UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation

Implementing the Backyard

Revolution:

Perspectives of California’s

ADU Owners

| APRIL 22, 2021 |

The Center for Community Innovation (CCI) at UC

Berkeley nurtures effective solutions that expand

economic opportunity, diversify housing options, and

strengthen connection to place.

Center for Community Innovation

c/o Institute of Governmental Studies

109 Moses Hall, #2370

Berkeley, CA 94720-237

Authors

Karen Chapple, Ph.D., Dori Ganetsos, and Emmanuel Lopez

Acknowledgements

We thank the California Department of Housing and Community Development and Baird + Driskell

Community Planning for funding this research. We are grateful to Julia Greenberg of the Center for

Community Innovation, as well as David Garcia and Ben Metcalf of the Terner Center of Housing

Innovation, for their review and feedback. We also thank Audrey Lieberworth, Isaac Schmidt, and

Rachel Schten for their research assistance.

Cover photo courtesy of PreFab ADU

About the California Department of Housing and Community Development

The Department awards loans and grants to public and private housing developers, nonprot

agencies, cities, counties, and state and federal partners. The Department also develops housing

policy, building codes, and regulates manufactured homes as well as mobile home parks.

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 3

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation - April 2021

Accessory dwelling units (ADUs) are an increas-

ingly popular housing type seen as a way to fos-

ter inll housing development, increase the hous-

ing supply without altering existing neighborhood

character, provide multigenerational housing

options, and generate supplemental income for

homeowners. This report presents the ndings

from the rst-ever statewide ADU owner survey

in California.

Homeowner Characteristics

• Homeowners with an ADU are much more af-

uent and less likely to identify as Hispanic or

Latine than the typical Californian homeown-

er.

• The top challenges that property owners face

in building an ADU are the local approval pro-

cess, design constraints or challenges, and

the cost of construction.

Physical ADU Characteristics

• Almost all property owners in our sample

(97%) only have one ADU on their property.

• The majority of new ADUs (53%) in California

are detached units.

• The average square footage of new ADUs in

the state is 615 square feet (sf), with minor

regional variation.

• The majority of California’s new ADUs (61%)

contain just one bedroom, with studio units

being the second most popular unit typology

(18%). Units with two or more bedrooms only

account for 21% of the ADUs in the state.

Local Approvals

• Half (50%) of homeowners found it difcult to

obtain an ADU permit. The same percentage

of homeowners found it difcult to build their

ADUs to their jurisdiction’s development stan-

dards.

Construction

• The median statewide construction cost of an

ADU is $150,000, or $250/square foot.

• A signicant portion of ADUs (37%) cost less

than $100,000 to build, and 71% of ADUs cost

less than $200,000 to construct.

• ADUs in the San Francisco Bay Area region

are the most expensive to build, with a me-

dian construction cost of $177,500 ($329/sf).

In the Central Coast region the median con-

struction cost is $140,000 ($223/sf), followed

by $130,000 ($200/sf) in Orange and San Di-

ego Counties, and $100,000 ($197/sf) in Los

Angeles County.

• We found notable per square foot cost varia-

tion of the ADUs in our sample based on the

unit type, number of bedrooms, type of nanc-

ing used to construct these ADUs, and house-

hold income of the property owner.

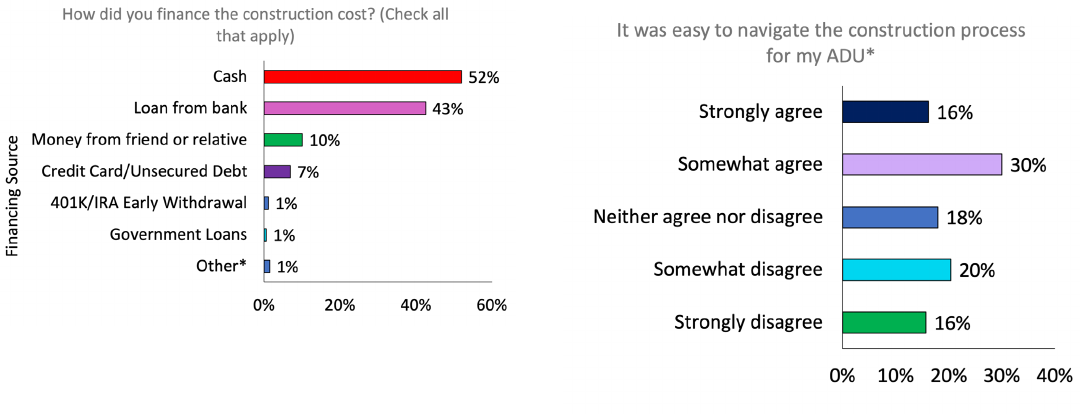

• Homeowners used some combination of the

following nancing schemes, though the pro-

portions of which were not captured in the

survey, to construct their ADUs: cash (53%),

loans from a bank (43%) and money from

friends or relatives (10%).

Rental Tenure

• About half (51%) of California’s new ADUs

serve as income-generating rental units, and

Executive Summary

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 4

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation - April 2021

16% of ADUs provide no-cost housing to a

relative of the homeowner.

• Only 8% of new ADUs in California are

short-term rentals, though more afuent

homeowners are more likely to list their ADUs

as short-term rentals than those making less

than $100,000 a year.

• California’s new ADUs typically do not result

in family-sized rental units; in fact, 86% of the

state’s renter-occupied ADUs have just one or

two people living in them. However, 21% of

the occupied ADUs owned by property own-

ers earning less than $100,000 a year housed

three or more people, compared to just 6% of

the ADUs owned by property owners making

over $100,000 a year.

• Very few new ADUs provide housing for

school-aged children (11%) or senior citizens

(15%).

• Of the tenant-occupied ADUs, 40% of tenants

do not park any cars on the street and 46%

park just one car on the street.

Rental Prices

• The median rental price of an ADU in Califor-

nia is $2,000, ranging from $1,925 in the Cen-

tral Coast region to $2,200 in the San Francis-

co Bay Area.

• The median ADU rent per square foot in the

state is $3.68.

• The overall affordability of ADUs varies by

region. The median rental price of an ADU

is affordable (less than 30% of household in-

come) to the median household of two people

in the San Francisco Bay Area and the Cen-

tral Coast regions.

• In the counties where we received greater than

20 total survey responses from landlords of new

ADUs, we found that a large portion of units are

available to those making less than 80% of the

area median income (AMI), though the over-

all affordability varies signicantly by county.

Moving Forward

ADUs do provide relatively affordable rental

housing units for Californians, conrming our

previous research. But there are still signicant

barriers to making these a widespread policy

solution for tackling the state’s affordable hous-

ing crisis. This survey suggests that despite leg-

islative reforms, the ADU revolution has been

slow to reach low-income homeowners of color.

It will take a targeted effort at both the state and

local level to meaningfully boost ADU production

throughout the state and to eliminate structural

barriers to ADU production so that all Californians

can reap the benets.

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 5

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation - April 2021

Introduction

Accessory dwelling units (ADUs) have grown from

a relatively obscure housing type to a popular tool

to foster inll housing development, increase the

housing supply without altering existing neigh-

borhood character, provide multigenerational

housing options, and generate supplemental in-

come for homeowners. In California, planners

and policymakers promote ADUs as a means to

combat the state’s housing crisis. In recent years,

the California State Legislature passed a suite of

ADU legislation seeking to reform prohibitive zon-

ing and land use regulations at the local level in

order to bolster ADU production statewide. As a

result, California has seen 9,000 ADUs complet-

ed in just the years 2018 and 2019.

1

In response

to this new state initiative, some local govern-

ments promote ADUs as a way to subtly densify

housing supply; nonprot organizations advocate

for broader ADU production; and startups pro-

duce prefabricated ADUs for homeowners. It is

time for reection: how do homeowners view the

revolution in their backyards?

This report presents the results of the rst survey

of California-based homeowners with an ADU. It

is important for policymakers, planners, and gov-

ernment ofcials to understand the experiences

of those with an ADU on their properties to learn

how best to support the production of ADUs as a

means to alleviate the state’s affordable housing

crisis.

We begin with a summary of our research

methodology, and then present the ndings of

our comprehensive ADU homeowner survey,

including new data on the characteristics of the

property owners who completed our survey, the

physical characteristics of their ADUs, local ap-

provals, the construction process, and ADU -

nances (construction costs and rents charged by

ADU type). We then conclude with a discussion

on the policy implications of our ndings, limita-

tions of our data, and areas for future ADU re-

search.

Methodology

In order to collect information from homeowners

with an ADU on their property, we developed and

administered a digital survey in both English and

Spanish (see Appendix A for full survey text, and

Appendix B for high-level survey results). We

used the California Department of Housing and

Community Development’s (HCD) Annual Prog-

ress Report (APR) database of properties that

applied for an ADU permit or received a Certi-

cate of Occupancy for an ADU in the year 2018

or 2019 to identify our survey recipients. We sup-

plemented our APR database with a list of ADUs

completed in certain Bay Area jurisdictions pro-

vided by a private planning rm.

2

In late Summer to Fall of 2020, 15,745 house-

holds in California received postcards inviting

them to complete our digital survey. 823 of our

postcard recipients took the survey, resulting in

a 5.23% response rate. After eliminating respon-

dents who were not the owner of a property with

an ADU on it, our nal response rate was 4.8%.

Please see Appendix C for a detailed methodolo-

gy outlining our postcard distribution process and

acknowledged survey response biases.

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 6

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation - April 2021

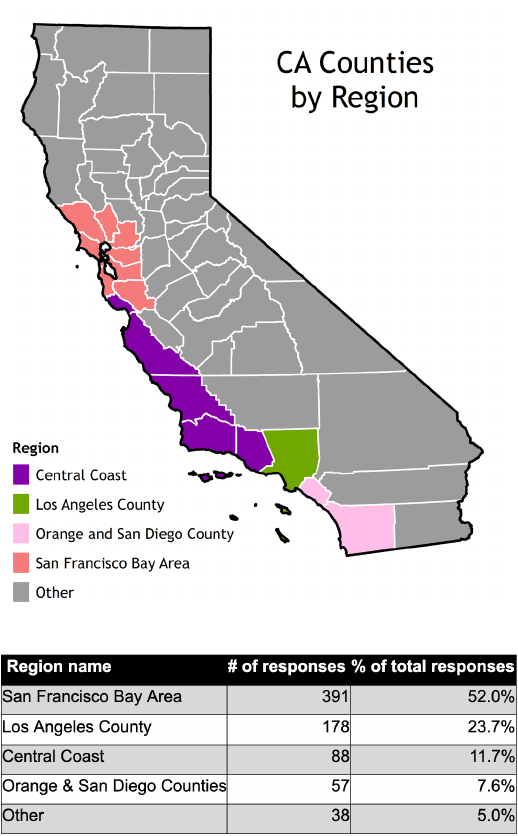

Given our relatively limited sample size, we an-

alyze all homeowner responses based on geo-

graphic region. Our regions with sufcient sample

size for analysis included the San Francisco Bay

Area, Los Angeles County, the Central Coast,

and Orange and San Diego Counties (Figure 1).

We categorize the remaining 38 respondents that

were outside of those four regions as “other”, and

include them only in our overall survey analysis.

Figure 1: Map of regions

Table 1: Responses by region

We also compare some of our ndings to

state-level American Community Survey (ACS)

data to contrast our sample of homeowners with

an ADU to Californians in general. Of note, “con-

struction costs,” as used in this report, refers to

the total cost that the homeowner spent on their

ADU, and is inclusive of all costs for design, la-

bor, materials, and permits.

Findings

In this section, we present key survey ndings

regarding the characteristics of property owners

with an ADU, physical characteristics of ADUs in

the state, homeowners’ perspectives of the local

approvals process, nancing used to build ADUs,

homeowners’ opinions on the construction pro-

cess, rental tenure, and ADU rental prices. Where

relevant, we analyze these results by region; the

ADU type and number of bedrooms in the unit;

the method of construction nancing; and the in-

come of the property owner.

