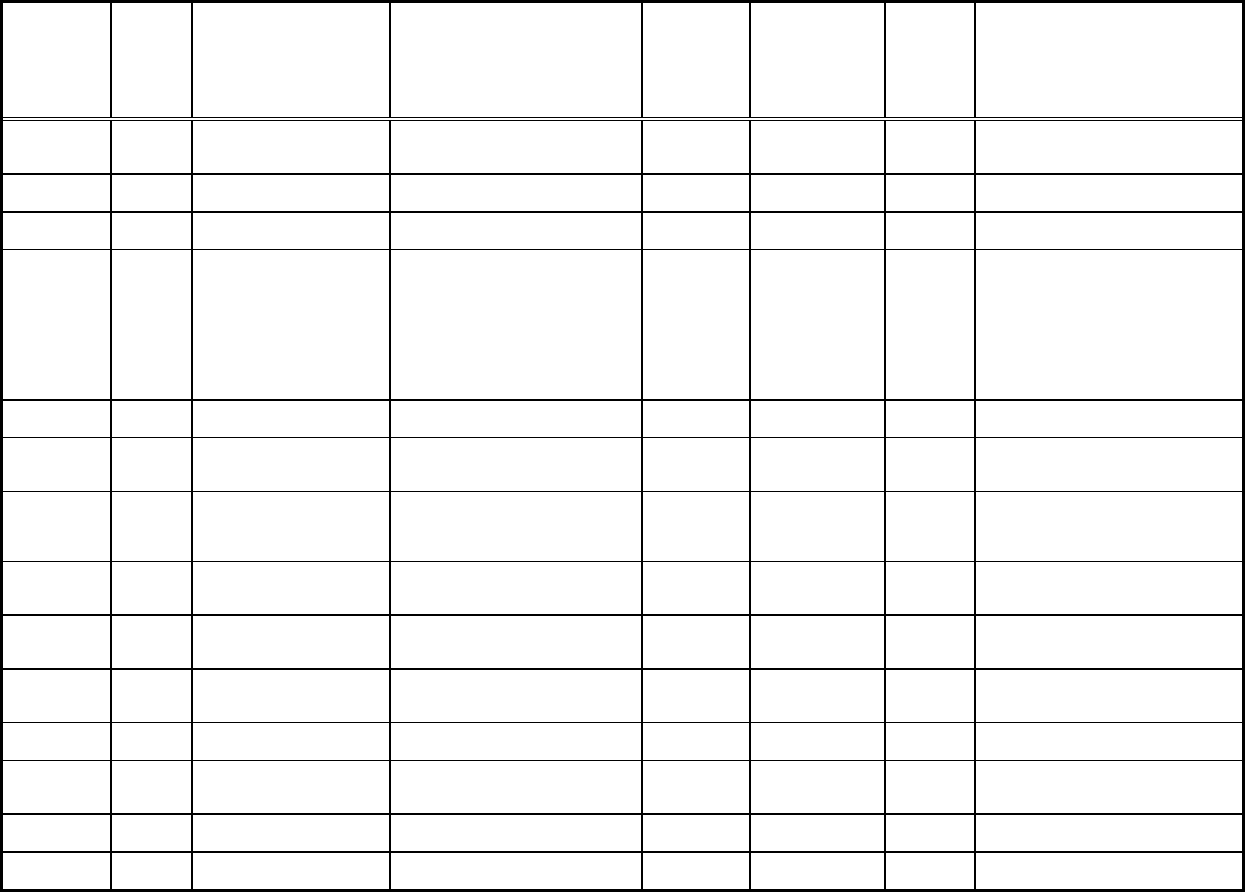

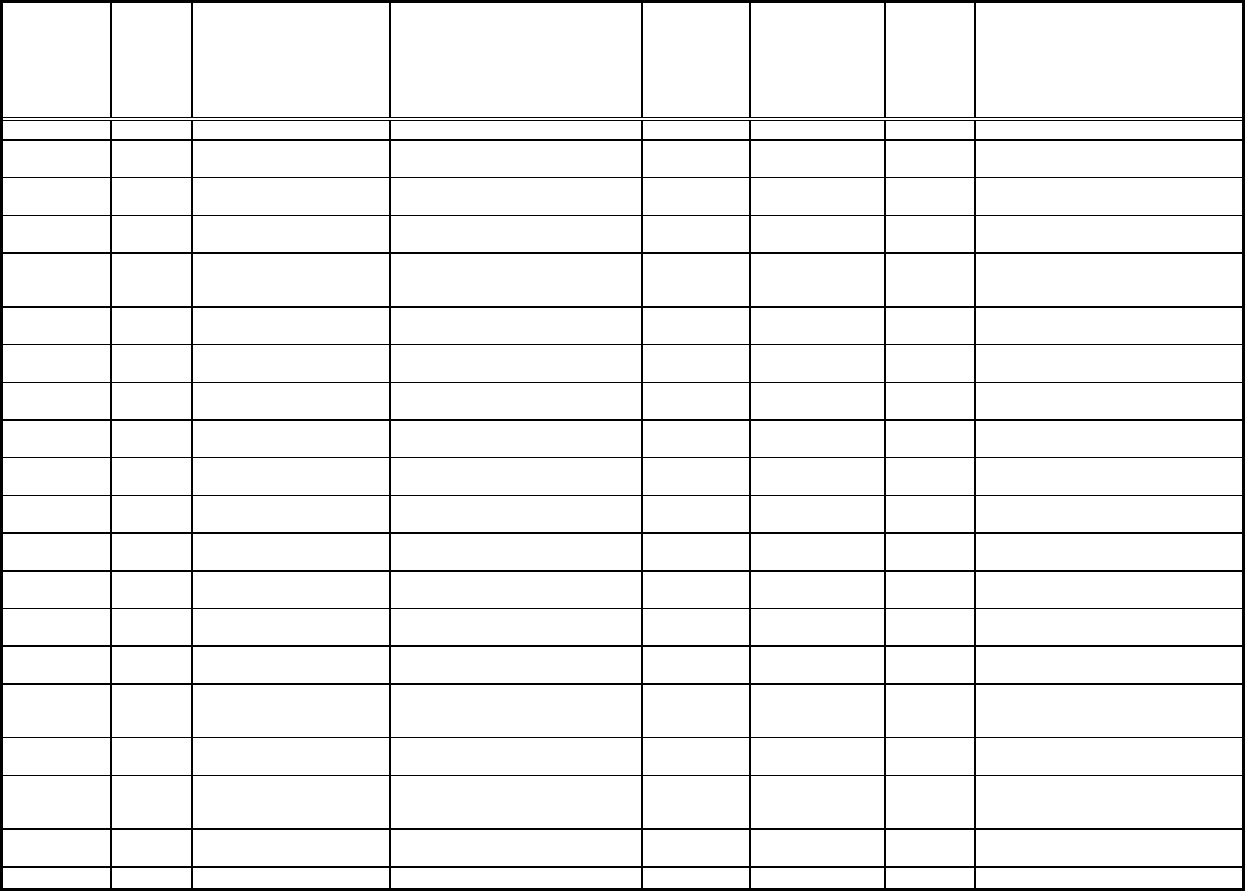

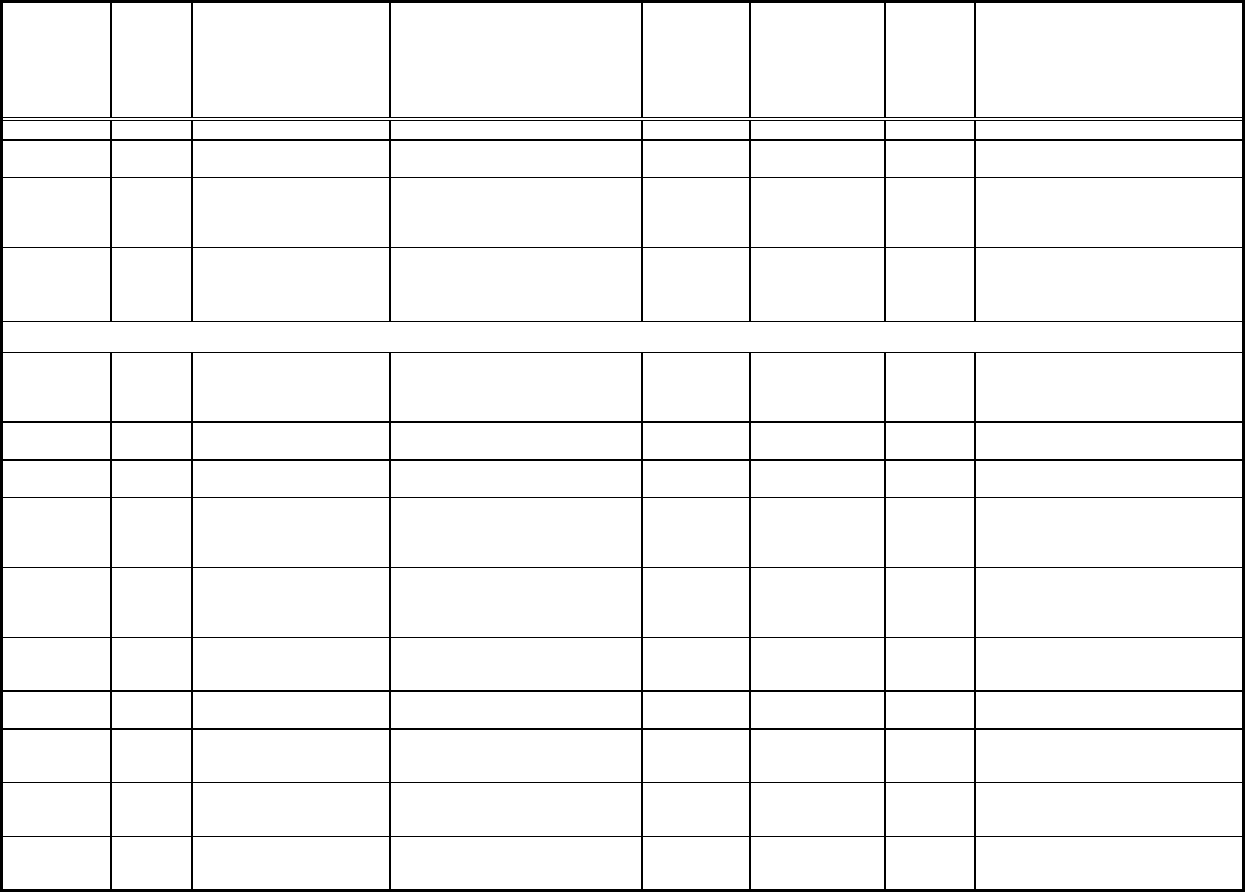

Table 2: Objectives for using biological agents

Type Terrorist Criminal Other/ Uncertain Total

Cases

Murder 4 17 0 21

Terrorize 6 9 22 37

Extortion 0 13 3 16

Disruption 0 5 0 5

Anti-animal/crops 1 2 0 4

Mass Murder 4 0 0 3

Revenge 0 3 0 3

Incapacitation 2 0 0 2

Political statement 1 0 0 1

Unknown 9 7 72 88

Note: Because some perpetrators had multiple objectives, the totals in this table may

exceed the total number of cases.

10

agriculture.

12

Numerous biological agents can be used to target crops and livestock. The viability of the threat

is demonstrated by the efforts by several countries to develop biological agents for use against crops. The

United States Army weaponized several agents for use against crops prior to the 1969 decision to dismantle the

U.S. offensive BW program.

13

The Soviet Union had a substantial program to agents for use against crops and

animals.

14

Iraq admits that during the 1980s it was developing at least one biological agent for use against

crops, wheat cover smut, which kills the affected plants.

15

Criminal motives: An examination of criminal use of biological agents reveals additional motives.

Many of the criminal uses of biological agents involved extortion. Extortion was the motive in about 9 per cent

of the confirmed cases. Generally, the target was a food or grocery company. In only one of these cases is the

perpetrator known to have had the capability to undertake the threatened contamination. There is no

documented case of a terrorist group using biological agents to extort money. However, several unidentified

individuals tied political agendas to extortion plots involving threats of biological weapons use. Many of the

cases appear to involve deliberate efforts to terrorize the victims. In most of these cases, the perpetrator

appeared to want to accomplish nothing more than to make the victims worry about their health. At least one

case, involving the Japanese physician Dr. Mitsuru Suzuki, appears to have been motivated by the desire for

revenge. Suzuki was angry about the treatment he was receiving as a resident in his medical training, and

allegedly retaliated by infecting other health care providers and patients. Suzuki’s motivations are complicated

by suggestions that he may have been creating clinical cases to further his academic research into S. typhi.

Trends in Bioterrorism

The available evidence indicates that there is an explosion of interest by criminals in biological

agents. Forty of the 56 confirmed criminal cases occurred in the 1990s. Similarly, 19 of 27 confirmed terrorist

cases occurred in the 1990s. This suggests growing interest in biological agents.

16

The most extensive official

comment on terrorist and criminal interest in biological weapons comes from 1997 testimony given by Director

Louis Freeh. At that time, he made the following observations:

The FBI has also investigated and responded to a number of threats which involved biological

agents and are attributed to various types of groups or individuals. For example, there have been

apocalyptic-type threats which actually advocate destruction of the world through the use of WMD

[weapons of mass destruction]. We have also been made aware of interest in biological agents by

individuals espousing white-supremacist beliefs to achieve social change; individuals engaging in

criminal activity, frequently arising from jealousy or interpersonal conflict; individuals and small

anti-tax groups, and some cult interest. In most cases, threats have been limited in scope and have

targeted individuals rather than groups, facilities, or critical infrastructure. Threats have surfaced

which advocate dissemination of a chemical agent through air ventilation systems. Most have made

little mention of the type of device or delivery system to be employed, and for this reason have

been deemed technically not feasible. Some threats have been validated.

17

According to 1997 testimony by DCI George Tenet, the intelligence community also has found evidence that

foreign terrorist groups are showing greater interest in biological weapons. “We are increasingly seeing

terrorist groups looking into the feasibility and effectiveness of chemical, biological, and radiological

weapons.”

18

Overall, the CIA concluded, “The current WMD terrorist threat is considered low but

12

There are documented instances of chemical contamination of food to prevent sale of agricultural produce. For example,

mercury was injected into oranges exported from Israel in 1978, causing a dramatic reduction in demand for its citrus crop. See Purver,

Chemical and Biological Terrorism, pp. 87-88, for a review of the literature discussing this event.

13

Specifically, the United States weaponized and stockpiled rice blast, rye stem rust and wheat stem rust. See Table 1 in George

W. Christopher, et al., “Biological Warfare: A Historical Perspective,” JAMA, Vol. 278, No. 5 (August 6, 1997), p. 412. The rice blast was

aimed at China, while the other two were targeted at the Soviet Union. For one view on the utility of such attacks, see J.H. Rothschild,

Tomorrow’s Weapons (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964), pp. 121-131.

14

Judith Miller, “U.S. to Use Lab for More Study Of Bioterrorism,” New York Times, September 22, 1999, p. A25.

15

R. A. Zilinskas, “Iraq’s Biological Weapons: The Past as Future?,” JAMA, Vol. 278, No. 5 (August 6, 1997), p. 419.

16

This conclusion differs significantly from the author’s original views, when it appeared that only three of 12 terrorist cases

took place in the 1990s. New cases and additional research on old cases have resulted in an increase in the number of identified terrorist

cases from three to eight.

17

Statement of Louis J. Freeh, Director, Federal Bureau of Investigation, before the United States Senate Appropriations

Committee Hearing on Counterterrorism, May 13, 1997.

18

United States Senate, Select Committee on Intelligence, Current and Projected National Security Threats to the United States

(Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1997), p. 8.

11

increasing.”

19

In April 1998, Clinton Administration officials reportedly testified during a classified hearing

before the Senate Intelligence Committee that there was a “high degree of likelihood that such an attack would

occur in 10 years.”

20

There is also reason for concern that future bioterrorism attacks may be more deadly than past

incidents. Three factors account for the change. First, an increasing number of terrorist groups—foreign and

domestic—are adopting the tactic of inflicting mass casualties to achieve ideological, revenge, or “religious”

goals, often hard to understand. If such groups acquired an effective aerosol dissemination capability for

anthrax, for example, they could potentially kill tens or hundreds of thousands of people. The World Trade

Center and Oklahoma City bombings both were conducted by people who had no compunction about mass

killing and, in fact, sought to kill large numbers of civilians.

21

Second, the technological sophistication of the

terrorist groups is growing. We now know that some terrorists have tried to master the intricacies of aerosol

dissemination of biological agents. Perhaps more disturbing for the future, some terrorists might gain access to

the expertise generated by a state-directed biological warfare program. Finally, Aum Shinrikyo demonstrated

that terrorist groups now exist with resources comparable to some governments. Therefore, it is seems

increasingly likely that some group will become capable of using biological agents to cause massive casualties.

19

United States Senate, Select Committee on Intelligence, Current and Projected National Security Threats to the United

States, p. 94.

20

As characterized by Senator Carl Levin, reported by “Reno, FBI Head Warn Of Terrorism,” Associated Press, April 23,

1998, 4:44 A.M. feed. The FBI has issued some statistics that appear to indicate a trend towards greater use of nuclear, biological, and

chemical weapons. In testimony before the same committee, Louis Freeh reported that the Bureau investigated 114 cases involving

chemical, biological, or other weapons of mass destruction during the last year. See Tim Weiner, “U.S. May Stockpile Medicine for

Terrorist Attack,” New York Times, April 23, 1998.

The significance of that figure is difficult to interpret. The Department of Defense defines a weapon of mass destruction to

include nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons, but the legal definition is different. “The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement

Act of 1994,” defines a WMD to include “any destructive device as defined in section 921” of Title 18 of the U.S. Code. According to

section 921, a destructive device is “any gun with a barrel larger than half an inch, any bomb, any grenade, any “rocket having a propellant

charge of more than four ounces.” In other words, to the FBI, a weapon of mass destruction is basically any destructive device, including a

great many that clearly cannot cause mass destruction and that have nothing to do with nuclear, biological, or chemical weapons.

Nevertheless, the Director’s statement apparently refers only to nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons cases.

21

Bruce Hoffman, Inside Terrorism (London: Victor Gollancz, 1998), pp. 92-94.