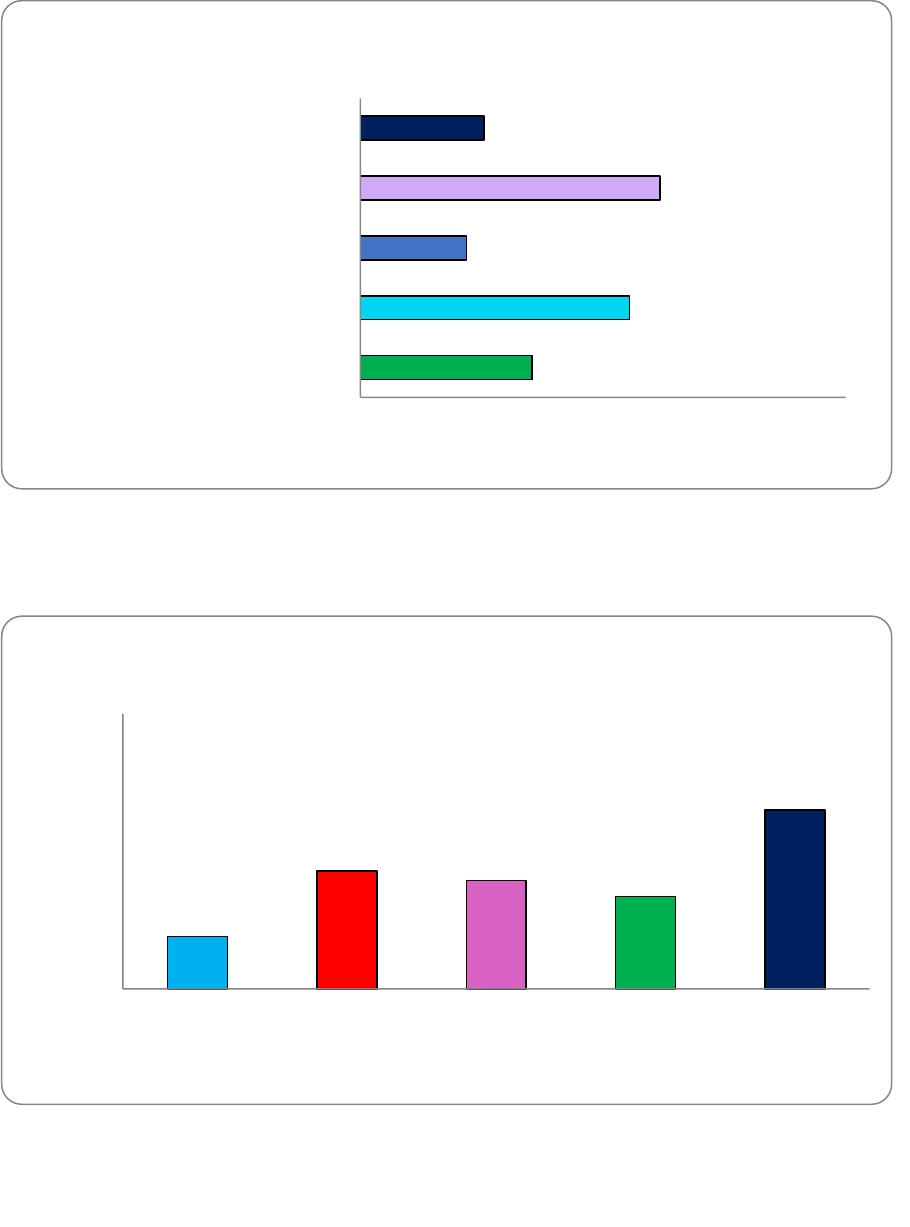

Property Owner Characteristics

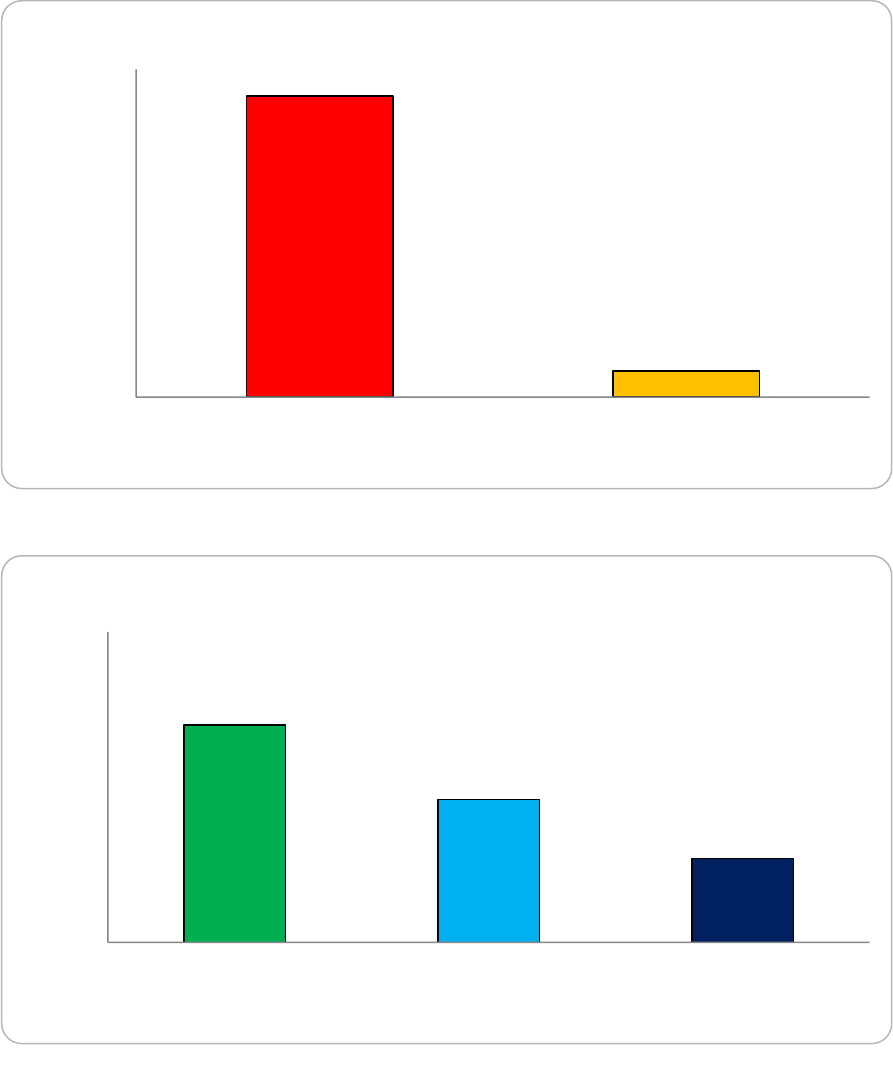

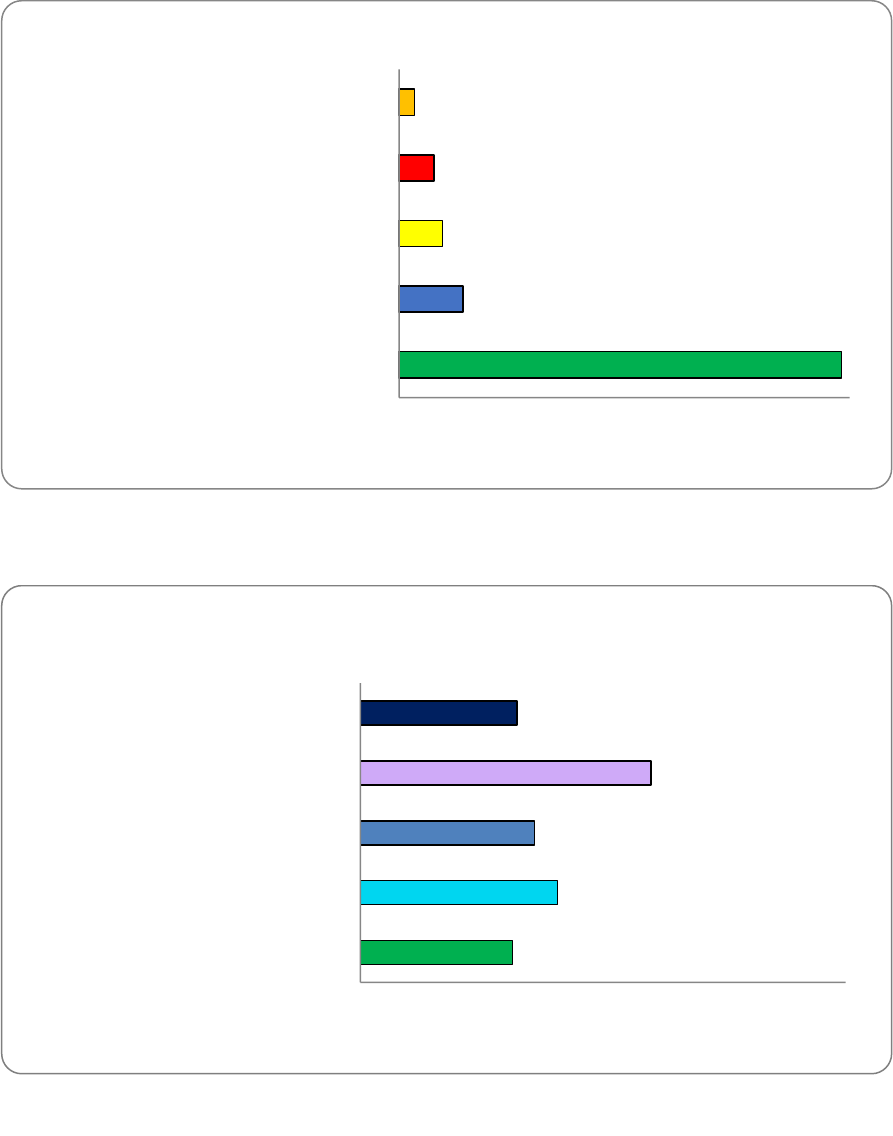

Property owners with a new ADU on their prop-

erty are more afuent than the typical home-

owner in California, where the median income

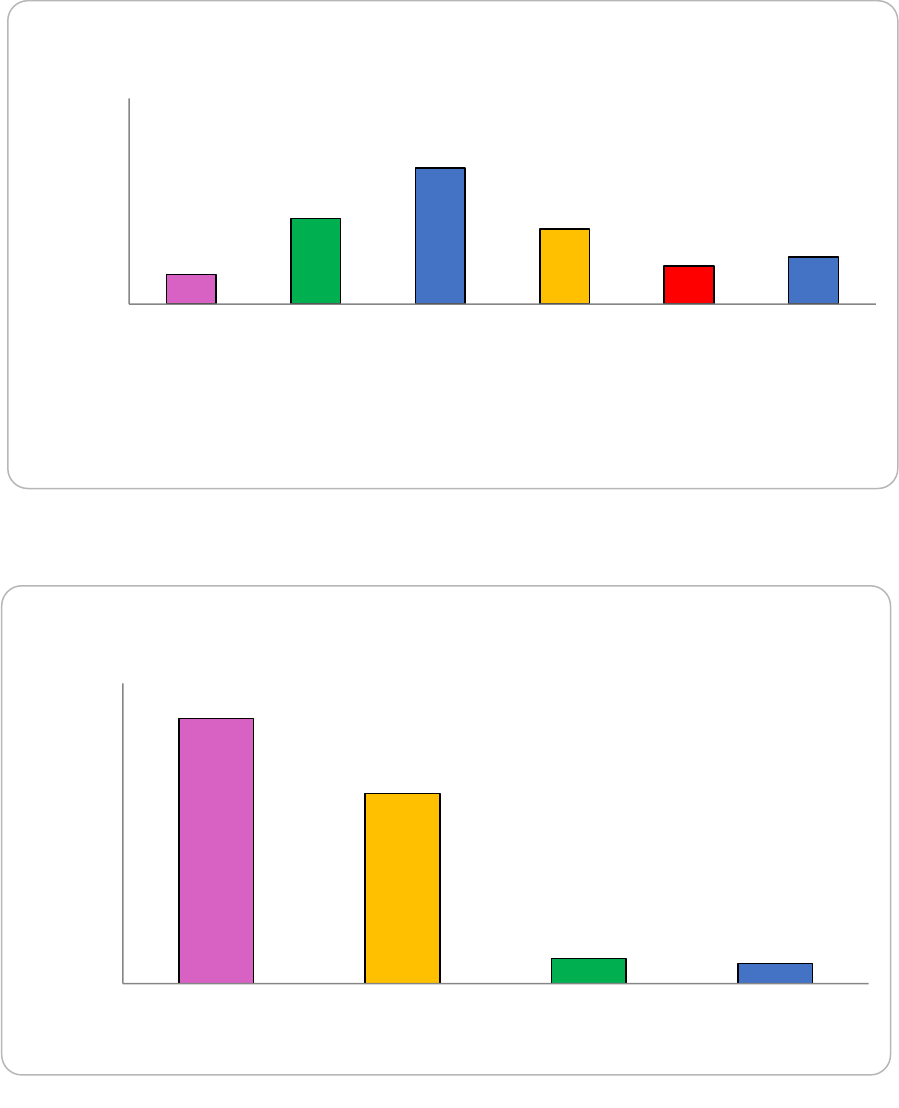

is $103,870. As shown in Figure 2, 33% of our

survey respondents reported having a house-

hold income over $200,000, compared to 14%

of all Californians in 2019; 70% of respondents

earned an income of $100,000 or more, com-

pared to 40% of Californians.

3

One potential

explanation for this is the large concentration

of respondents who live in California’s coastal

regions, which tend to have a higher area me-

dian income (AMI) than other parts of the state.

Additionally, 52% of our survey respondents

lived in the San Francisco Bay Area, which has

some of the highest incomes in the state. None-

theless, this suggests that there may not be

adequate nancing options for lower- to mod-

erate-income households to construct an ADU.

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 7

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation - April 2021

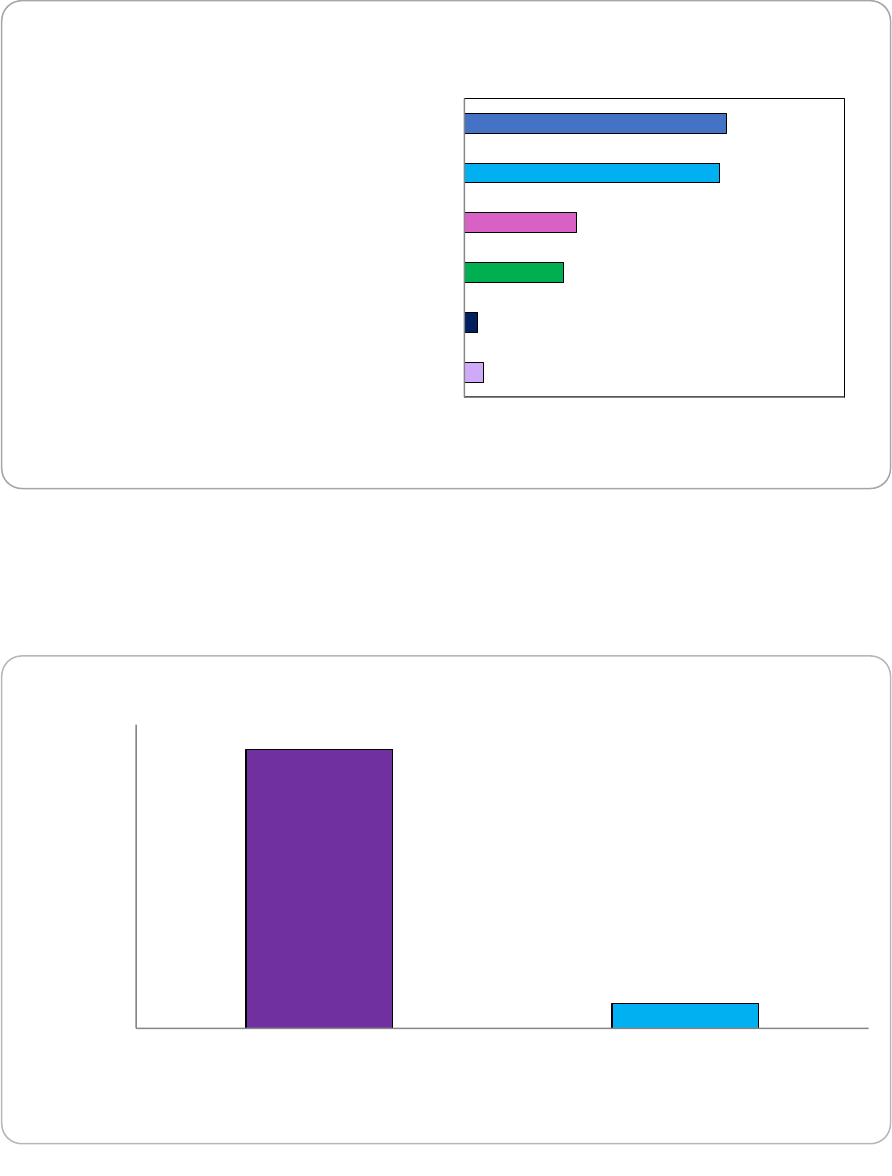

The racial composition of homeowners that

constructed an ADU is similar to the race of

California’s homeowners, with 71% of our

survey respondents identifying as White,

compared to 69% of homeowners in the

state (Figure 3). However, we did nd lower

Figure 2: Household Incomes of survey respondents versus Californian median household

incomes

representation of survey respondents who iden-

tify as Hispanic or Latine (14%) than the average

Californian homeowner (29%). Overall, then, the

development of ADUs to date has not been equi-

table across ethnic and class lines, much like the

ability to attain homeownership in the state.

Figure 3: Race of survey respondents versus all owner-occupied units in California

n of Survey Respondents = 694

n of California Owner-Occupied Units = 7,218,742

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 8

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation - April 2021

The homeowners who did successfully build an

ADU were forthcoming regarding the benets

that these units provided to their families. One

shared that building an ADU “was one of the

best decisions I’ve made to help my family”,

while another respondent noted that “my ADU

enabled me to retire at age 62 which was

medically necessary.” A third elaborated more

on the benets of building an ADU for her family:

Many of our survey respondents shared simi-

lar stories, noting that their units provide private

housing for live-in caregivers; preserve cultur-

al connections by housing family members who

speak their native language; allow elderly home-

owners to downsize while still aging-in-place; and

enable them to take care of their aging parents.

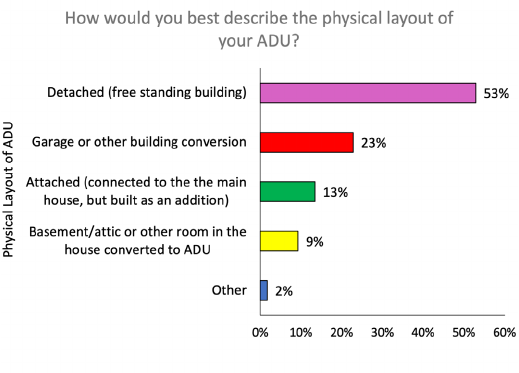

Physical ADU Characteristics

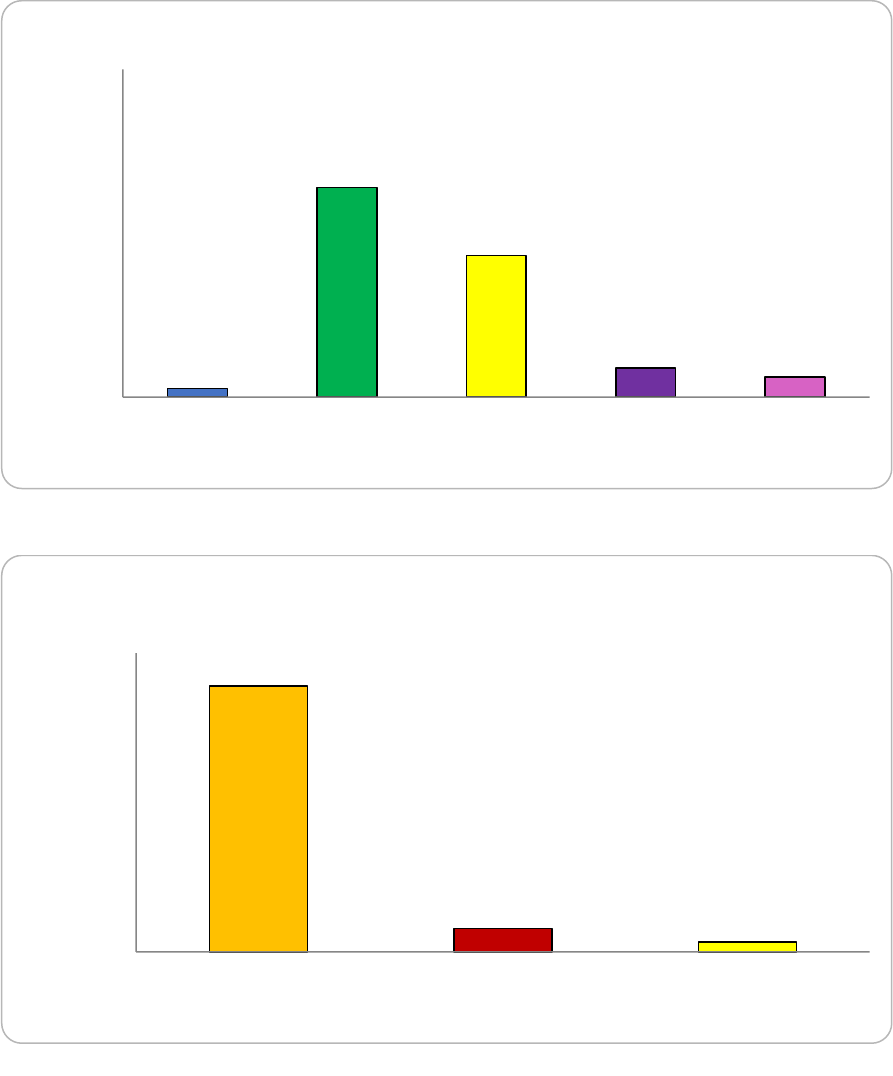

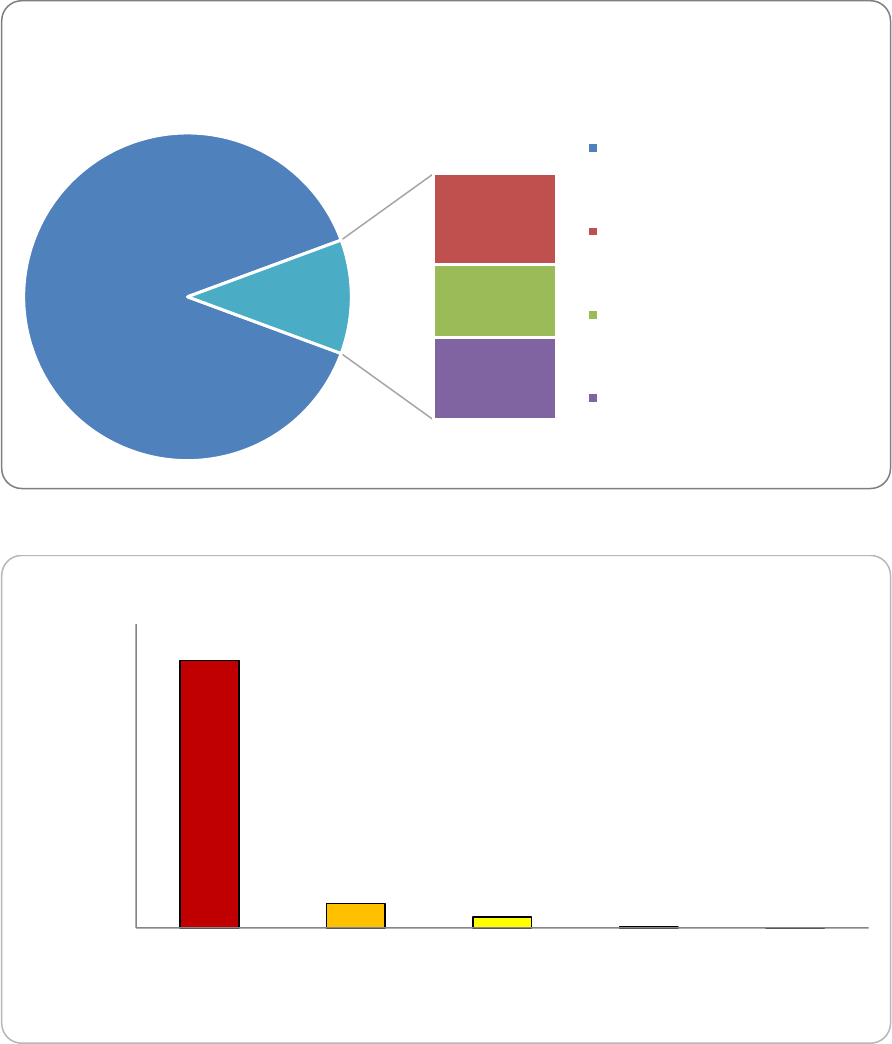

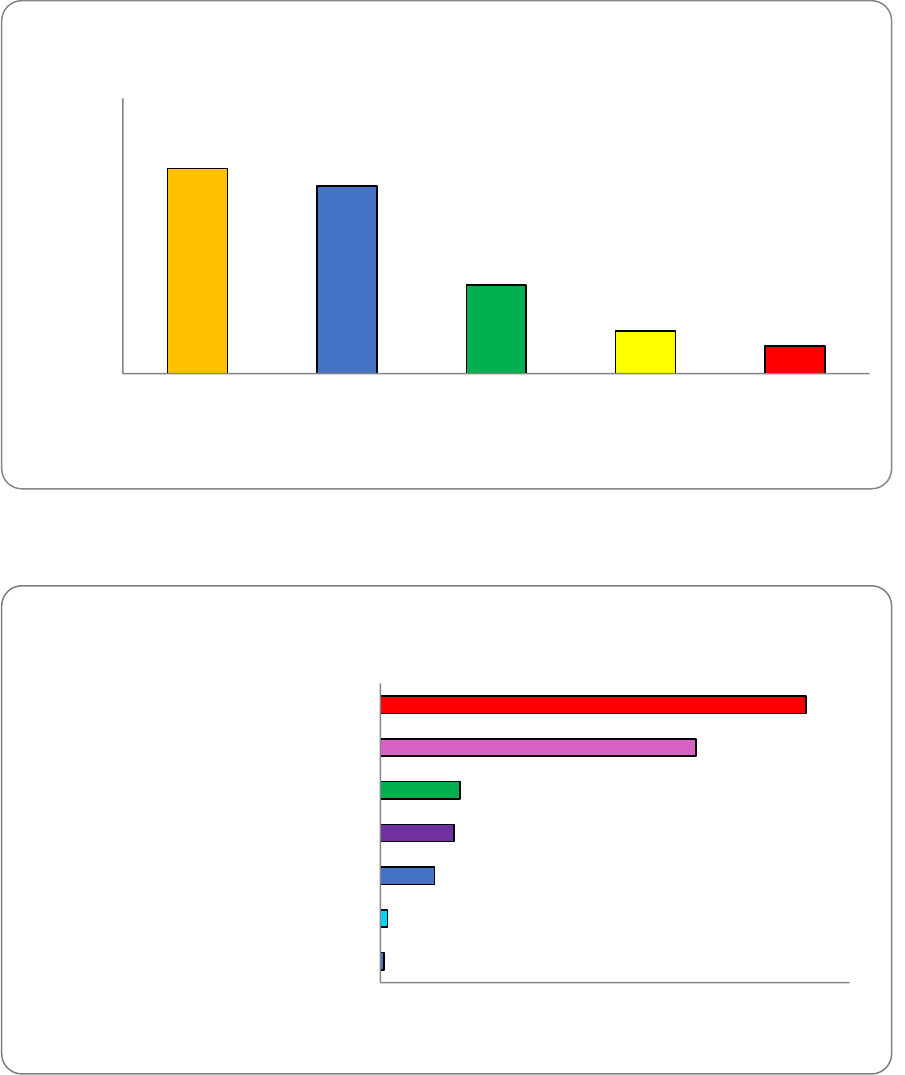

Until January 1, 2020, the State Legislation only

required jurisdictions to permit one ADU on lots

with a single-family home; thus, unsurprisingly,

97% of those with a completed ADU have only

one. Of these ADUs, the majority (53%) are new

construction detached units, while 23% use ex-

isting spaces from, or add new square footage

to, existing detached garages or accessory struc-

tures. Less commonly, homeowners have built

ADUs as additions attached to the main home

(13%) or converted space from the main dwelling

unit (9%) (Figure 4). The popularity of detached

units may be attributed to the amount of privacy

that these ADUs provide to homeowners, com-

pared to attached or converted ADUs where the

unit shares a wall with the primary residence.

Figure 4: Unit typologies

Although jurisdictions typically allow “generous

ADU sizes” on paper,

4

the average ADU is just

615 square feet, with some regional variation.

Homeowners in Orange and San Diego Counties

built the largest ADUs (694 sf), followed by home-

owners in Los Angeles County (621 sf). ADUs in

the San Francisco Bay Area (604 sf) and the Cen-

tral Coast (600 sf) were the smallest. Many juris-

dictions impose size restrictions on ADUs based

on the square footage of the main residence, as

noted by one of our survey respondents: “one of

the challenges was being limited to the ADU

size because of the size of the main house.