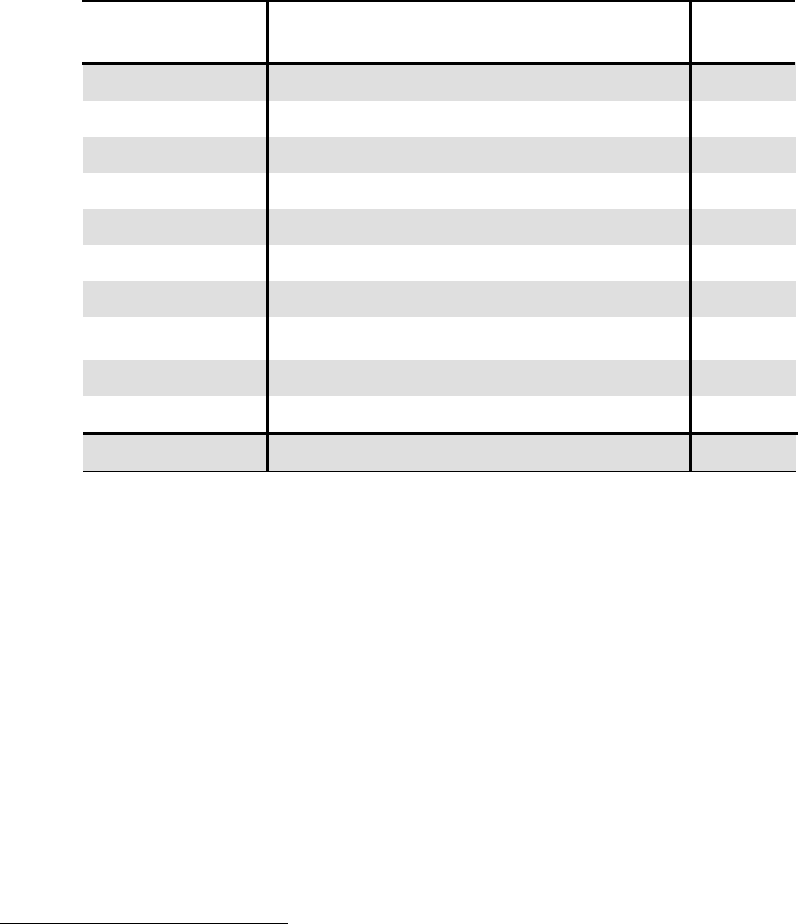

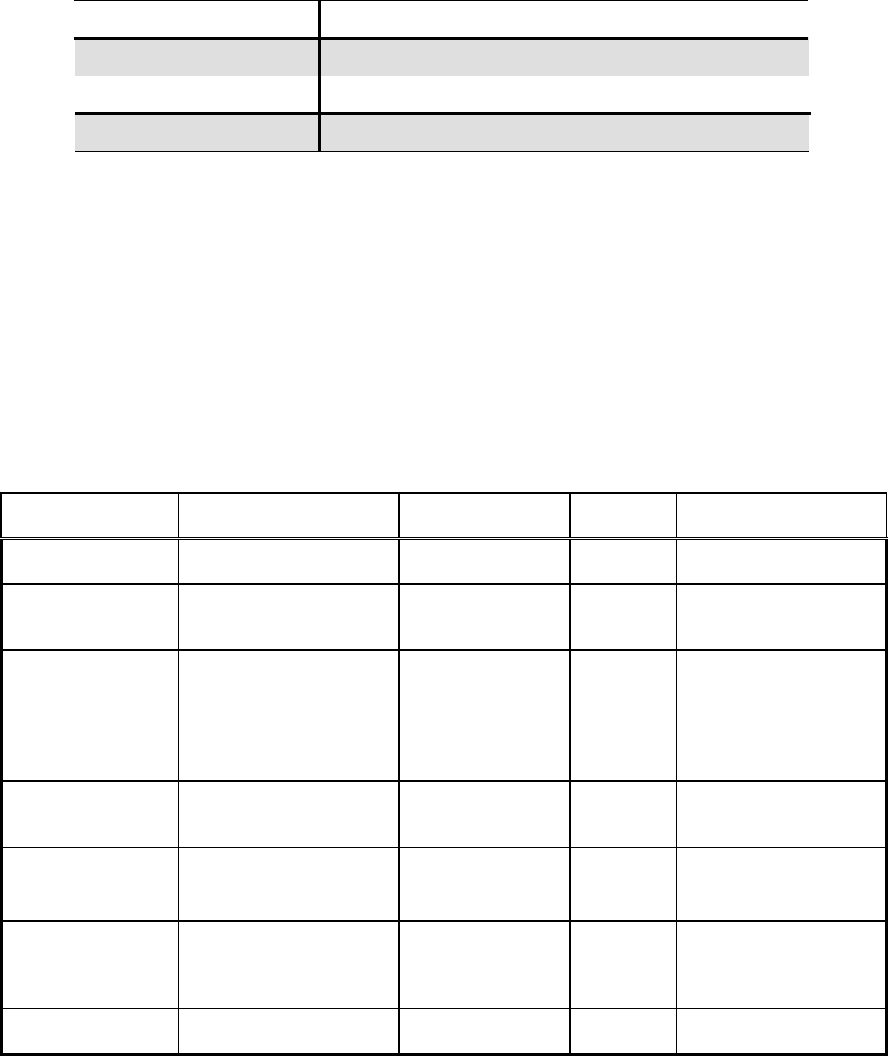

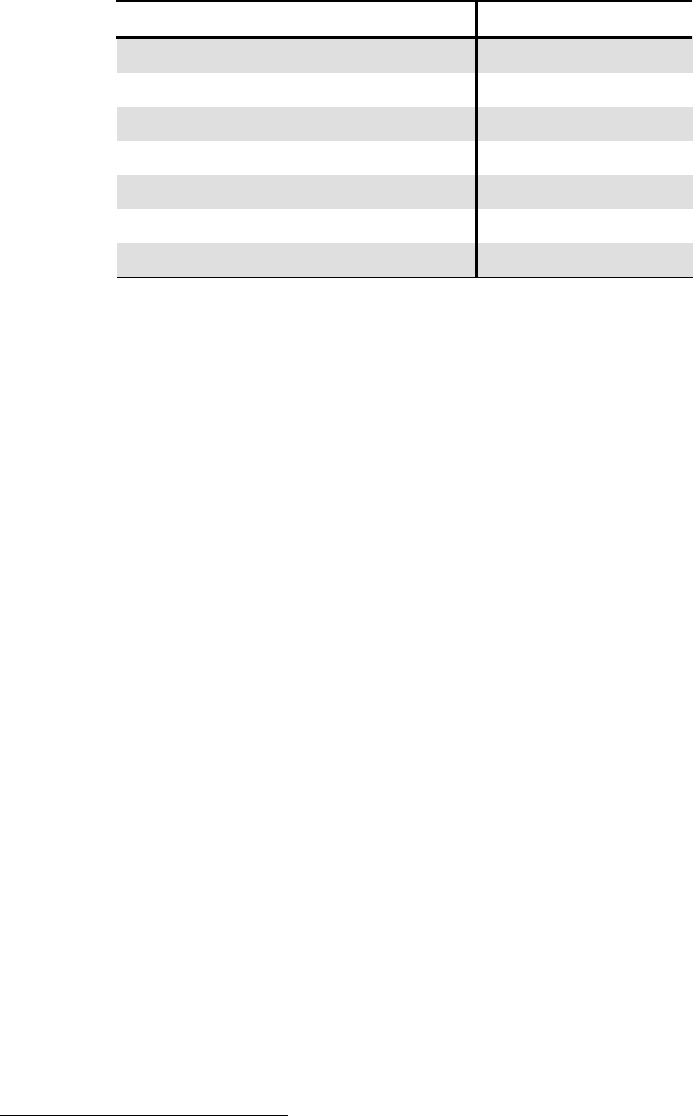

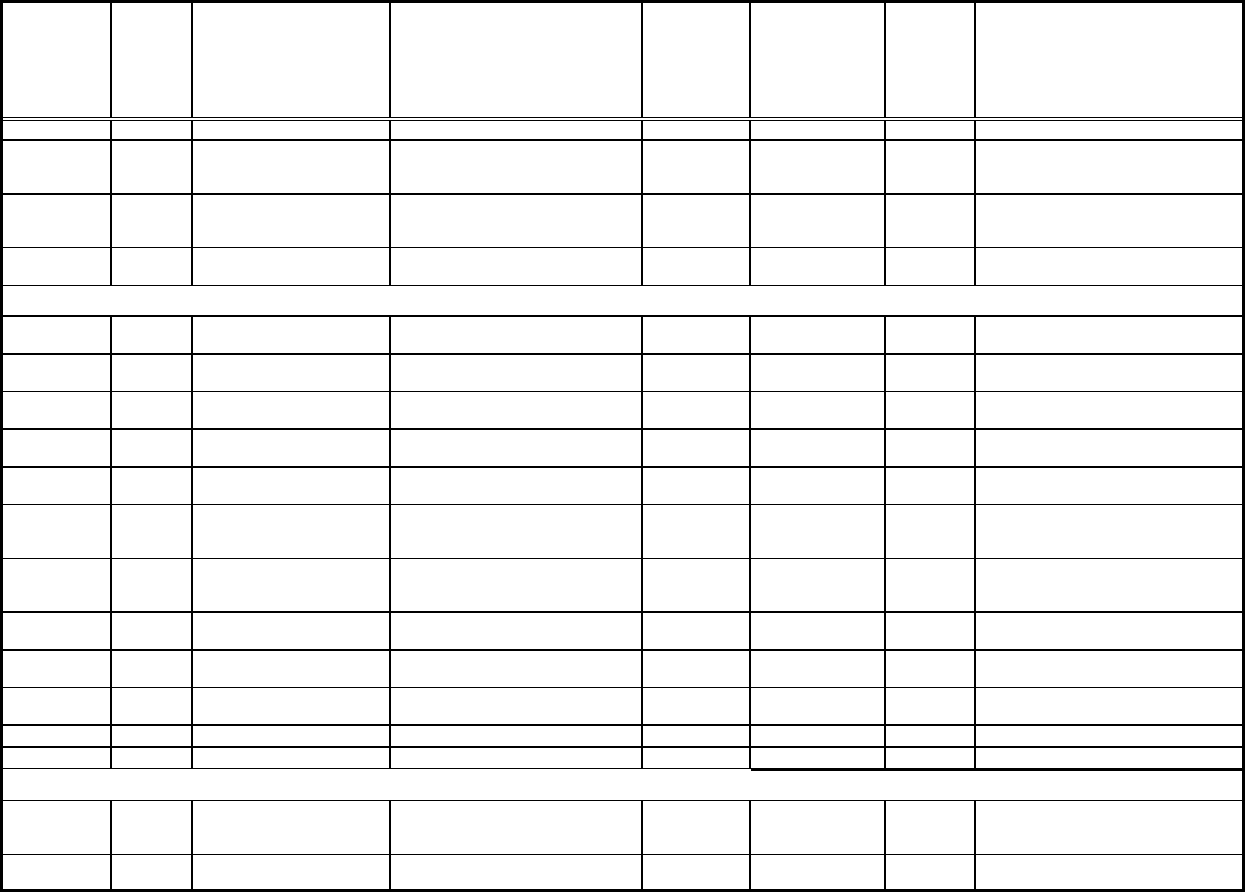

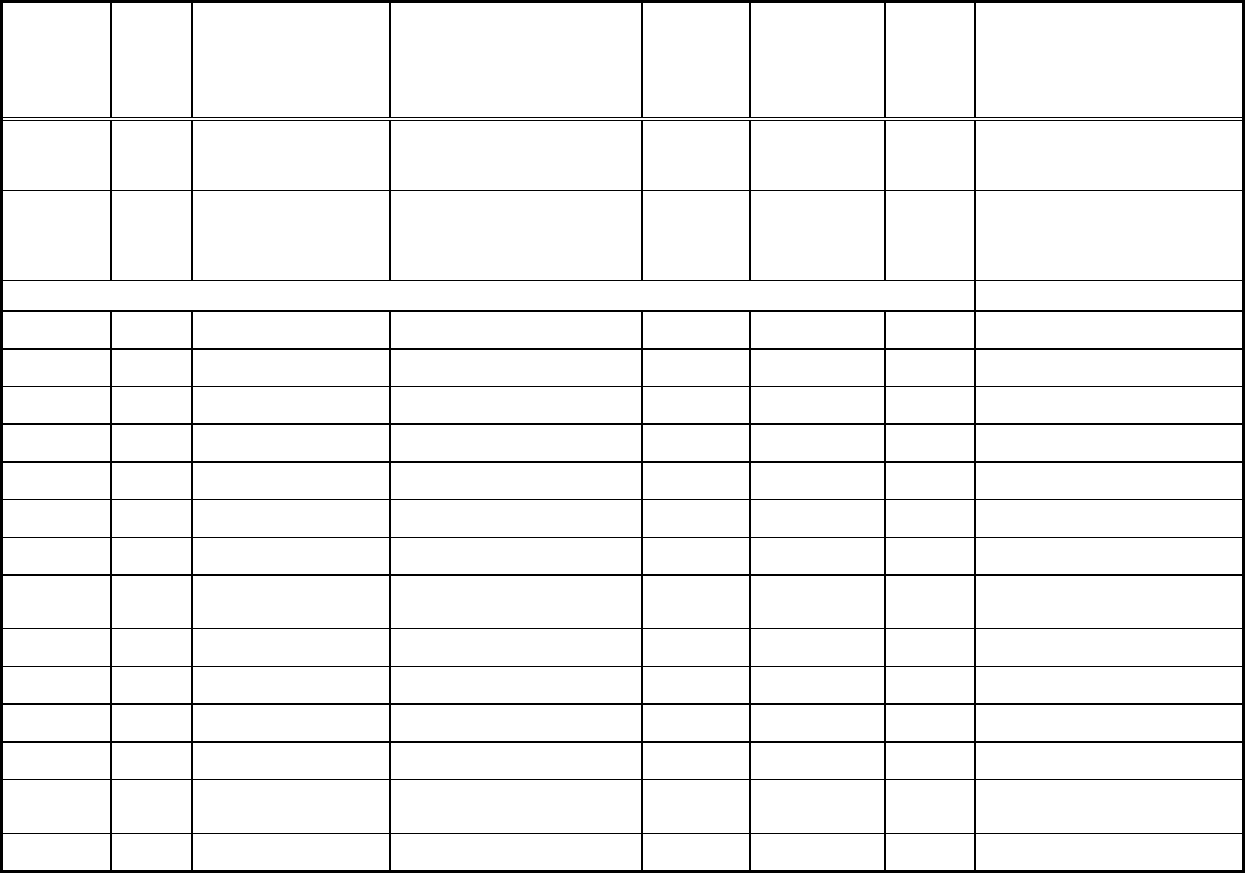

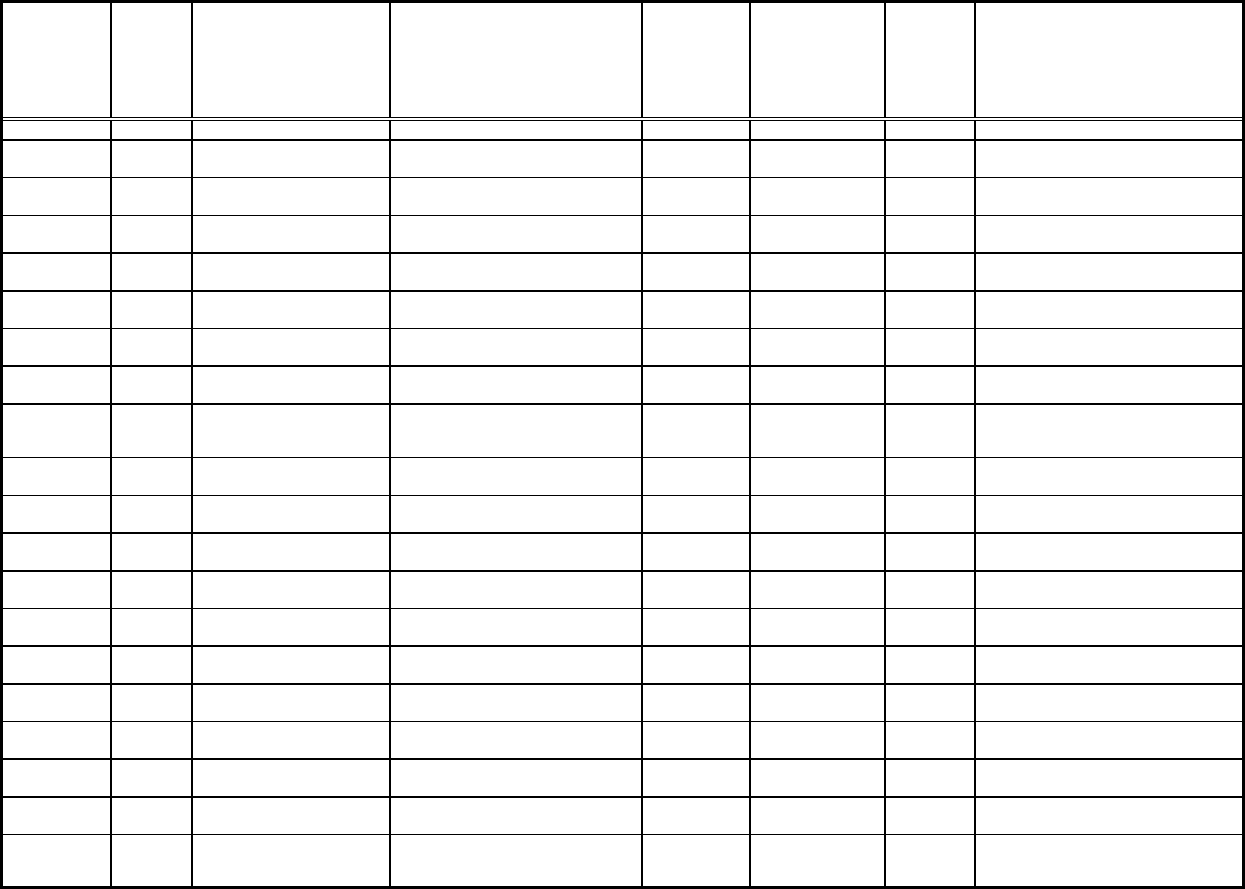

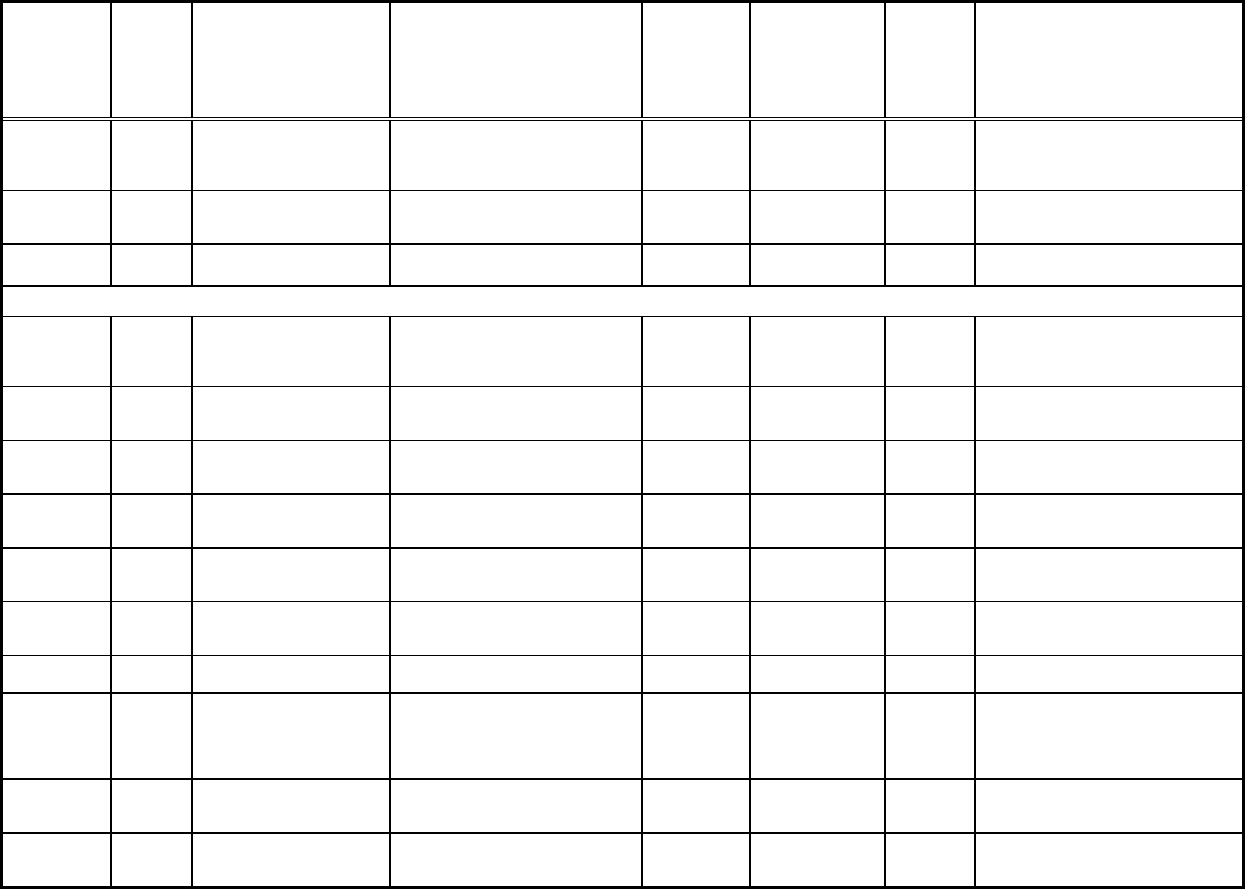

Table 3: Trends in bioagent cases

Terrorist Criminal Other/

Uncertain

Total

1990-1999 19 40 94 153

1980-1989 3 6 0 9

1970-1979 3 2 3 8

1960-1969 0 1 0 1

1950-1959 1 0 0 1

1940-1949 1 0 0 1

1930-1939 0 3 0 3

1920-1929 0 0 0 0

1910-1919 0 3 0 3

1900-1909 0 1 0 1

Totals 27 56 97 180

12

Acquiring Biological Agents

Biological agents are organisms or toxins produced by organisms that can be used against people,

animals, or crops. In contrast, chemical agents, poisonous substances that can kill or incapacitate, are man-

made materials.

22

Pathogens: Pathogens are naturally occurring microorganisms that cause disease. There are hundreds

of pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. Among the pathogens often mentioned as

potential biological agents are Bacillus anthracis, the organism that causes anthrax, and Yersinia pestis, the

organism that causes plague.

23

Because pathogens are living organisms, they are self-replicating. Exposure to

even a small number of organisms can produce severe symptoms or even death. Thus, it is believed that the

ID

50

for pneumonic plague is fewer than 100 Y. pestis organisms, while 8-10,000 B. anthracis spores will cause

inhalation anthrax.

24

Only some pathogens are transmissible from person to person. For example, someone suffering from

pneumonic plague can transmit Y. pestis organisms to others, creating a serious risk of epidemic spread. In

contrast, bubonic plague is communicable generally only if someone is exposed to pus from an infected

22

There is no standard definition of a biological agent. The definition used here follows the definition in Frederick R. Sidell and

David R. Franz, “Overview: Defense Against the Effects of Chemical and Biological Warfare Agents,” pp. 4-5, in Frederick R. Sidell, et

al., Medical Aspects of Chemical and Biological Warfare (Washington, D.C.: Office of the Surgeon General, Department of the Army,

1997): “Biological agents are either replicating agents (bacteria or viruses) or nonreplicating materials (toxins or physiologically active

proteins or peptides) that can be produced by living organisms. Some of the nonreplicating biological agents can also be produced through