The requirement was that the ADU could not

exceed 50% in size of the main house which is

only 1,286 square feet, thus limiting the ADU

“the cost of renting apartments is so

high and prohibitive in the Bay Area,

therefore having a separate unit for the

adult children is a great way of keeping

the family together in a nancially and

socially economical way. The family

stays together, yet everyone has pri-

vacy and independence. We have the

ability to rent it out in the future as well.

But children not being stretched and

stressed to afford housing while work-

ing in the Bay [A]rea is a good thing for

everyone.”

n = 724

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 9

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation - April 2021

to 643 square feet.” Additionally, zoning tools

including lot coverage, oor area ratios (FAR),

height limitations, and front setbacks work to limit

the maximum size of ADUs on top of the stated

maximum size limitations, though many of these

limitations are now prohibited -- to an extent --

per the State Legislation.

5

The majority of California’s ADUs (61%) contain

just one bedroom, while studios are the second

most common unit type (18%). Units with two

bedrooms only account for 17% of the ADUs in

the state, and only 3% of the state’s ADUs contain

three or more bedrooms. This is consistent with

the ndings of an earlier ADU survey of home-

owners in Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver, in

which 81% of the ADUs were either one-bedroom

or studio units.

6

Minimum dwelling unit sizes im-

posed at the local level, in conjunction with the

limits on the total square footage of ADUs, likely

contribute to the number of bedrooms that home-

owners ultimately build.

Local Approvals

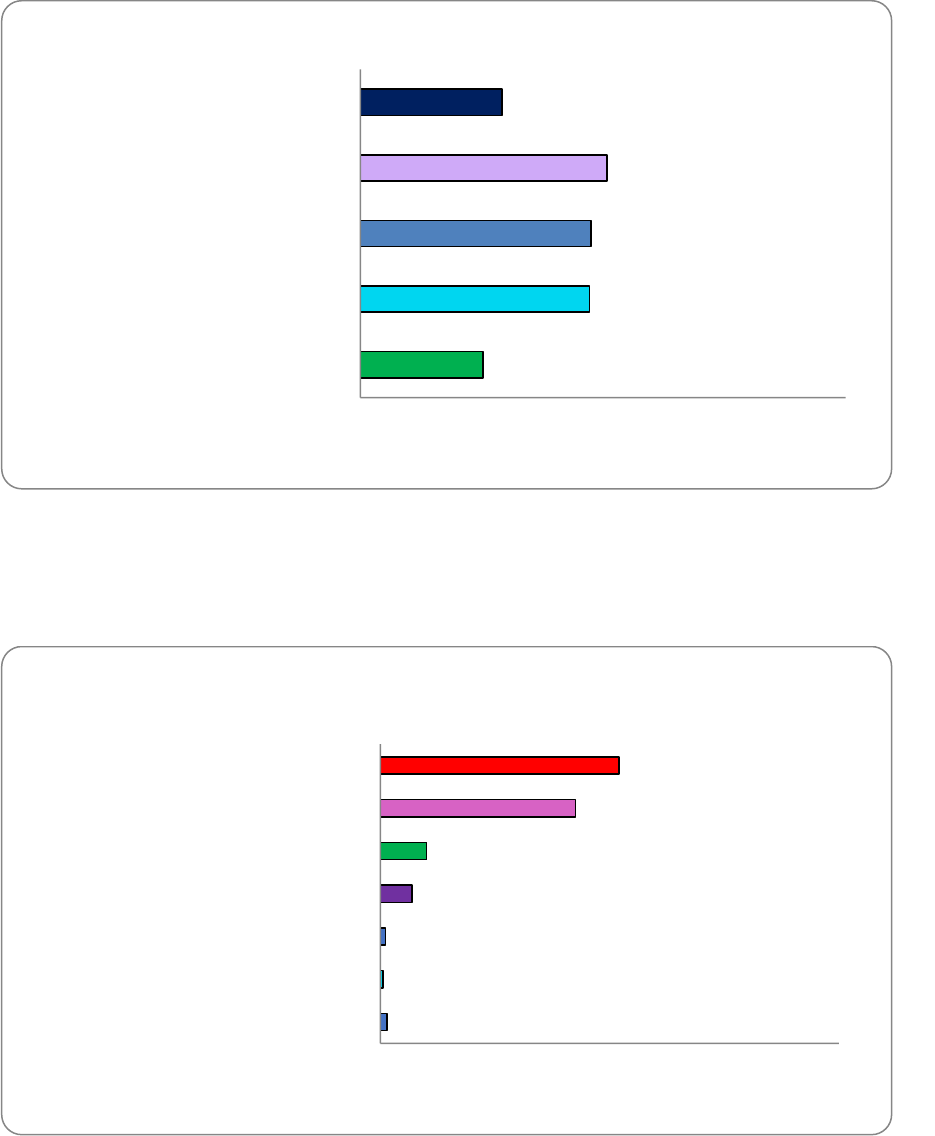

Across the state, homeowners had quite differ-

ent experiences designing and obtaining approv-

al for their ADUs. Local zoning reforms were the

top factor that made it possible for homeowners

to build their ADUs: 28% of our survey respon-

dents pointed to these reforms as enabling them

to construct their units. Some homeowners said

that their local jurisdictions made it fairly easy for

them to obtain the necessary ADU permits, not-

ing that they “did not have to go to planning

commission, which saved $$$$$ and TIME,”

“the permitting process went relatively quick-

ly and smoothly,” and that “the ease and cost

of permits’’ was a particularly positive aspect of

their ADU project.

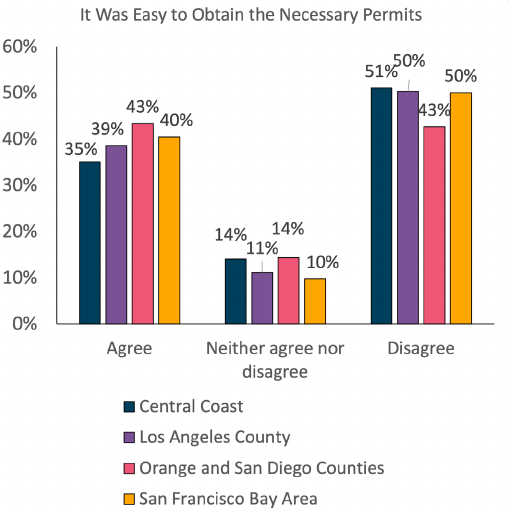

But for many, obtaining local approval to build

an ADU was the top challenge associated with

adding an ADU. About half (47%) of our survey

respondents cited the approval process as one of

their top two challenges in constructing an ADU.

Homeowners shared that they “knew the [C]

ity had to approve the ADU due to new [C]al-

ifornia law, but they threw up pointless rules

and requirements to make it difcult and dis-

couraging,” and that they endured “absolutely

ridiculous red tape, the [C]ounty was no help

in nding solutions.” Statewide, 50% of home-

owners disagreed with the statement that it was

easy to obtain the necessary permits to build their

ADU, with the most positive reviews coming from

San Diego and Orange counties (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Ease of obtaining permits

n= Central Coast: 81, Los Angeles County: 153, San Francisco

Bay Area: 348, Orange and San Diego County: 49

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 10

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation - April 2021

These homeowners struggled with the length and

complexity of the permitting process. Homeown-

ers often felt like their jurisdictions imposed un-

necessary red tape in the permitting process, and

some noted that their architects even struggled

to navigate through the different departments’ re-

quirements. One homeowner outlined their frus-

trations with this process, saying:

Adding to these difculties, some jurisdictions’

ADU programs do not comply with State Leg-

islation, which the State minimally enforces.

One homeowner outlined their experience with

the inconsistencies in regulations and lack of

enforcement:

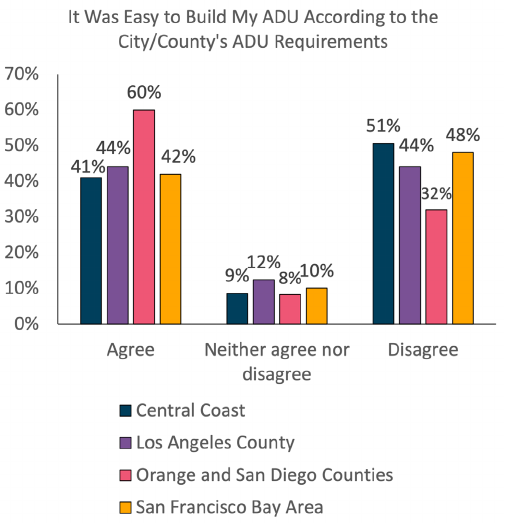

Overall, 50% of homeowners found it difcult to

build their ADUs to their city/county’s develop-

ment standards. These new ADU builders ranked

design constraints (26%), lot setbacks or height

limits (14%), utility connections (14%), and park-

ing requirements (6%) among their top challeng-

es.

8

Notably, homeowners in Orange and San

Diego Counties had the easiest time building

their ADUs according to their jurisdiction’s devel-

opment standards, with 60% of homeowners in

these counties either agreeing or strongly agree-

ing that it was easy to construct their ADU ac-

cording to local regulations, compared to 44% in

Los Angeles County, 42% in the San Francisco

Bay Area, and 41% in the Central Coast (Figure

6).

Figure 6: Ease of following local ADU

regulations

“even though the State passed legis-

lation to standardize the ADU regula-

tions, the City...did not fully adopt [it].

We reached out to the State and they

said they could do nothing to enforce

that the cities follow it. We ended up fol-

lowing the City requirements. Thus, we

were not allowed to convert our garage

into [an] ADU. Instead we built a sepa-

rate attached structure and also built

on-site parking.”

“[m]y bad experience was from the mo-

ment I submitted the plans to the City ...

until they were approved, that single pro-

cess took more than 12 months. It was a

long time wasted, I paid a lot of extra mon-

ey. And a super unpleasant experience.

Next time I better do it regardless of City

permits.”

7

n= Central Coast: 81, Los Angeles County: 153, San Francisco

Bay Area: 348, Orange and San Diego County: 49

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 11

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation - April 2021

Construction Financing

The median construction cost of the ADUs in our

sample was $150,000, or $250/sf. A signicant

portion of ADUs (37%) cost less than $100,000 to

build, and 71% of ADUs cost less than $200,000

to construct (see Appendix B for full cost break-

down). These construction cost gures represent

signicant savings when compared to the state-

wide average construction cost of $480,000 per

unit ($700/sf) for affordable housing units that re-

ceived Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC)

in 2019.

9

However, some of the cost savings as-

sociated with ADUs compared to conventional af-

fordable housing units built using LIHTC funding

may be attributed to the fact that cost of a LIHTC

unit includes land costs, and the cost of an ADU

does not. We found notable cost variation among

the ADUs in our sample based on the region, unit

type, number of bedrooms, type of nancing used

to construct these ADUs, and property owner in-

come (Table 2).

Table 2: Breakdown of median ADU construction costs

Median total construction cost Median construction cost/sf

Region

Central Coast $140,000 $223.04

Los Angeles County $100,000 $197.22

Orange and San Diego Counties $130,000 $200.00

San Francisco Bay Area $177,500 $329.17

ADU unit typology

Detached units $180,000 $300.00

Additions (main residence) $150,000 $250.00

Garage* $90,000 $189.19

Conversion (main residence) $100,000 $173.04

Number of bedrooms in ADU

Studio (0) $100,000 $241.27

1-bedroom

$150,000

$266.67

2-bedrooms $212,500 $250.00

3 or more bedrooms $200,000 $129.17

Financing used to pay for ADU

Cash $150,000 $250.00

Loan(s) from a bank $175,000 $307.69

Money from a friend or relative $185,000 $291.67

Credit card/unsecured debt $100,000 $204.52

Income of property owner

Less than $50,000 $95,000 $176.17

$50,000 - $99,999 $110,000 $200.80

Over $100,000 $170,000 $306.12

*Garage includes garage conversions, and square footage added to existing garages either via vertical or horizontal expansions.

**Financing types are not mutually exclusive

**

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 12

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation - April 2021

A 2020 study by the Terner Center for Housing

Innovation found that “compared to projects in

other parts of the state, Bay Area [housing] proj-

ects cost $81 more per square foot to build.”

10

The cost differential for ADUs appears to be even

greater; the median cost per square foot of an

ADU in the San Francisco Bay Area is $106.13

more expensive than the next most expensive re-

gion. On the other hand, the Terner Center found

that hard construction costs in Los Angeles are

typically $35 more expensive per square foot

than the state average, but we nd that ADUs in

Los Angeles County have a lower median cost

per square foot ($223.04) than the state median

($250).

11

One possible explanation for the lower cost in

Los Angeles County is the region’s reliance on

garage conversions, which accounted for 39% of

total ADUs built (compared to 11-14% in other re-

gions). Garage conversion ADUs, which involve

taking space from, or adding square footage to,

existing garages, are the cheapest to build state-

wide both in terms of overall construction cost and

cost per square foot. Garage conversions may be

cheaper than the typical ADU because homeown-

ers could theoretically use the ADU process to

legalize already converted garage space, though

our survey did not ask homeowners if their ADUs

existed illegally before they applied for an ADU

permit. Our survey also nds that new construc-

tion detached units, while the most popular ADU

type, are also the most expensive to construct.

ADUs with two bedrooms were the most expen-

sive to construct (median cost of $212,500), and

the median price of an ADU with three or more

bedrooms ($200,000) was $50,000 more than a

one-bedroom unit. However, units with more bed-

rooms are cheaper to build per square foot due to

the “sunk costs” associated with ADU construc-

tion, such as architectural fees and the cost of

building a kitchen and bathroom, across all units.

Although ADUs are relatively affordable when

compared to standard housing units in the state,

they still require a signicant amount of capital

to construct. Overall, lower-income homeowners

spent less to construct their ADUs than those with

higher-incomes across the state. Homeowners

who built ADUs using credit cards or unsecured

debt paid much less overall for their units (median

cost of $100,000), as did property owners earn-

ing lower incomes. The types of nancing used

to construct an ADU were fairly consistent across

race and economic status, though our limited

sample size only allowed us to draw conclusions

about Latine and Asian American homeowners.

Prior research shows that there is a demonstra-

ble need for additional nancial mechanisms in

order to spur the development of ADUs state-

wide.

12

The 2019 State Legislature restricted the

types of impact fees that jurisdictions are allowed

to charge for ADUs by prohibiting the collection

of any impact fees for ADU projects less than 750

square feet.

13

One homeowner cited this change

in our ADU survey, saying that:

“the most ‘Positive Aspect’ regard-

ing the developmental process was

when I was informed that, due to

the fact that the State had mandated

and placed restrictions on the per-

mit fee’s [sic] and costs the individ-

ual Cities could charge, I would no

longer be required to sign a Promis-

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 13

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation - April 2021

Still, 158 (24%) of homeowners surveyed cited

paying for the cost of construction as a top chal-

lenge associated with constructing their ADU,

and 32 (5%) struggled to obtain nancing for their

projects. This is signicant since the homeown-

ers in our survey are more afuent than the typi-

cal Californian homeowner.

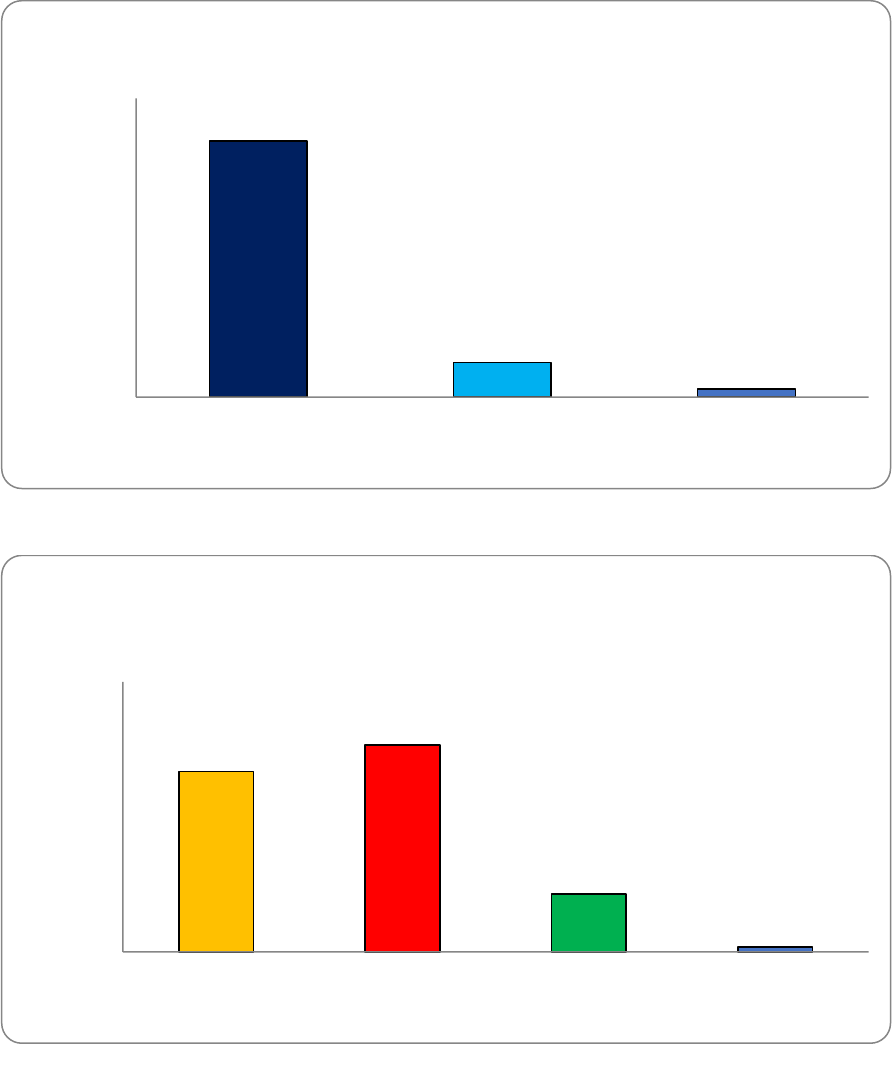

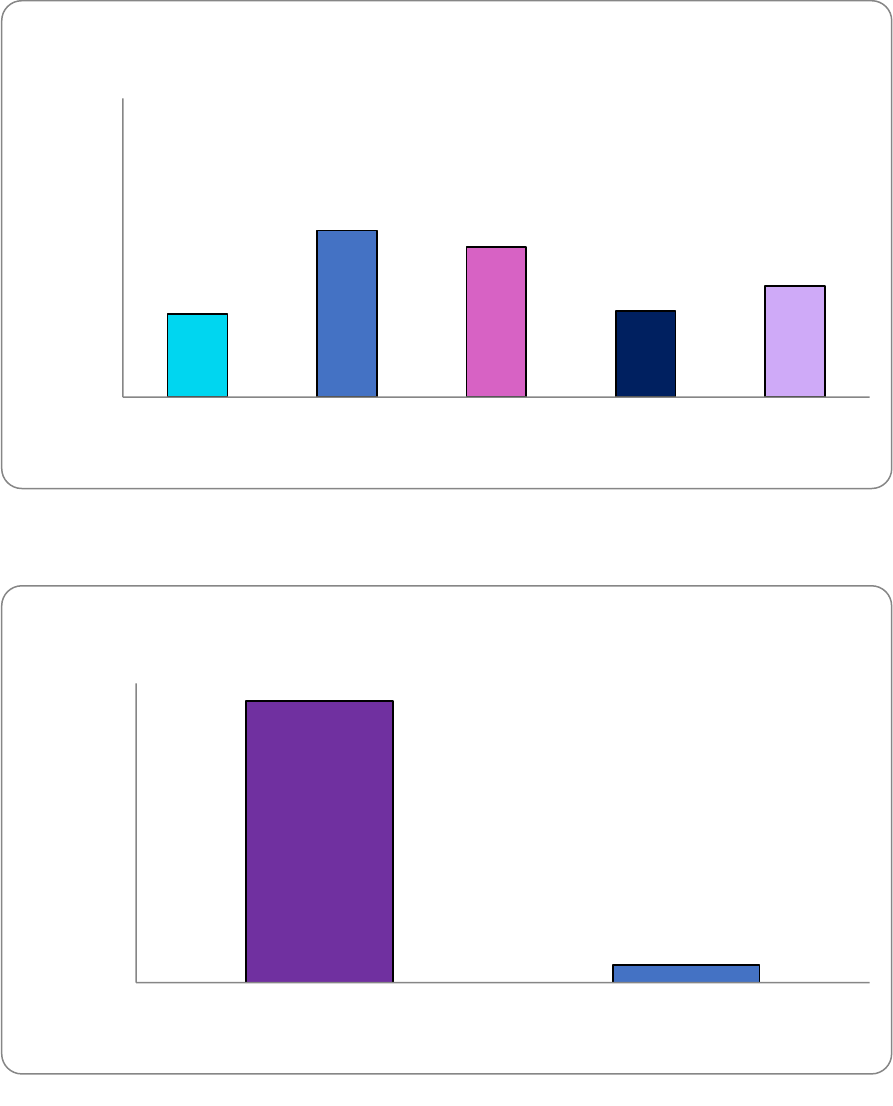

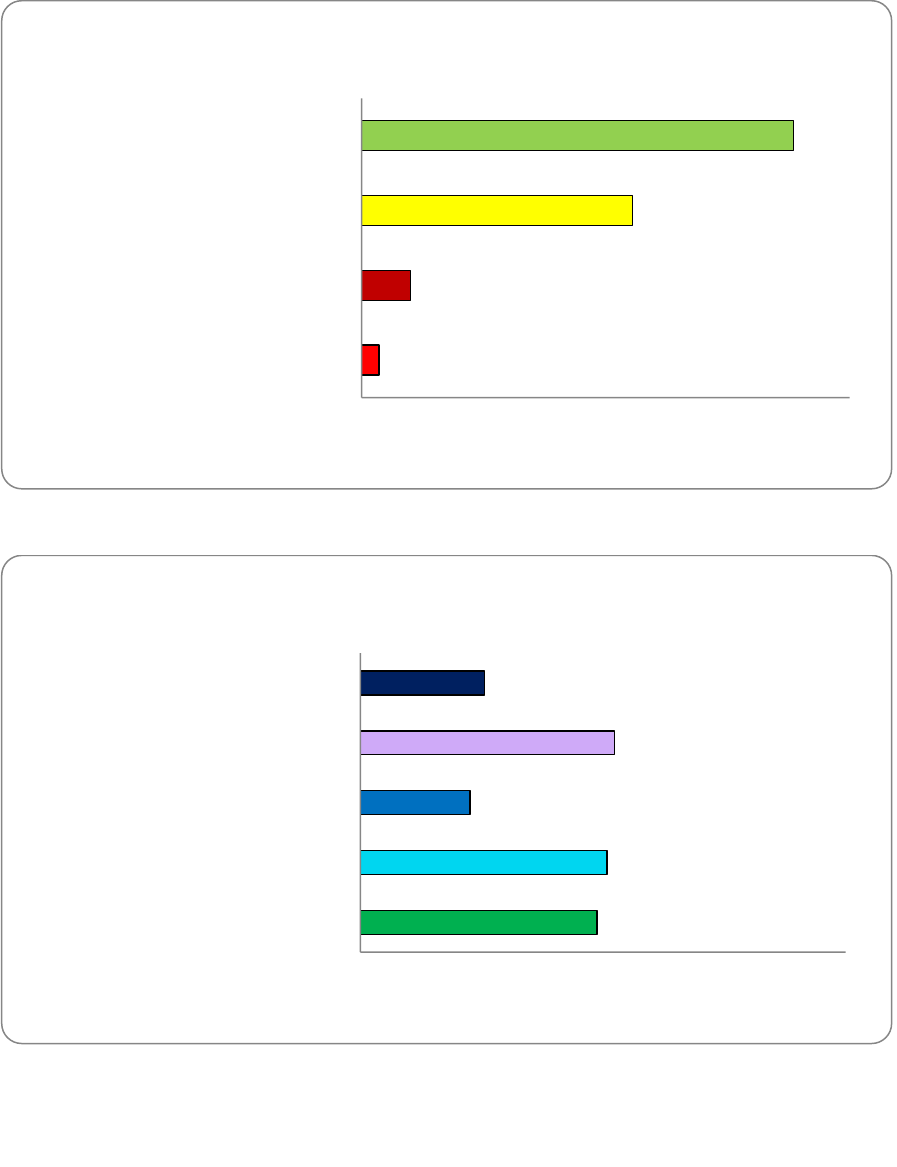

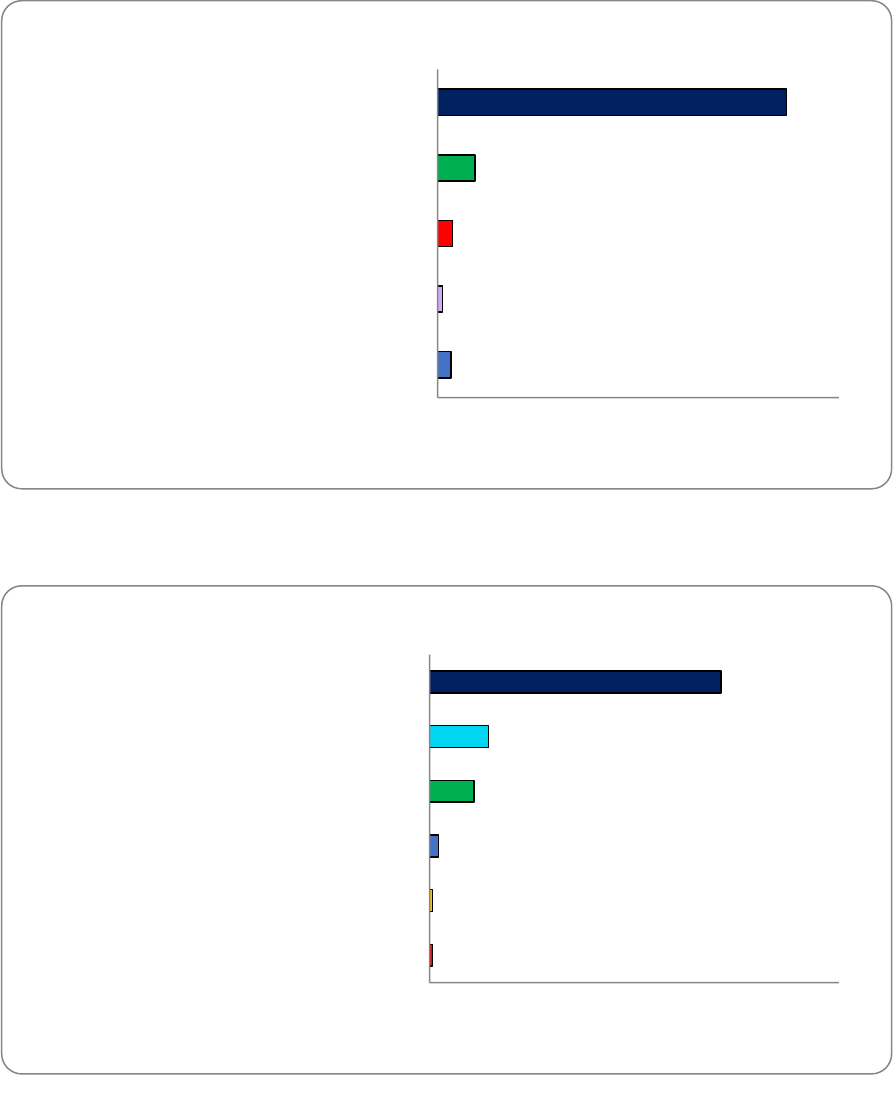

Overall, 62% of homeowners depended wholly or

partially on cash savings, or money from a friend

or a relative, to nance their new ADU (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Financing the construction cost

Of the 43% of homeowners who took out one or

more loans from the bank, 66% used a Home

Equity Line of Credit (HELOC), 41% renanced

their primary residence, 7% obtained a construc-

tion loan from a local lender, and 2% took out a

personal loan from a bank. In an earlier report,

we found that more than half of homeowners who

built an ADU used a conventional loan such as

renancing their primary residence with a cash

out option, 27% relied on a HELOC, and just 1%

used a construction loan.