either chemical synthesis, solid-phase protein synthesis, or recombinant expression methods.”

The Department of Defense officially defines a biological agent as “a microorganism that causes disease in personnel, plants, or

animals or causes the deterioration of materiel.” It separately defines a toxin agent as “a poison formed as a specific secretion product in

the metabolism of a vegetable or animal organism as distinguished from inorganic poisons. Such poisons can also be manufactured by

synthetic processes.” See Joint Publication 1-02, DOD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, as found at

http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/jel/doddict/. A slightly different definition of toxins was offered in Medical Management of Biological

Casualties (Fort Detrick, Frederick, Maryland: U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, March 1996), p. 75: “Toxins

are defined as any toxic substance of natural origin produced by an animal, plant, or microbe. They are different from chemical agents such

as VX, cyanide, or mustard in that they are not man-made.”

The Biological Weapons Convention provides no specific definition. Article I requires adherents not to “develop, produce,

stockpile or otherwise acquire or retain: Microbial or other biological agents, or toxins whatever their origin or method of production, of

types and in quantities that have no justification for prophylactic, protective or other peaceful purposes.” Thus, the convention really

provides little guidance as to what is prohibited.

23

There is considerable misunderstanding of biological agents. In February 1998, federal officials alleged that some

perpetrators had “military grade anthrax”, a meaningless statement. There are many different strains of B. anthracis, but there is no

uniquely “military” type. Rather, biological agents used in biological weapons have been strains of naturally occurring organisms.

Similarly, there is considerable confusion about plague. Y. pestis, the plague bacillus, causes several different diseases, including bubonic

plague and pneumonic plague, but there is no bubonic plague or pneumonic plague organism.

24

The ID

50

is the dose (D) at which 50 per cent of those exposed will become infected (I). The LD

50

is the dose (D) that is lethal

(L) to 50 per cent of those exposed. With some diseases, the ID

50

might be identical to the LD

50

. The figures are from Medical

Management of Biological Casualties, Appendix.

According to one estimate, there are 10

10

B. anthracis spores (or 10 billion) in a milligram, which is one-thousandths of a gram

or one-millionth of a kilogram. Thus, a milligram contains roughly one million infective doses. Because the agent cannot be disseminated

perfectly, it could not infect anywhere near that number of people. According to one estimate, the accidental release of B. anthracis spores

from the Soviet biological weapons facility at Sverdlovsk killed at least 66 people and involved somewhere between a few milligrams and

a gram of agent. It appears that 1-3 per cent of those in the area covered by the B. anthracis cloud died. Thus, if only 6 milligrams were

disseminated, the agent cloud would have contained at least 6 million lethal doses, which is nearly 100,000 times the number of people

who actually died. See Matthew Meselson, Jeanne Guillemin, Martin Hugh-Jones, Alexander Langmuir, Ilona Popova, Alexis Shelokov,

and Olga Yampolskaya, “The Sverdlovsk Anthrax Outbreak of 1979,” Science, Volume 266, Number 5188 (November 18, 1995), pp.

1202-1208. See also, Matthew Meselson, “Note Regarding Source Strength,” November 21, 1994.

Estimates of LD

50

should be treated cautiously. Generally, they are based on extrapolation of animal data. A recent review of

the published anthrax research reached the following conclusion on the susceptibility of humans to infection from anthrax.

The data available on human exposure to B. anthracis spores do not allow us to establish the minimum critical

dose required to establish any of the forms of the disease. From the information available, it can be said that

man appears to be moderately resistant to anthrax. It is crucial to note that any critical dose will depend very

heavily on the strain of B. anthracis, particularly the presence of the virulence factors, and on the health of the

individual host.

See A. Watson and D. Keir, “Information on which to base assessments of risk from environments contaminated with anthrax spores,”

Epidemiology and Infection, 113(1994), pp. 479-490.

13

person. Anthrax is not contagious, and only those exposed to the released B. anthracis spores are likely to

become infected.

25

Pathogens require an incubation period before symptoms of infection appear. For some diseases, the

incubation period is only a few days, while for others it might be several weeks. Typically, 3-5 days pass

before the acute symptoms of inhalation anthrax appear, while for Q fever (caused by the Coxiella burnetii

organism) the incubation period is two to three weeks, depending on the size of the dose.

26

Toxins: Toxins are poisonous chemicals produced by living organisms. Among the best known are

botulinum toxin, which is produced by the bacteria Clostridium botulinum, and ricin, which is extracted from

the seed of the castor bean plant. Unlike pathogens, toxins are not self-replicating, so their physical effects are

solely a result of the agent released.

While toxins share many characteristics with chemical agents, they also have some significant

differences.

27

Many toxins are more toxic than the most lethal of chemical agents. Thus, the LD

50

for botulinum

toxin when injected is 0.001 micrograms per kilogram of body weight. In contrast, VX, perhaps the most lethal

of the chemical agents, has an LD

50

of 15 micrograms per kilogram of bodyweight.

28

Toxins are not volatile,

unlike many chemical agents, and thus do not naturally generate a persistent threat. Generally, toxins are not

dermally active, meaning that contact with the skin is insufficient to produce disease. Rather, the agent must be

brought into the body, either by ingestion, inhalation, or through an opening in the skin.

29

The quantity of toxin required to achieve a desired effect is dependent on the lethality of the agent.

According to one estimate, eight tons of ricin would be needed to blanket an area to achieve the same effect

accomplished using only eight kilograms of botulinum toxin. For many toxins, the quantities of agent required

to produce a given effect are similar in size to that for the more lethal chemical agents.

30

Sources of agent

Only 33 of non-state cases involved actual acquisition of agent. Four different methods were used:

purchase from legitimate suppliers, theft, self-production, and use of material of natural origin contaminated

with biological agents. The data on acquisition routes are summarized in Table 4.

Gaining access to biological agents never appears to have been a significant limiting factor. In fact,

acquiring biological agents has usually proven to be relatively easy. In a few cases, pathogens were acquired

from culture collections, usually legitimately but sometimes not, while the perpetrators usually produced

toxins. Culture collections were a preferred source for pathogens even when the terrorists or criminals

possessed the skills to culture organisms acquired in nature. Reliance on such collections may be a result of the

relative ease with which the cultures can be obtained. Alternatively, perpetrators may prefer to obtain cultures

from standardized sources to ensure purity and avoid cross-contamination of cultures with unwanted

organisms. In addition, the effectiveness of biological agents depends heavily on the specific strain of the

organism, and it may be difficult to acquire the more dangerous strains relying on natural sources.

25

Abram S. Benenson, editor, Control of Communicable Disease Manual, 16

th

edition (Washington, DC: American Public

Health Association, 1995), pp. 20, 355.

26

Benenson, Control of Communicable Disease Manual, pp. 19, 380. Note, however, that in Sverdlovsk the incubation period

was 4 to 43 days and that a 9 to 10 day period was most common. See Meselson, et al., “The Sverdlovsk Outbreak of 1979,” pp. 1206-

1207.

27

A useful comparison of chemical and toxin agents is provided by David R. Franz, “Defense Against Toxin Weapons,” pp.

604-608, in Sidell, et al., Medical Aspects of Chemical and Biological Warfare.

28

Medical Management of Biological Casualties, Table 1, Appendix. At least one authority argues that the LD

50

is significantly

greater than commonly reported. According to William Patrick, who developed biological weapons for the U.S. Army in the 1950s and

1960s, the LD

50

for botulinum toxin through the inhalation route is 4.88 micrograms (a microgram is one millionth of a gram) for a 70

kilogram man (assuming 50% pure toxin). This translates to about 0.035 micrograms of pure toxin per kilogram of body weight, not 0.001

micrograms as usually reported. See Frederick R. Sidell, William C. Patrick, III, and Thomas R. Dashiell, Jane’s Chem-Bio Handbook

(Alexandria, Virginia: Jan’s Information Group, 1998), p. 179, and William C. Patrick III, “Potential Incident Scenarios,” p. I-60, in

Proceedings of the Seminar on Responding to the Consequences of Chemical and Biological Terrorism, July 11-14, 1995, sponsored by

the U.S. Public Health Service, Office of Emergency Preparedness, Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences, Bethesda,

Maryland. Other authorities cite a figure of 0.003 micrograms per kilogram of body weight for inhaled botulinum toxin. See John L.

Middlebrook and David R. Franz, “Botulinum Toxin,” p. 647, in Sidell, et al., Medical Aspects of Chemical and Biological Warfare.

29

At least one class of toxins, mycotoxins (the substances allegedly involved with the “yellow rain” attacks in Southeast Asia),

pose a dermal hazard because they can penetrate the skin. See Medical Management of Biological Casualties, pp. 75 and 100, and Robert

W. Wannemacher, Jr., and Stanley L. Weiner, “Tricothecene Mycotoxins,” pp. 658-659, in Medical Management of Biological Casualties.

30

Figure 30-1 in Franz, “Defense Against Toxin Weapons,” p. 606, in Sidell, et al., Medical Aspects of Chemical and

Biological Warfare.

14

Despite efforts to restrict the illicit acquisition of biological agents, it is likely that terrorists and

criminals will be able to obtain the agent that they want when they want it. If unable to acquire from a

legitimate culture collection or a medical supply company, they can steal it from a laboratory. If unable to steal

it, a group with the right expertise could culture the agent from samples obtained in nature. Many biological

agents are endemic, and a skilled microbiologist would have little difficulty culturing an agent from material

taken from nature.

Culture Collections: In 11 of the 33 cases involving acquisition, the non-state actors obtained

biological agents or toxins from legitimate suppliers. The American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) was the

source of the agent in at least two cases. Larry Wayne Harris obtained Y. pestis, while Kevin Birch and James

Cahoon acquired Clostridium botulinum and Clostridium tetani from this source. Benoyendra Chandra Pandey

obtained the Y. pestis from the stocks of a medical research institute that he used to murder his brother, but

only after several failed attempts to obtain it illicitly from the same source. The Rajneeshees purchased their

seed stock of Salmonella typhimurium from a medical supply company. Significantly, another group could do

the same today under current regulations, because the organism involved is not on any control list.

31

In any

case, the Rajneeshees had a state certified clinical laboratory, which gave them a legitimate reason to acquire

agents like the one that they used.

Theft: In four cases of the 33 cases involving acquisition, the perpetrators acquired their biological

agents by stealing them from research or medical laboratories. Almost all of the thefts involved people who

had legitimate access to the facilities where the biological agents were kept. J.A. Kranz, a graduate student in

parasitology, took the Ascaris suum eggs that he used against his roommates from the collections in the

university laboratory where he studied. Law enforcement officials believe that a laboratory technician removed

the Shigella dysenteriae Type 2 used to infect hospital laboratory technicians from the culture collection of the

hospital where she worked. Similarly, Dr. Suzuki stole S. typhi cultures from the Japanese National Institute of

Health, and reportedly used those cultures in preference to the ones he cultured himself from specimens taken

from typhoid patients. In only one of the reported incidents was an attempt made to infiltrate a laboratory to

steal a biological agent. It is alleged that the Weathermen group attempted to suborn an employee at the U.S.

military research facility at Ft. Detrick in order to obtain pathogens.

Self-manufacture: In six of the cases involving acquisition, the perpetrators manufactured the agent

themselves. In every reported case, the perpetrators produced ricin toxin by extracting it from castor beans. The

Minnesota Patriots Council, which produced a small quantity of ricin toxin, made it from a recipe found in a

book. In contrast, there were no successful attempts to grow C. botulinum to produce botulinum toxin.

Several readily available “how-to” manuals purport to describe techniques for producing botulinum

toxin or extracting ricin from castor beans. A considerable number of perpetrators have used The Poisoner’s

Handbook and Silent Death. Maynard Campbell’s Catalogue of Silent Tools of Justice, which is apparently no

31

The United States has implemented regulations that control the transfer of biological agents on a control list.