14

Further research is

necessary to explore these differences, but the

reliance on cash suggests both the lack of nanc-

ing alternatives and the relative afuence of this

set of homeowners.

Construction Process

Homeowners statewide had different experienc-

es navigating the construction process (Figure

8), though almost all (94%) were involved in the

decision-making process about construction de-

cisions for their ADUs.

Figure 8: Navigating the construction process

Notably, the construction experience for home-

owners varied signicantly based on their expe-

rience with contractors: over a hundred of our

survey respondents volunteered that having a

competent contractor was a particularly positive

aspect of their ADU project. One homeowner

noted that “It is absolutely key to nd an ex-

cellent general contractor with veteran sub-

contractors. I don’t think anything is more im-

portant,” and another stated the importance of

sory Note and place a lien on my prop-

erty to satisfy the fee requirements.”

n= 694

*”other” includes instances where respondents rebuilt their pri-

mary residence to include an ADU using insurance money af-

ter a wildre event, equity co-investment programs, owners that

bought the property with an ADU on it, and respondents that se-

lected “other” but did not specify the nancing used.

n= 664

*this may include issues nding a contractor.

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 14

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation - April 2021

“evaluat[ing] and nd[ing] a good construc-

tion company to build the ADU...[to] lessen

the pain and issues during the construction.”

On the other hand, some of our survey respon-

dents were less fortunate, noting that they “were

the victims of fraud and theft” on the part of

their contractors or subcontractors. Despite the

difculties faced during construction, homeown-

ers were still happy with the end result overall.

One homeowner shared that “although the con-

struction was a nightmare, the nished apart-

ment is wonderful and I have had some great

tenants.”

Rental Tenure

Thus far, about half (51%) of California’s new

ADUs serve as income-generating rental units, a

similar proportion to that in our previous Pacic

Northwest survey.

15

Of the ADUs that are rent-

ed out to tenants, only 8% function as short-term

rentals with less than 1 month stays. Property

owners earning $100,000 a year or more were

more likely to use their ADUs as short-term rent-

als (12%) than those earning less than $100,000

a year (7%). Of note, many Californian jurisdic-

tions’ ordinances include language prohibiting

the use of ADUs as short-term rentals.

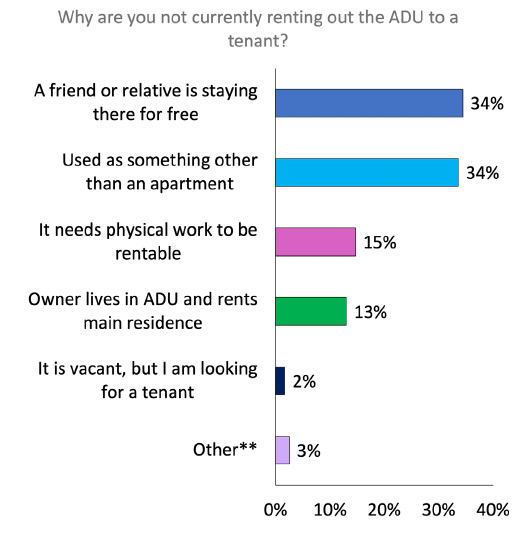

ADUs often serve as affordable housing for

friends or relatives: 18% of the state’s new ADUs

provide no-cost housing for family members

(16%) or friends (2%), again, similar to the pro-

portion found in the previous Pacic Northwest

survey. Approximately 16% of the new ADUs

serve as home ofces, studios, or guest hous-

es for the property owner (Figure 9). This may

be the result of more people working from home

during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the use of

these ADUs may evolve over time as the needs

of the homeowner changes. As one homeown-

er noted, their “original intent was to create a

studio apartment for an aging parent, but it

is now being used as a home ofce (which is

coming in handy during shelter-in-place) and

is also a comfortable guest cottage for family

and friends.”

Figure 9: Reasons not to rent out the ADU*

These new ADUs are typically not family-sized

rental units; in fact, 86% of the state’s renter-oc-

cupied ADUs have just one to two people living

in them. Once again, this echoes the ndings of

n= 366

*includes responses from the 49% of homeowners who reported

that they were not renting out their ADU.

**“other” most commonly includes homeowners not renting their

units out due to concerns about the COVID-19 pandemic, home-

owners not wanting to rent their property out to a random tenant,

and homeowners avoiding renting their units due to concerns

about regulations such as rent control.

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 15

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation - April 2021

the Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver homeowner

survey: 93% of ADUs in those jurisdictions con-

sisted of only one or two person households.

16

Of California’s renter-occupied ADUs, only 11%

have one or more school-aged children (less

than 18 years old) living in them, and only 15%

are occupied by a senior citizen (65+ years old).

The number of people who live in an ADU varies

by the ADU owner’s income. Only 6% of ADUs

owned by property owners earning $100,000 a

year or more are rented to households of three or

more people, compared to 21% of ADUs owned

by property owners that make less than $100,000

a year.

Recent legislative efforts to alleviate parking re-

quirements appear to be effective, as only 6%

of our survey respondents cited parking require-

ments as one of the biggest challenges in con-

structing their ADU.

17

Some jurisdictions and res-

idents have long maintained that the elimination

or waiver of parking requirements would result

in a lack of available street parking in residential

neighborhoods.

18

Of the occupied ADUs in our

sample, 40% of tenants did not park any cars on

the adjacent street, 46% parked one car on the

street, 13% parked two vehicles on the street,

and only 1% parked three or more cars on the

street.

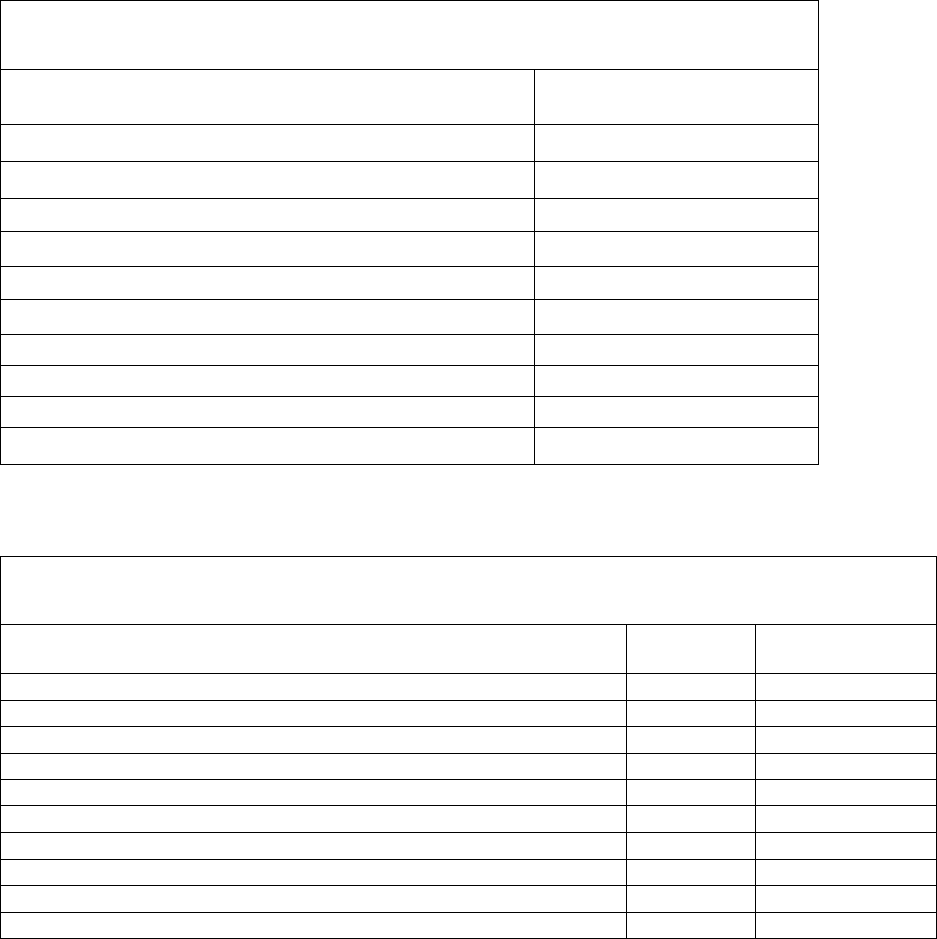

Rental Prices

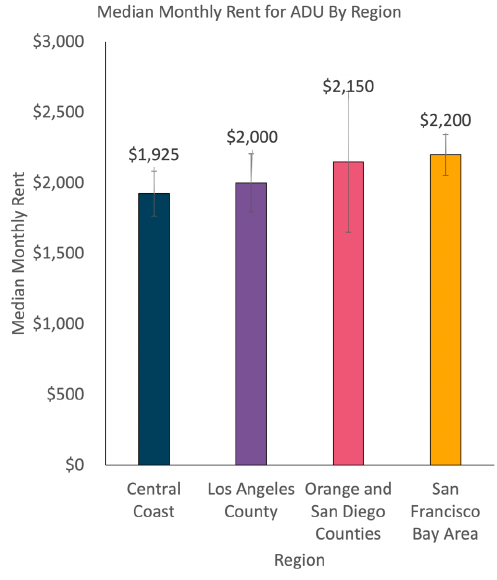

The median rental price of an ADU in California is

$2,000, and the median ADU rent per square foot

in the state is $3.68. Notably, the median rents

varied by region (Figure 10). ADUs in the San

Francisco Bay Area appear to collect the most

both in total rent and in rent per sf, though when

accounting for the margin of error associated

with our dataset, ADUs in Orange and San Diego

County may charge more in total rent. However,

the ADUs in Orange and San Diego County are

also much larger than units in the San Francisco

Bay Area. In terms of median rents per square

foot, ADUs in the San Francisco Bay Area col-

lect the most ($3.94), compared to those in the

Central Coast region ($3.75), Los Angeles Coun-

ty ($3.38), and Orange and San Diego Counties

($3.35).

Figure 10: Median monthly rent by region

The median ADU rental price is affordable (less

than 30% of household income) to a two-per-

son household making the area median income

in the San Francisco Bay Area and the Central

Coast regions.

19

In Orange and San Diego coun-

ties, the large margin of error associated with the

median rental price for an ADU makes it difcult

to make claims about affordability. The median

n= 225

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 16

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation - April 2021

ADU in Los Angeles County rents for $2,000, but

an affordable rent for the median household of

two is $1,546.

19

Approximately 31% of ADUs in

Los Angeles County are affordable to a two-per-

son household making the AMI.

In the counties where we received greater than

20 total survey responses from new ADU land-

lords, we found that a signicant portion of units

are available to those making less than 80% of

the area median income (AMI), though the over-

all affordability varies signicantly by county (Ta-

ble 3). This is fairly consistent with the previous

Pacic Northwest survey, which found that 58%

of ADUs rent for below market rate.

20

There was also modest variation of rents charged

based on the unit type, number of bedrooms in

the ADU, type of nancing used to construct the

ADU, and property owner income (Table 4).

*Income limits sourced from https://www.hcd.ca.gov/grants-funding/income-limits/state-and-federal-income-limits/docs/income-lim-

its-2020.pdf. We base this analysis on a family of two as 86% of ADUs in the state have just 1 or two people living in them.

**n includes all survey respondents that reported charging rent for the unit in a given county.

Table 3: Percent of income-generating rental units available to households making 80% or less

of the area median income by county

Table 4: Breakdown of median ADU rents

*Garage includes garage conversions, and square footage added to existing garages either via vertical or horizontal expansions.

**Financing types are not mutually exclusive.

Median total rent Median rent/sqft

ADU unit type

Detached units $2,200 $3.82

Additions (main residence) $2,000 $3.77

Garage* $1,875 $3.47

Conversion (main residence) $2,200 $3.33

Number of bedrooms in ADU

Studio (0) $1,800 $4.44

1-bedroom $2,000 $3.61

2-bedrooms $2,800 $3.06

3 or more bedrooms $2,800 $2.33

Financing used to pay for ADU

Cash $2,000 $3.73

Loan(s) from a bank $2,100 $3.87

Money from a friend or relative $2,500 $3.77

Credit card/unsecured debt $1,825 $3.54

Income of property owner

Less than $50,000 $1,868 $3.02

$50,000 - $99,999 $1,850 $3.50

$100,000 or more $2,200 $4.00

County

Monthly rent at 80% of AMI

for a family of two*

Percent of units affordable to a family of

two making < 80% of AMI

n**

Alameda $1,907 29% 24

Los Angeles $1,237 12% 51

Marin $2,290 67% 21

Santa Clara $2,266 50% 32

San Mateo $2,290 38% 21

**

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 17

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation - April 2021

Conclusion and Policy

Implications

This survey is the rst statewide effort to

understand the on-the-ground experiences of

homeowners who successfully constructed an

accessory dwelling unit. This report nds that

while ADUs do provide relatively affordable rent-

al housing units for Californians, there are still

signicant barriers to making these a widespread

policy solution for tackling the state’s affordable

housing crisis.