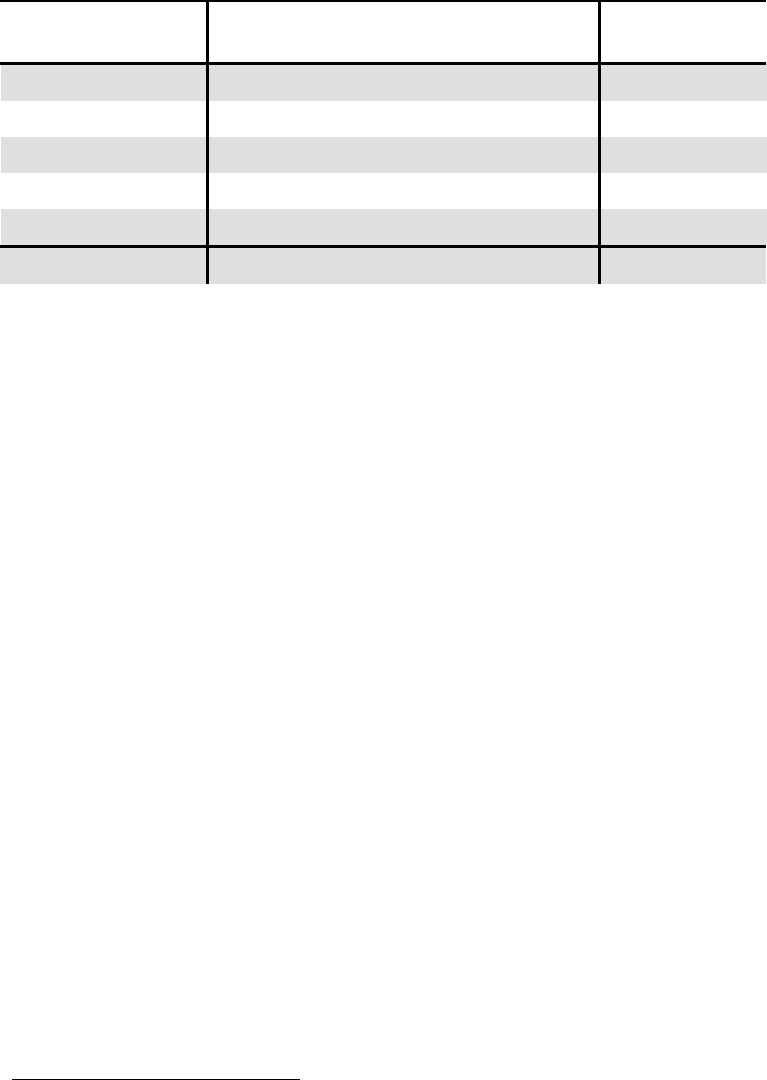

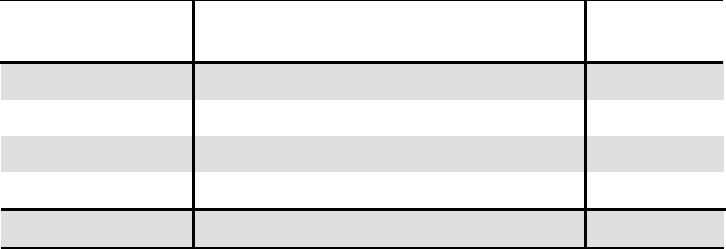

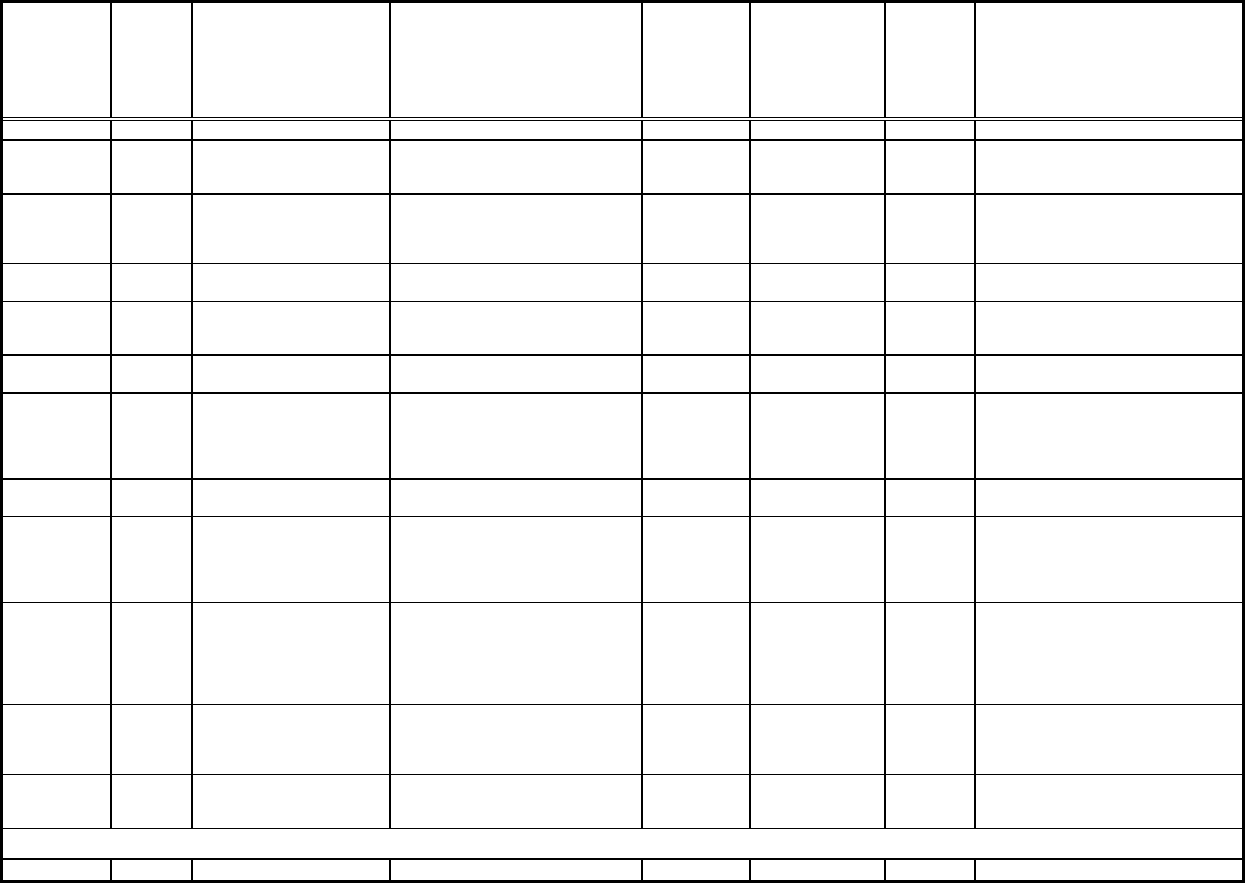

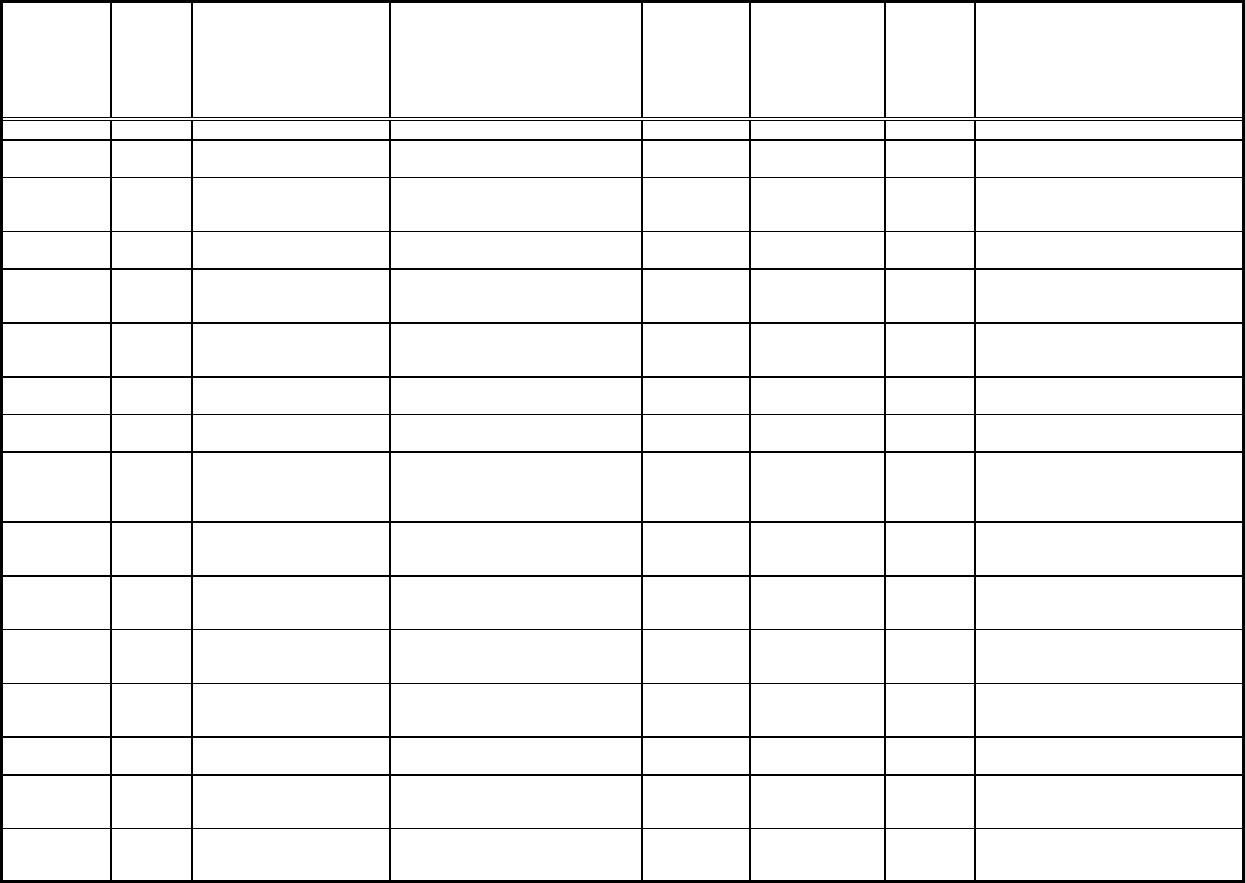

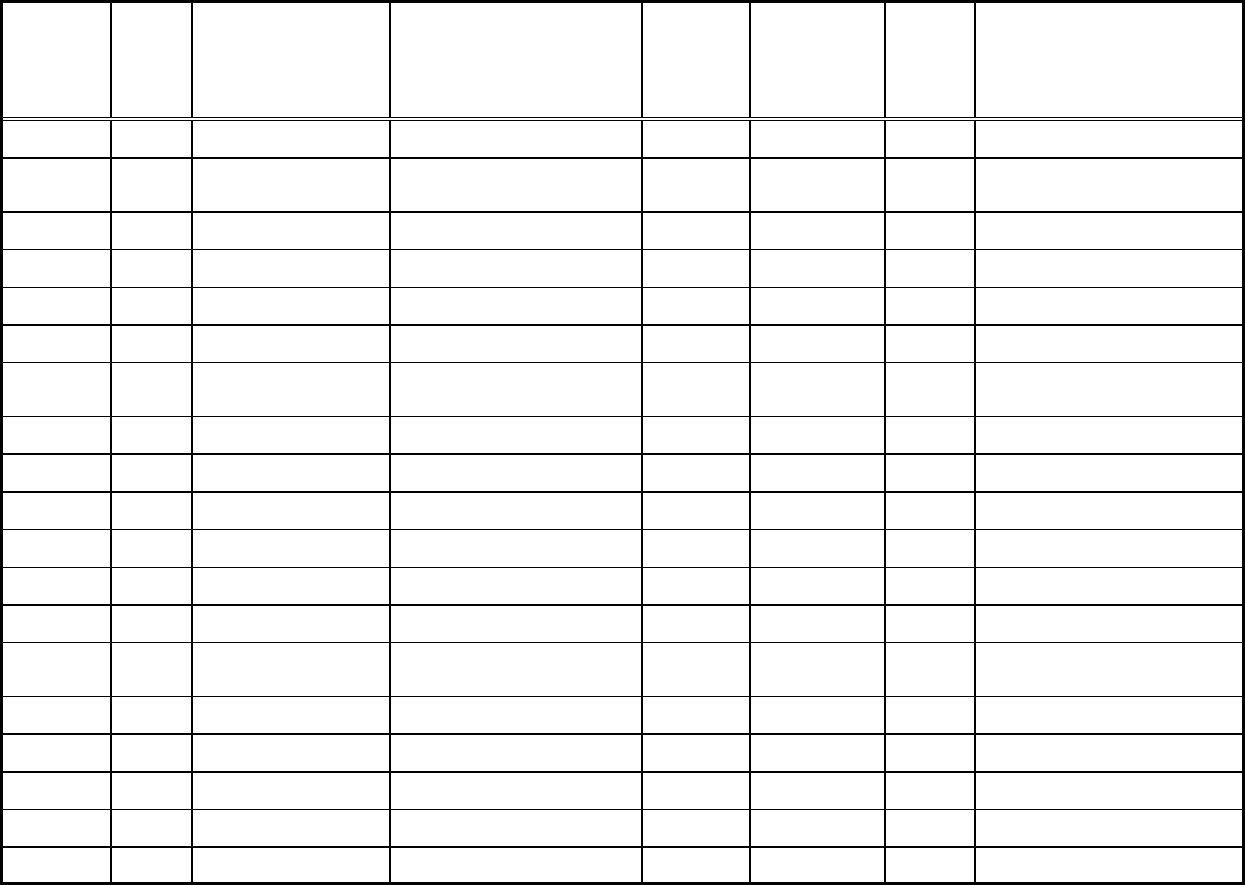

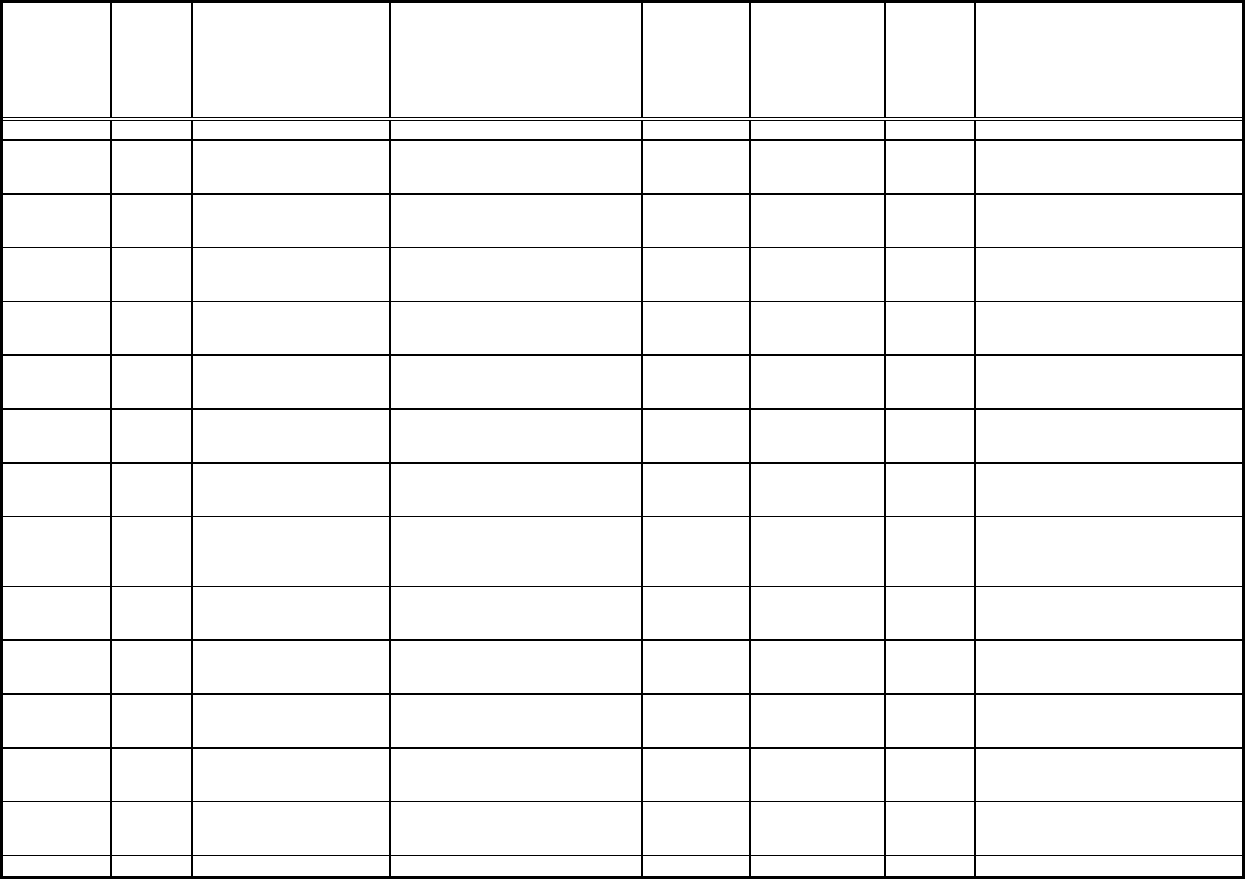

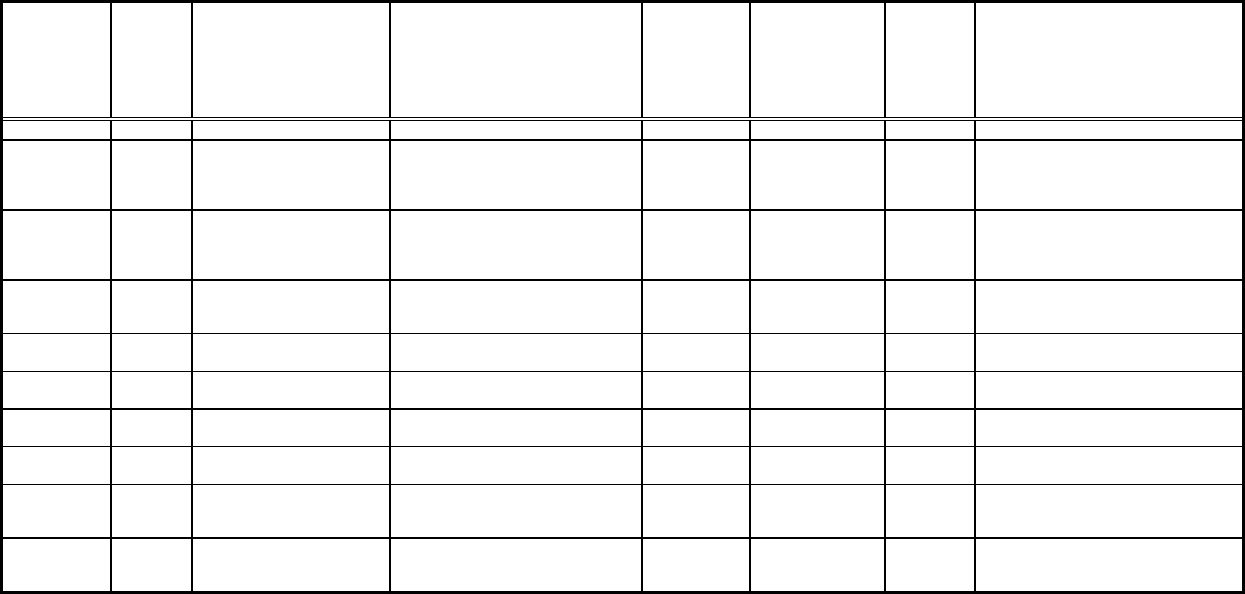

Table 4: Acquisition of biological agents

Type Terrorist Criminal Other/ Uncertain Total

Instances

Legitimate supplier 1 9 1 11

Theft 1 3 0 4

Self-manufactured 1 4 1 6

Natural source 2 4 0 6

Unknown 3 3 0 6

Total instances 8 23 2 33

Note: This table reflects the predominant method of acquisition; some individuals or groups

acquired agent through multiple paths.

15

longer in print, was used by the Minnesota Patriots Council in their ricin production. Long before the Internet,

perpetrators found it easy to obtain information about biological agents.

Natural: In six cases involving acquisition the biological agent was obtained from a natural reservoir

and transmitted without any processing. Some perpetrators apparently used castor beans, the seed containing

ricin, to poison people without attempting to extract the ricin from the bean. Similarly, in several cases the

perpetrators injected the victims with HIV-contaminated blood.

Types of agent actually acquired

Terrorists and criminals have shown an interest in both pathogens and toxins. In 129 of the 150 non-

state cases, the perpetrators threatened to use or considered pathogens. Note that few of these cases involved

actual possession. Some perpetrators considered multiple pathogens. In one instance, at least seven different

pathogens were involved.

Terrorists and criminals may not use the same agents as those selected by military biological weapons

programs. A comparison between the biological agents commonly considered suitable for military use and

those actually adopted by the perpetrators of the cases studied here is shown in Table 6. The objectives of the

terrorists will influence the selection of an agent, as will agent availability and the resources at the disposal of

the group for producing and disseminating the agent. This may lead to selection of unusual agents not