Homeowners with an ADU are more afuent

and less likely to identify as Hispanic or Latine

than the average Californian homeowner. De-

spite the lower construction costs of ADUs when

compared to “conventional” affordable housing

units constructed using Low-Income Housing Tax

Credits, ADUs still require a signicant nancial

investment to build, with the median unit cost-

ing $150,000 ($250/sf). In order to nance these

ADUs, homeowners across all races and eco-

nomic status rely heavily on cash savings.

Financing the construction of an ADU, while a

signicant barrier, is not the only hurdle faced

by homeowners seeking to add an ADU to their

property in California. Homeowners struggle with

proposing ADUs that meet their local planning

department’s requirements, obtaining the neces-

sary permits, and nding an honest and reliable

construction team. Those that successfully con-

structed ADUs noted the benets that these units

provide; for example, creating a source of sup-

plemental rental income or providing multigener-

ational housing.

Moving forward, it is imperative that state and lo-

cal policymakers work to expand access to ADUs

so that all can reap the personal and nancial

benets that these units provide. We recommend

that state and local actors champion the following

initiatives in order to bolster the state’s supply of

ADUs:

Facilitate the construction of ADUs for

lower-income and minority families to

promote equity in housing, provide

benets to marginalized Californians, and

combat the state’s housing affordability cri-

sis.

• We found that lower-income homeown-

ers were more likely to have more tenants

in their ADUs, and were less likely to use

their ADUs as short-term rentals. Promoting

ADUs to low-income Californian homeown-

ers may result in the construction of more

family-sized housing units.

• This can take the form of expanding ADU

nancing options for homeowners, ideal-

ly with terms that are more lenient than a

conventional mortgage or construction loan

in order to allow lower-income Californians

and those with lower credit scores to access

ADU nancing.

• Assembly Bill 561, which was introduced by

Assembly Members Ting and Bloom in Feb-

ruary 2021, is a good rst step toward ac-

complishing this. AB 561 would require the

State Treasurer to develop a “Help Home-

owners Add New Housing Program” with the

stated purpose of assisting homeowners in

qualifying for loans to build an ADU.

21

This

legislation replicates the efforts of the 2018

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 18

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation - April 2021

Assembly Bill 69, which the State Legisla-

ture approved but Governor Newsom ve-

toed in September 2020.

Fund and require state-level review of

local ADU regulations to ensure that the

regulations, and the interpretation of those

regulations, are in compliance with all

relevant state-level legislation.

• Although local jurisdictions are currently

required to submit their adopted ADU or-

dinances to the California Department of

Housing and Community Development,

HCD currently does not enforce State Leg-

islation or penalize jurisdictions for ADU re-

quirements that are out of compliance with

State Law.

• Governor Gavin Newsom’s proposed 2021-

2021 budget includes resources to create a

Housing Accountability Unit within HCD that

would be tasked with monitoring and enforc-

ing state housing legislation, as well as funds

for HCD to increase technical assistance to

help jurisdictions implement state housing

legislation.

22

The creation of this Housing

Accountability Unit is a necessary step to-

wards ensuring that jurisdictions act in good

faith when developing ADU programs, and

increasing the viability of ADUs statewide.

Make local permitting processes more

user-friendly, and better assist

inexperienced homeowners with obtaining lo-

cal approvals to build an ADU.

• This can include creating a dedicated ADU

website with accurate information, dedicat-

ing city staffers as ADU specialists to an-

swer any technical questions, and offering

pre-approved ADU plans. These efforts will

help to remove barriers associated with per-

mitting and local approvals.

• Ensure that all ADU outreach materials are

accessible in multiple languages to increase

ADU production in minority communities,

particularly among the Hispanic and Latine

communities.

• Jurisdictions should also make all relevant

ADU requirements, not just the requirements

of planning departments, easily accessible

to homeowners seeking to build an ADU in

order to mitigate “surprise” regulations and

fees as plans for an ADU move through the

local permitting process.

• Introducing local amnesty ADU programs,

or unit legalization programs, can also help

bring informal in-law units into California’s

legal housing supply while ensuring that

these existing units meet all relevant health

and safety codes.

Facilitate a smoother construction process

for homeowners.

• The construction process can be a lengthy

and emotional process for homeowners

as they invest their own time and mon-

ey in a construction process that takes

place on their property. Jurisdictions and

nonprot organizations can help improve

this process by providing digital resourc-

es on navigating the construction process,

matching homeowners with experienced

contractors, and providing project manage-

ment services or support groups to home-

owners going through the ADU process.

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 19

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation - April 2021

While our research provides the most compre-

hensive look to date at physical and economic

characteristics of ADUs constructed throughout

the state, our data has limitations. Our sample of

homeowners only included those who built ADUs

in 2018 and 2019. Importantly, the 2019 state-lev-

el ADU Legislation, which became effective on

January 1, 2020, may have addressed or mitigat-

ed some of the pain points associated with con-

structing an ADU that this survey identies. Ad-

ditionally, our survey sample over-represents the

San Francisco Bay Area and under-represents

Los Angeles County. Future surveys should con-

tinue to monitor the extent to which new ADUs

alleviate the affordability crisis in California.

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 20

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation - April 2021

Endnotes and Works Cited

1. Chapple, K., Garcia, D., Tucker, J., & Valchuis, E. (2020, December 10). Reaching California’s ADU Potential: Progress to Date and

the Need for ADU Finance. Retrieved from https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/research-and-policy/reaching-californias-adu-po

tential-progress-to-date-and-the-need-for-adu-nance/

2. Cities that provided supplemental ADU addresses include: Belmont, Brisbane, Burlingame, Cloverdale, Corte Madera, Cupertino,

Foster City, Half Moon Bay, Healdsburg, Keneld, Lagunitas, Larkspur, Marin County, Mill Valley, Milpitas, Mountain View,

Novato, Pacica, Palo Alto, Redwood City, San Anselmo, San Bruno, San Jose, San Mateo, San Rafael, Saratoga, Sunnyvale

& Tiburon.

3. U.S. Census Bureau. 2019 American Community Survey 1-year Income in the Past 12 Months (in 2019 Ination-Adjusted Dollars).

4. Chapple, K., Lieberworth, A., Hernandez, E., Ganetsos, D., Alvarado, A., & Morgan, J. (2020, February 1). The ADU Scorecard -

ADU California. Retrieved from https://www.aducalifornia.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/ADU-Scorecard-InterimRe

port-200201-1.pdf

5. Assembly Bill (AB) 68, passed by the State Legislature in 2019, seeks to limit the use of zoning tools to restrict lot size by requir-

ing all jurisdictions to permit “at least an 800 square foot accessory dwelling unit that is at least 16 feet in height with 4-foot side and

rear yard setbacks to be constructed. This bill would additionally prohibit the imposition of limits on lot coverage, oor area ratio, open

space, and minimum lot size if they prohibit the construction of an accessory dwelling unit meeting those specications.” (AB 881,

Bloom)

6. Chapple, K., Wegmann, J., Mashhood, F., & Coleman, R. (2017, July). JUMPSTARTING THE MARKET FOR ACCESSORY DWELL

ING UNITS. Retrieved from https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/Jumpstarting_the_Market_--_ULI.pdf

7. Original Spanish text: “ [m]i mala experiencia fue desde el momento que sometí los planos a la ciudad...hasta que me los aproba-

on, se tardaron más de 12 meses ese sólo proceso. Fue mucho tiempo perdido, pague mucho dinero extra. Y una experiencia súper

desagradable. La próxima vez mejor lo hago sin tomar en cuenta permisos de la ciudad.”

8. State-level ADU legislation passed in 2019 (Assembly Bill (AB) 68, AB 881, and Senate Bill (SB) 13, reduced the scope of regulation

that localities could impose around lot setbacks, height limits, and parking requirements for ADU projects. As such, these difculties

may no longer be an issue for homeowners seeking to add an ADU to their property today.

9. Reid, C. (2020, December 22). The Costs of Affordable Housing Production: Insights from California’s 9% Low-Income Housing Tax

Credit Program. Retrieved from https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/research-and-policy/development-costs-lihtc-9-percent-cali

fornia/

10. Raetz, H., Kneebone, E., Reid, C., & Forscher, T. (2020, December 22). The Hard Costs of Construction: Recent Trends in Labor

and Materials Costs for Apartment Buildings in California. Retrieved from https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/research-and-poli

cy/hard-construction-costs-apartments-california/

11. Raetz, Kneebone, Reid, & Forscher, 2020.

12. Chapple, Garcia, Tucker, & Valchuis, 2020.

13. SB13, Wieckowski. Accessory dwelling units, 2019 Reg. Sess. (CA 2019). https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.

xhtml?bill_id=201920200SB13

14. Chapple, K., Lieberworth, A., Ganetsos, D., Valchuis, E., Kang, A., & Schten, R. (2020, October). ADUs in CA: A Revolution in Prog

ress. Retrieved from https://www.aducalifornia.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/ADU-Progress-in-California-Report-Octo

ber-Version.pdf

15. Chapple, Wegmann, Mashhood, & Coleman, 2017.

16. Chapple, Wegmann, Mashhood, & Coleman, 2017.

17. In the 2019 legislative session, the State mandated that no replacement parking spaces may be required if a garage, carport, or

covered parking space is demolished or converted to create an ADU. In addition, the state strengthened its existing requirements for

jurisdictions to provide certain exemptions from local parking requirements depending on the characteristic and location of the ADU and

the subject property in the same legislative session.

AB 881, Bloom. Accessory dwelling units, 2019 Reg. Sess. (CA 2019). AB 68, Ting. Land use: accessory dwelling units, 2019 Reg.

Sess. (CA 2019). https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200AB881 https://leginfo.legisla

ture.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200AB68

18. Chapple et al. 2012 (Yes in My Backyard)

19. Affordable monthly rents for a family of two earning 100% of the area median income per HUD, based on counties in the region:

• Central Coast ($1,633 - $2,200)

• Los Angeles County ($1,546)

• Orange and San Diego Counties ($1,853 - $2,060)

San Francisco Bay Area ($1,908 - $2,862)

Calculated by taking the high and low values of 30% of the HUD provided 2020 household area median incomes (https://www.hcd.

ca.gov/grants-funding/income-limits/state-and-federal-income-limits/docs/income-limits-2020.pdf) for each county in a given region, and

then dividing by 12 to reect a monthly rental price.

20. Chapple, Wegmann, Mashhood, & Coleman, 2017.

21. AB 561, Ting. Help Homeowners Add New Housing Program: accessory dwelling unit nancing,

2021 Reg. Sess. (CA 2021). https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_

id=202120220AB561

22. California Budget 2021-22. (2021, January). Retrieved from http://www.ebudget.ca.gov/

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 21

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation - April 2021

Appendix A: Full Survey Text

1. Are you the owner of the property/ADU?

(Yes, No)

2. How many Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) are on your property? ADUs can take different forms,

including a rst oor or basement that has been converted to a unit, a freestanding backyard cot-

tage, a garage that has been turned into an apartment, and others. ADUs are often rented out to

tenants.

(1, 2, 3, 4 or more)

3. What stage of construction is your ADU in?

(Completed, Under Construction, Not Yet Under Construction, Other (Please Specify))

4. Is the ADU a rental property at any time?

(Yes, I rent to a tenant that I did not know previously; Yes, I rent to a family member/acquaintance;

No)

5. What type of rental property is your ADU?

(Short-term rental (less than 1 month stay), Long-term rental)

6. How many people live in the ADU?

(0, 1, 2, 3, 4 or more)

7. Of those living in the ADU, are there any school-aged children (18 & under) living there?

(Yes, only one; Yes, more than one; No)

8. Of those living in the ADU, are there any senior citizens (65+) living there?

(Yes, only one; Yes, more than one; No)

9. On average, how much do you charge in rent per month? (Number only please: E.g. 1500)

(Total monthly rent: ____, Tenant portion of utilities: _____)

10. Why are you not currently renting out the ADU to a tenant?

(It needs physical work to be rentable; A friend is staying there for free; A relative is staying there

for free; It is vacant, but I am looking for a tenant; It is being used as something other than an

apartment (home ofce, workshop, studio, etc); Other (Please Specify))

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 22

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation - April 2021

11. Do you receive any services from the ADU occupant(s) in exchange for all or part of the rent (e.g.

childcare, lawn maintenance, etc.)?

(Yes (Please Specify), No)

12. How would you best describe the physical layout of your ADU?

(Detached (free standing building), Attached (connected to the the main house, but built as an ad-

dition), Garage or other building conversion, Basement/attic or other room in the house converted

to ADU, Other (Please Specify))

13. How many bedrooms are in the ADU?

(0, 1, 2, 3, 4 or more)

14. What is the approximate square footage of your ADU? (Numbers only: E.g. 600)

(______)

15. Did you own the property when the ADU was built?

(Yes, No)

16. How much did you or someone else pay for your ADU to be constructed? Please include the costs

for design, labor, materials, and permits. Your best estimate is ne. (Numbers only: E.g. 5000). If

you do not know, enter 0.

(______)

17. How did you nance the construction cost? (Check all that apply)

(Cash, Credit Card/Unsecured Debt, Money from friend or relative, Loan from bank, Other (Please

Specify))

18. What kind of loan did you take out? (select all that apply)

(Home Equity Line of Credit, Renancing, Construction loan, Other (Please Specify))

19. Were you involved in the decision-making about ADU construction?

(Yes, No)

20. What were the two biggest challenges you faced in building your ADU? Check up to two.

(Obtaining nancing, Paying for the cost of construction, Permitting fees, Lot setbacks or height

limits, Utility connections, Parking requirements, Design constraints or challenges, Approval pro-

cess, Don’t know, Other (Please Specify))

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 23

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation - April 2021

21. What was the factor that was most helpful in making it possible for you to build?

(Fee Waivers; Relaxing the requirement that the owner must live on the property; Neighbor built

one; Educational website, event, advertisement; Cash Availability; Zoning Reforms; Policy Re-

form: (Please name specic policies); Other (Please Specify))

22. From the beginning of the approval process start to completion of the ADU, how many months did

it take? Please select the total number of months (E.g. 14 for one year and two months)

(______)

23. It was easy to obtain the necessary permits to build my ADU. (This may include zoning counter

issues, level of transparency of requirements, duration of permitting timelines, number of plan

revisions required, and code changes impacting design mid-city review.)