associated with state-sponsored biological weapons programs. Fortunately, many of the alternative agents are

unlikely to result in mass fatalities, even if they affect large numbers of people.

Bacterial agents: Approximately 125 of the cases focused on bacterial agents. B. anthracis appears

most often, and is associated with at least 113 cases, largely due to the growing popularity of anthrax threats.

Note that only three of cases involved possession of anthrax. Aum Shinrikyo may have had a stolen vaccine

anthrax strain incapable of causing harm to humans. Dark Harvest had anthrax-contaminated soil, but never

possessed the agent in a form likely to cause harm to people. Finally, the Polish Resistance apparently used

cultures stolen from laboratories with legitimate uses for the organism. Yersinia pestis, S. typhi, and Shigella

dysenteriae strains appear several times, while seven other pathogens appear no more than once.

Viral agents: Few perpetrators have considered viral agents, except when they can use it in a natural

state. HIV appears in 15 cases, including at least four murder cases. Six of the HIV cases involved extortion

threats in which in which there is no evidence of actual possession. In one case, the perpetrators employed a

viral agent, rabbit hemorrhagic disease.

Other pathogens: In only one case involved use of a parasite. In that case, the perpetrator

contaminated food with Ascaris suum, a worm that infects pigs and does not normally infect humans.

Toxins: In 27 of the 180 non-state cases, the perpetrators considered toxins. Ricin was considered in

14 cases. The next most common choice was botulinum toxin, which was an agent of choice in 9 cases.

Significantly, there is no reported example of successful production of botulinum toxin, despite claims that it is

easy to produce.

32

Other toxins include tetrodotoxin, an unknown mushroom poison, and an unspecified snake

toxin. In most cases, only a single toxin was involved. In one case, a group of murderers acquired the toxins

produced by Corynebacterium diphtheria and Vibrio cholerae.