(Strongly disagree, Somewhat disagree, Neither agree nor disagree, Somewhat agree, Strongly

agree)

24. It was easy to build my ADU according to the city/county’s ADU development requirements. (This

may include local requirements for ADU height, side/rear setbacks, parking, and the zones where

ADUs are allowed.)

(Strongly disagree, Somewhat disagree, Neither agree nor disagree, Somewhat agree, Strongly

agree)

25. It was easy to navigate the construction process for my ADU. (This may include issues nding a

contractor.)

(Strongly disagree, Somewhat disagree, Neither agree nor disagree, Somewhat agree, Strongly

agree)

26. It was easy to pay for my ADU. (This may include cost of construction, permitting fees, number or

diversity of nancing options, and cost of design professionals.)

(Strongly disagree, Somewhat disagree, Neither agree nor disagree, Somewhat agree, Strongly

agree)

27. Who did the physical construction on your ADU? (Select all that apply)

(A paid contractor, Myself or another owner of the property, A paid friend or relatives, Other

(Please Specify))

28. Please describe any particularly positive aspects about the process to construct your ADU.

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 24

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation - April 2021

29. How many total cars do your tenants living in the ADU normally park on the street? If you don’t

have any tenants, choose “I don’t have any tenants living in the ADU.”

(None, 1, 2, 3 or more, I don’t have any tenants living in the ADU)

30. What was your household’s before-tax income in the last 12 months? Please include all income,

including salaries, wages, investments, government benets, etc. Please do not include people

living in the ADU (if any) as members of your household for the purposes of this question.

(Less than $10,000, $10,000 to $14,999, $15,000 to 24,999, $25,000 to $34,999, $35,000 to

$49,999, $50,000 to $74,999, $75,000 to $99,999, $100,000 to $149,999, $150,000 to $199,999,

$200,000 or more)

31. Are you of Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin?

(No, not of Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin; Yes, Mexican, Mexican-American, Chicano; Yes,

Central American; Yes, other Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin (Please specify); Undisclosed)

32. How would you best describe yourself?

(American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other

Pacic Islander, White, Undisclosed)

33. While we tried to be comprehensive in selecting the questions to include in this survey, there sure-

ly are issues that we have not considered. If there is anything else about your experience building

an ADU that you would like to tell us about, if so please write it below.

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation – April 2021

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 25

Appendix B – Summary of All Survey Findings

n=746

*ADUs can take different forms, including a first floor or basement that has been converted to a unit, a

freestanding backyard cottage, a garage that has been turned into an apartment, and others. ADUs are often

rented out to tenants.

n=724

53%

23%

13%

9%

2%

0% 20% 40% 60%

Detached (free standing building)

Garage or other building conversion

Attached (connected to the the main

house, but built as an addition)

Basement/attic or other room in the

house converted to ADU

Other

Physical Layout of ADU

How would you best describe the physical layout of

your ADU?

97%

2%

0.5% 0.5%

0%

50%

100%

1 2 3 4 or more

Number of ADUs

How many Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) are on

your property?*

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation – April 2021

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 26

n=724

n=709

18%

61%

18%

3%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

0 1 2 3 or more

Number of Bedrooms in ADU

How many bedrooms are in the ADU?

23%

50%

20%

7%

0%

20%

40%

60%

100 to 400 401 to 700 701 to 1000 1001+

Approximate Square Footage of ADU

What is the approximate square footage of your ADU?

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation – April 2021

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 27

n=721

n=747

92%

8%

0%

50%

100%

Yes No

Did you own the property when the ADU was built?

49%

32%

19%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

No Yes, I rent to a tenant that I

did not know previously

Yes, I rent to a family

member/acquaintance

Is the ADU a rental property at any time?

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation – April 2021

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 28

n=366

*includes responses from the 49% of homeowners who reported that they were not renting out their ADU.

**“other” most commonly includes homeowners not renting their units out due to concerns about the COVID-19

pandemic, homeowners not wanting to rent their property out to a random tenant, and homeowners avoiding renting

their units due to concerns about regulations such as rent control.

n=380

34%

34%

15%

13%

2%

3%

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50%

A friend or relative is staying there

for free

Used as something other than an

apartment

It needs physical work to be rentable

Owner lives in ADU and rents main

residence

It is vacant, but I am looking for a

tenant

Other**

Why are you not currently renting out the ADU to a

tenant?*

92%

8%

0%

50%

100%

Long-term rental Short-term rental (less than 1

month stays)

Type of Rental Property

What type of rental property is your ADU?

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation – April 2021

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 29

n=381

n=370

2%

51%

35%

7%

5%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

0 1 2 3 4 or more

Number of People

How many people live in the ADU?

89%

8%

3%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

No Yes, only one Yes, more than one

Of those living in the ADU, are there any school-aged

children (18 & under) living there?

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation – April 2021

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 30

n=370

n=481

86%

12%

3%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

No Yes, only one Yes, more than one

Of those living in the ADU, are there any senior

citizens (65+) living there?

40%

46%

13%

1%

0%

20%

40%

60%

None 1 2 3 or more

Total Number of Cars

For those with tenants currently living in the ADU, how

many total cars do your tenants living in the ADU

normally park on the street?

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation – April 2021

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 31

n=209

*Note, only includes respondents who have paying tenants

n=100

7%

21%

33%

18%

9%

11%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

$700-1,200

$1,201-1,700

$1,701-2,200

$2,201-2,700

$2,701-3,200

$3,201+

Monthly Rent

On average, how much do you charge in rent per

month?

53%

38%

5%

4%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

$1-$100 $101-$200 $201-$300 $301+

Tenant Monthly Utilities Payment

On average, how much do your tenants pay in utilities

every month?

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation – April 2021

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 32

n=478

n=752

89%

4%

3%

4%

11%

Do you receive any services from the ADU

occupant(s) in exchange for all or part of the rent (e.g.

childcare, lawn maintenance, etc.)?

No

Yes - Childcare

Yes -

Maitenance/Gardening/H

ousework

Yes - Other

88.0%

8.0%

3.6%

0.3%

0.1%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

Complete Under

Construction

Not yet under

construction

Project

discontinued

Other

Stage of Construction

What stage of construction is your ADU in?

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation – April 2021

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 33

n=660

n=721

14%

28%

25%

14%

19%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

1 to 5 6 to 10 11 to 15 16 to 20 21 to 25

Number of Months

From the beginning of the approval process start to

completion of the ADU, how many months did it take?

94%

6%

0%

50%

100%

Yes No

Were you involved in the decision-making about ADU

construction?

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation – April 2021

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 34

What were the two biggest challenges you faced in building

your ADU?

Challenge

Occurrence (Total)

Approval process

311

Design constraints or challenges

176

Paying for the cost of construction

158

Permitting fees

118

Lot, setback, or height limits

120

Utility connections

90

Parking requirements

37

Obtaining financing

32

None

9

Other

32

What was the factor that was most helpful in making it possible for you to

build?

Factor

Occurrence

(%)

Occurrence

(Total)

Zoning Reforms

28%

181

Cash Availability

22%

141

Other: Please Specify

18%

116

Policy Reform

17%

110

None

4%

27

Relaxing the requirement that the owner must live on the property

4%

25

Educational website, event, advertisement

4%

23

Fee Waivers

3%

22

Neighbor built one

1%

9

Total

100%

654

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation – April 2021

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 35

n=674

*select all that apply

n=664

* This may include issues finding a contractor

17

39

48

71

491

0 100 200 300 400 500

A paid friend or relative

Other

Myself or another owner of the

property

Multiple

A paid contractor

Who did the physical construction on your ADU?

16%

30%

18%

20%

16%

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50%

Strongly agree

Somewhat agree

Neither agree nor disagree

Somewhat disagree

Strongly disagree

It was easy to navigate the construction process for

my ADU*

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation – April 2021

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 36

n=623

*Please include the costs for design, labor, materials, and permits. Your best estimate is fine.

37%

34%

16%

8%

5%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

$50,000 to

$100,000

$100,001 to

$200,000

$200,001 to

$300,000

$300,001 to

$400,000

$400,001+

Amount Paid for ADU Construction

How much did you or someone else pay for your ADU

to be constructed?*

363

269

68

63

46

6

3

0 100 200 300 400

Cash

Loan from bank

Money from friend or relative

Other

Credit Card/Unsecured Debt

401K/IRA Early Withdrawal

Government Loans

Financing Source

How did you finance the construction cost? (Check all

that apply)

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation – April 2021

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 37

n=665

* This may include cost of construction, permitting fees, number or diversity of financing options,

and cost of design professionals.

n=694

15%

25%

24%

24%

13%

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50%

Strongly agree

Somewhat agree

Neither agree nor disagree

Somewhat disagree

Strongly disagree

It was easy to pay for my ADU*

52%

43%

10%

7%

1%

1%

1%

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

Cash

Loan from bank

Money from friend or relative

Credit Card/Unsecured Debt

401K/IRA Early Withdrawal

Government Loans

Other*

Financing Source

How did you finance the construction cost? (Check all

that apply)

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation – April 2021

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 38

n=665

* This may include zoning counter issues, level of transparency of requirements, duration of

permitting timelines, number of plan revisions required, and code changes impacting design

mid-city review

177

111

20

7

0 50 100 150 200

Home Equity Line of Credit

Refinancing

Construction loan

Personal loan

Loan Type

What kind of loan did you take out? (select all that

apply)

13%

26%

11%

25%

25%

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50%

Strongly agree

Somewhat agree

Neither agree nor disagree

Somewhat disagree

Strongly disagree

It was easy to obtain the necessary permits to build my

ADU*

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation – April 2021

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 39

n=667

* This may include local requirements for ADU height, side/rear setbacks, parking, and the

zones where ADUs are allowed

n=695

* Please include all income, including salaries, wages, investments, government benefits, etc.

Please do not include people living in the ADU (if any) as members of your household for the

purposes of this question.

13%

31%

10%

28%

18%

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50%

Strongly agree

Somewhat agree

Neither agree nor disagree

Somewhat disagree

Strongly disagree

It was easy to build my ADU according to the

city/county’s ADU development requirements*

9%

21%

20%

17%

33%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

Less than

$50,000

$50,000 to

$99,999

$100,000 to

$149,999

$150,000 to

$199,999

$200,000 or

more

Before-tax Income

What was your household’s before-tax income in the

last 12 months?*

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation – April 2021

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 40

n=698

n=695

83%

9%

4%

1%

3%

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

No, not of Hispanic, Latino or

Spanish origin

Yes, Mexican, Mexican-American,

Chicano

Yes, other Hispanic, Latino or

Spanish origin

Yes, Central American

Undisclosed

Are you of Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin?

71%

14%

11%

2%

1%

1%

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

White

Asian

Undisclosed

Black or African American

American Indian or Alaska Native

Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific

Islander

How would you best describe yourself?

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 41

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation - April 2021

Appendix C: Detailed Methodology

Survey Population

In order to collect information from homeowners with an ADU on their property, we developed and

administered a digital survey in both English and Spanish (see Appendix A for full survey text, and

Appendix B for high-level survey results). We used the California Department of Housing and Com-

munity Development’s (HCD) Annual Progress Report (APR) database of properties that applied for

an ADU permit or received a Certicate of Occupancy for an ADU in the year 2018 or 2019 to identify

our survey recipients. We supplemented our APR database with a list of ADUs completed in certain

Bay Area jurisdictions provided by a private planning rm. The jurisdictions that provided supplemen-

tal ADU addresses include: Belmont, Brisbane, Burlingame, Cloverdale, Corte Madera, Cupertino,

Foster City, Half Moon Bay, Healdsburg, Keneld, Lagunitas, Larkspur, Marin County, Mill Valley, Mil-

pitas, Mountain View, Novato, Pacica, Palo Alto, Redwood City, San Anselmo, San Bruno, San Jose,

San Mateo, San Rafael, Saratoga, Sunnyvale & Tiburon.

Postcards

Based on our population of ADU projects, we sent out three rounds of English-language postcards

to 15,745 addresses on August 31, 2020, September 8, 2020, and October 5, 2020 inviting property

owners to take our online survey. We also distributed a fourth round of Spanish-language postcards

on November 11, 2020 to 4,367 addresses in our database located in the top quartile of Spanish

speaking census tracts in the state, where 57.1% or more of the households reported being Spanish

speaking. Each postcard contained a unique survey URL and a scannable QR code that directed

the postcard recipient to our digital survey. The recipients of the Spanish postcards had the option

to complete our survey in either English or Spanish. We incentivized our postcard recipients to com-

plete our survey by offering the chance to win one of three gift cards valued at $450, $250, and $100

respectively to one of the following retailers: Home Depot, Amazon, Apple Store, or Nike. The winners

were selected via random lottery.

Notably, our postcard distribution efforts in late summer and early fall coincided with the 2020 pan-

demic and elections, so it is possible that our low response rate may be attributed to our postcard

getting lost in the large volume of mailers and yers that typically accompany an election season.

Response Bias

Importantly, our survey respondents are not representative of the universe of ADU owners in Califor-

nia. Despite our efforts to distribute postcards to most properties that either completed an ADU proj-

ect or applied for an ADU permit in 2018 or 2019, the distribution of counties among those who took

our survey is different than the distribution of counties in the ADU population. For example, jurisdic-

Implementing the Backyard Revolution 42

UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation - April 2021