32

Uncle Fester, Silent Death, Revised and Expanded 2

nd

Edition (Port Townsend, Washington: Loompanics Unlimited, 1997),

pp. 93-106.

Table 5: Type of agent involved

Type Terrorist Criminal Other/ Uncertain Total

Cases

Pathogen 15 38 83 136

Toxin 9 15 2 26

Unknown 4 1 1 6

Note: Because some perpetrators considered multiple agents, the totals in this table

exceed the total number of cases.

16

Combinations: In six cases, the perpetrators considered use of both pathogens and toxins. In three of

the cases, the perpetrator was interested in both B. anthracis and botulinum toxin. In another case, the

perpetrators thought about HIV and tetanus in addition to both B. anthracis and botulinum toxin. The last two

cases involved combinations that are more unusual: tetanus and botulinum toxin in one case, and S. typhi and

an unknown mushroom poison in another instance. In only two of these cases did the perpetrator acquire a

viable biological agent.

Employing Biological Agents

A biological agent is not necessarily a biological weapon. Only if there is a mechanism for spreading

the agent is it transformed into a weapon. Thus, a pathogen growing on a petri dish is not a weapon, or even a

threat, because it is unlikely to infect anyone. In some cases, the release method need not be very sophisticated.

If the agent is highly contagious, infecting a single person or animal may be sufficient to start an epidemic.

Disseminating biological agents in theory

When the agent is not contagious, as with many pathogens and all toxins, it is necessary to have a

dissemination mechanism that spreads the agent to the intended target. While it is possible to infect people by

injecting them one by one with biological agents, such a method is unlikely to prove attractive to most

Table 6: Biological agents involved

Traditional Biological Warfare

Agents

Agents associated with biocrimes

and bioterrorism

Pathogens Bacillus anthracis*

Brucella suis

Coxiella burnetii*

Francisella tularensis

Smallpox

Viral encephalitides

Viral hemorrhagic fevers*

Yersinia pestis*

Ascaris suum.

Bacillus anthracis*

Coxiella burnetii*

Giardia lamblia

HIV

Rickettsia prowazekii (typhus)

Salmonella typhimurium

Salmonella paratyphi

Salmonella typhi

Shigella species

Schistosoma species

Vibrio cholerae

Viral hemorrhagic fevers

(Ebola)*

Yellow fever virus

Yersinia enterocolitica

Yersinia pestis*

Toxins Botulinum*

Ricin*

Staphylococcal enterotoxin B

Botulinum*

Cholera endotoxin

Diphtheria toxin

Nicotine

Ricin*

Snake toxin

Tetrodotoxin

Anti-crop agents Rice blast

Rye stem rust

Wheat stem rust

* These agents appear in both lists.

17

terrorists. More likely, a terrorist will seek a technique to infect the entire target, whether people, livestock, or

crops, at one time.

Aerosol dissemination: Of greatest concern is the possibility that a terrorist might disseminate

biological agents as an aerosol cloud. In the context of biological warfare, the aerosol cloud should consist of

particles of 1-5 microns (one-millionth of a meter) in size. Particles much larger than 5 microns do not

penetrate into the lungs, since they are filtered out by the upper respiratory tract. In addition, they tend to settle

out of the air relatively quickly. In contrast, smaller particles do not remain in the lungs, but tend to be breathed

out.

33

Several considerations account for the concern about aerosol delivery. Many diseases are most

dangerous when contracted in this fashion. Thus, cutaneous anthrax, which is contracted through the skin, has

a case fatality rate of 5 to 20 per cent, though antibiotic treatment is highly effective. In contrast, inhalation

anthrax is usually fatal, and if not detected early there is no effective treatment. Similarly, Y. pestis is

responsible for substantially different diseases, including both bubonic and pneumonic plague. Bubonic plague,

generally acquired from the bite of an infected flea, has a case fatality rate of 50 to 60 per cent if untreated, but

generally responds to medical treatment. Pneumonic plague is also generally fatal if untreated. Early treatment

is essential to save those infected. Pneumonic plague is considered highly contagious, while bubonic plague is

not.

34

Aerosol transmission also makes it possible to spread biological agents over a large area and thus

affect a large number of people in one attack. The Office of Technology Assessment calculated that 100

kilograms of anthrax spread over Washington could kill from one to three million people if disseminated

effectively under the right environmental conditions. In contrast, a one-megaton nuclear warhead would kill

33

Edward M. Eitzen, “Use of Biological Weapons,” p. 440, in Sidell, et al., Medical Aspects of Chemical and Biological

Warfare.

34

Benenson, Control of Communicable Disease Manual, pp. 18-19, 353. A recent review of the anthrax threat, however, notes

that the survival data predates the creation of hospital intensive care units, and suggests that more people might survive under

contemporary conditions than usually stated. See James C. Pile, John D. Malone, Edward M. Eitzen, and Arthur M. Friedlander, “Anthrax

as a Potential Biological Warfare Agent,” Archives of Internal Medicine, Vol. 158 (March 9, 1998), pp. 429-434. Significantly, there were

11 identified survivors of inhalation anthrax from the Sverdlovsk release, suggesting a case fatality rate of only 85 per cent.

Table 7: Biological Agent Attack on City of 1,000,000 people

Disease Caused by Agent Number of People at Risk Deaths Incapacitated

Only

Anthrax 180,000 95,000 30,000

Brucellosis 100,000 400 79,600

Epidemic typhus 100,000 15,000 50,000

Plague 100,000 44,000 36,000

Q fever 180,000 150 124,850

Tularemia 180,000 30,000 95,000

Venezuelan equine encephalitis 60,000 200 19,800

Source: World Health Organization, Health Aspects of Chemical and Biological Weapons (Geneva: World Health Organization, 1970), pp. 95-99.

The WHO model assumes a city of 1,000,000 people in a developed country, and makes assumptions regarding the population distribution

around a high density urban core that may no longer be appropriate. The model also makes certain assumptions about the agent (50 kilograms of

dried powder containing 6 × 10

15

organisms disseminated in a line 2 kilometers long at a right angle to the wind direction. The model nominally

illustrates dissemination from an aircraft, but none of the calculations appears to depend on the type of the delivery vehicle involved. As an

example, the model assumes that the Venezuelan equine encephalitis will survive for only about 5-7 minutes, during which time it will travel

about 1 kilometer. About 60,000 people will be exposed to the agent. About 20,000 people will become incapacitated, including 200 who will

die. In contrast, anthrax will survive for more than two hours and will travel for more than 20 kilometers. At least 180,000 people will be exposed

to the agent, including 30,000 who will become incapacitated and 95,000 who will die.

18

from 750,000 to 1.9 million people.

35

An alternative set of calculations was prepared for a study by the World

Health Organization (WHO). According to estimates prepared by WHO’s expert panel, 50 kilograms of dry

anthrax used against a city of one million people would kill 36,000 people and incapacitate another 54,000.

36

Water contamination: Many pathogens that have had a significant impact on human life, such as

Vibrio cholerae (which is the organism responsible for cholera) and Salmonella typhi (which causes typhoid

fever), are water-borne. It is also possible to inject toxic substances into water systems, including toxins. Thus,

it is not surprising that some terrorist groups interested in biological agents have targeted municipal water

systems.

37

Fortunately, water systems are less vulnerable than often thought. Municipal water systems are

designed to eliminate impurities, especially pathogens. As part of this process, communities use filters to

remove particles from the water and add chlorine to kill any organisms that remain. In addition, the ID

50

for

diseases spread through water is often extremely high. One test indicated that only half of persons who

ingested 10

7

(10 million) S. typhi organisms became ill.

38

According to a Department of Defense biological

warfare analyst, it would require “trainloads” of botulinum toxin to contaminate the New York City water

supply to cause problems, simply because of the extent to which the toxin is diluted.

39

For all these reasons,

infecting a large population through deliberate contamination of water supplies is difficult to accomplish.

Food contamination: Terrorists also have spread biological agents by contaminating food. In

general, only uncooked or improperly stored food is vulnerable, because the heat generated during cooking

readily destroys most pathogens and toxins. This implies that a terrorist would need to target foods that are

commonly eaten uncooked, or that can be contaminated after being cooked. Alternatively, the terrorists would

need to rely on a toxin that survives cooking.

The dangers from deliberate contamination of food have probably grown due to fundamental changes

in food distribution systems. The food processing industry has become increasingly centralized, so that

contamination introduced at a single facility can affect large numbers of people. In addition, an increasing

amount of food is imported, raising the prospect that perpetrators operating in a foreign country might be able

to contaminate food eaten in the United States.

40

Direct application: The most reliable way to infect someone is to inject the victim with the

organisms responsible for causing a disease. This technique avoids most of the technical problems associated

with the dissemination of biological agents. Similar techniques can be used with toxins. In addition, some

toxins can cause harm even if applied on the skin.

35

U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction: Assessing the Risks, OTA-

ISC-559 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, August 1993), pp. 53-54.

36

This calculation assumes a 50 per cent reduction in fatalities due to prompt administration of antibiotics. It also excludes

people who might be infected more than two hours after agent release. World Health Organization, Health Aspects of Chemical and

Biological Weapons (Geneva: World Health Organization, 1970), pp. 98-99.

37

For a review of the risk to municipal water systems, see World Health Organization, Health Aspects of Chemical and

Biological Weapons, pp. 113-120.

38

World Health Organization, Health Aspects of Chemical and Biological Weapons, p. 115.

39

Testimony by Dr. Barry Erlick, p. 38, in United States Senate, Committee on Governmental Affairs, Permanent

Subcommittee on Investigations, Global Spread of Chemical and Biological Weapons (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office,

1990).

40

Janice Rosenberg, “Attack of the killer shellfish, raspberries, hamburgers, milk, poultry, eggs, vegetables, potato salad,

pork….” American Medical News, May 4, 1998, pp. 12-15.

19

Insect vectors: Many diseases are naturally transmitted by insects. For example, plague is transmitted

by certain flea species, yellow fever is carried by one specific mosquito species, Aedes aegypti, and typhus is

spread by the body louse, Pediculus humanus corporis. It is thus not surprising that biological warfare experts

have considered insects as potential vectors for biological agents. The Japanese biological warfare program

devoted considerable effort to this dissemination route. On at least a few occasions, the Japanese to have used

infected fleas to spread plague.

41

The United States considered use of mosquitoes to disseminate certain

agents, and established a facility to breed the needed mosquitoes.

42

Insect vectors posed problems: they were

difficult to control, and their use was likely to create disease reservoirs in the area where the insects were

released.

Dissemination in practice

There is a substantial difference between the theory and practice of bioterrorism. The technical

obstacles associated with the use and dissemination of biological agents are considerable, and should not be

underestimated. Even individuals with considerable technical expertise often find that it is difficult to work

with biological agents, even when using relatively simple dissemination techniques.

Aerosolization: Only two groups are known to have considered aerosolization of biological agents:

Aum Shinrikyo and R.I.S.E. Neither group mastered the requisite technology. According to published

accounts, the Aum Shinrikyo attempted to disseminate both B. anthracis and botulinum toxin on multiple

occasions. They are not known to have caused any casualties.